It is a dark irony of my life as an artist living in New York City that going to museums ends up seeming at worst like a job or at best like playing hooky. The holiday season does not lighten my workload–rather it adds to it, it is catching-up-with-paperwork time. Nevertheless I’ve been intent on also systematically catching up with as many of the museum shows that have opened over the past months as I can and have already had some wonderful experiences.

I’ll focus first on the shows that are closing in the next few days so that readers in New York might be reminded and encouraged to see them in this New Year.

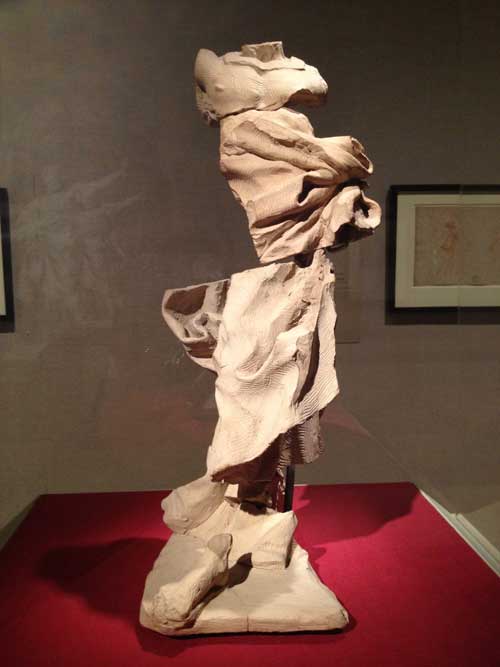

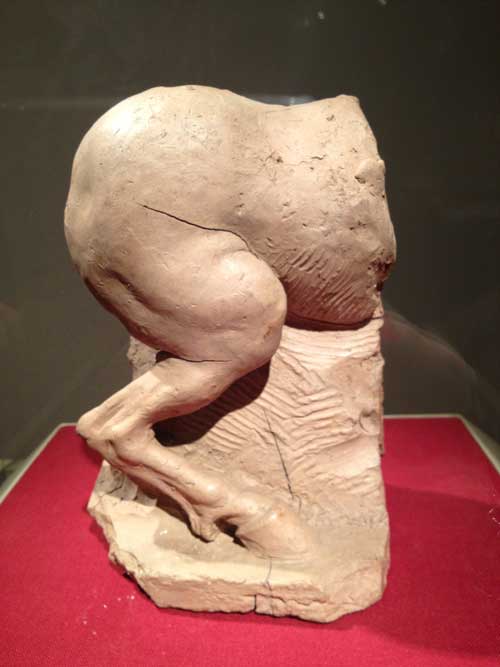

Tucked away in the lower level of the Lehman collection at the Metropolitan, is the wonderful show Bernini: Sculpting in Clay. Bernini worked on small quick studies in fired terracotta for sculptures later to be carved in marble. Sometimes, in these small figures, he’s just trying to figure out the placement of a joint in a fragmentary sculpture of a horse’s rear, or the fall of drapery on a moving figure, sometimes he develops a sketch of the full figure. Quick, expressionistic, fragmentary, marked by sharp engraved and incised lines from special tools, the figures step outside of their historical time: excepting perhaps some details of the faces, these could well have been found in the studio of Rodin or de Kooning.

The show is small but there are a lot of works, beautifully installed and there’s interesting educational material. I was almost as inspired by the illustrated description of the techniques used to create the clay mass Bernini carved into as by the sculptures themselves: the care that went into rolling and packing a clay mass so that it would have no air bubbles that might shatter a piece in the firing process and the combination of the vivid figures and the prospect of such an infinitely malleable, richly colored, and durable material makes you want to make sculpture in that medium. There’s also an animated Renaissance map of Rome highlighting all of Bernini’s public commissions, for which many of the small sculptures are studies, which is immensely impressive as to one single artist’s contribution to the enduring life of a city and the care that went into every expressive detail. Today the equivalent planning for such public commissions would most likely be done on a computer. What a pity. The show is open though January 6. I highly recommend it.

On another day in December, I thought I’d see the Picasso show at the Guggenheim but stopped first at the National Academy to see Her Own Style: An Artist’s Eye With Judith Shea. Invited to curate a show from the collection of the National Academy, sculptor and Academician Judith Shea decided to focus on the self-portraits and in some case portraits by other women artists of women members of the Academy. This is a very carefully crafted, lovingly researched, highly absorbing exhibition, not at all flashy but there are some very interesting and evocative works, among these Shea’s own figurative sculptures. The show sort of sneaks up on you and viewing is enriched by a video which runs in one of the upstairs rooms of the exhibition (you also watch Shea’s informative interview on NYCArts). Shea’s carefully researched comments about each artist opens a view on serious careers and interesting lives of women artists known, such as Alice Neel, and in many cases obscure, or at least many of which I for one was not aware, artists such as Ellen Emmet Rand (1876-1941), who painted three portrait of F.D.R. including his official White House portrait and who I think Shea explained made $75,000 a year from her work during the Depression, a huge sum of money. Rand depicts herself in a loose smock, wearing glasses and a hat, in the act of painting, holding a palette and brushes, as Shea notes, by “minimizing her femininity as a way of maximizing her professionialism.” The women artists’ self-image range from the artist as society beauty (Cecilia Beaux, 1894) to blunt presentation of the woman artist as worker (Louisa Matthiasdottir, c.1985). I was particularly struck with a haunting 1954 self-portrait of Marion Greenwood (1909-1970), a blue gray painting of the artist smoking a cigarette, an expressive painterly surface with one spot of red paint under her right eye.

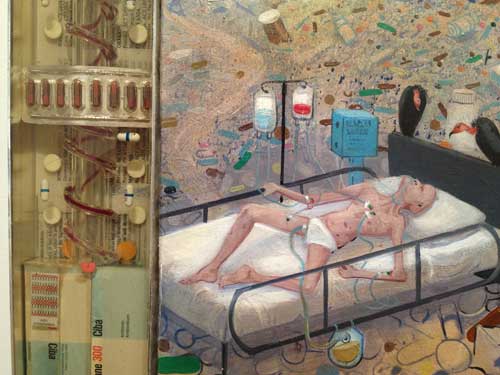

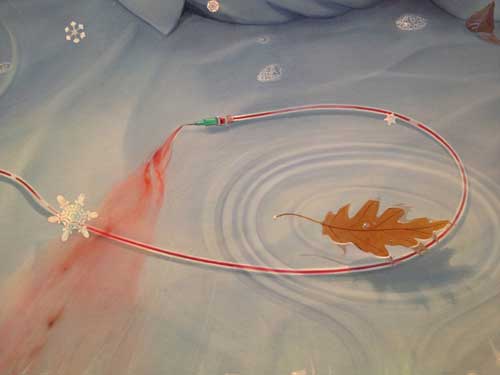

Four of Shea’s own, life size, figurative sculptures, a bronze downstairs, and three other mixed media works grouped in an oval room upstairs are a highlight of the exhibition: these depict Louise Bourgeois, Elizabeth Catlett, and a self-portrait by Shea. Each piece is exquisitely crafted, with an unusual mix of materials, carved and painted wood, clay, foam, paint, each robbed in a warm felt dress. These are figures of great dignity and calm. They are hard and soft at the same time, have the allure of a clothes mannequin, and the calm authority of a classic Kouros figure. Shea is a very interesting artist and here also an intelligent and generous curator.

Judith Shea, Elizabeth Tribute: Portrait of Elizabeth Catlett, 2012. Wood, clay, foam, felt, paint, other, 72x21x21 inches

This show closes runs through January 13, I highly recommend it.

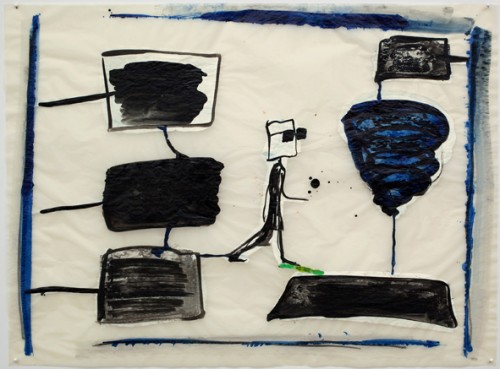

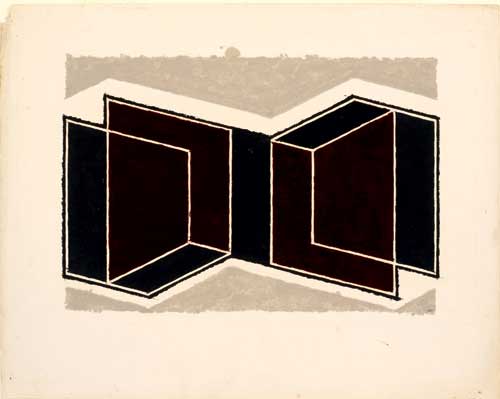

Also at the National Academy and equally wonderful is John Cage: The Sight of Silence, an exhibition of Cage’s watercolors, prints and drawings on paper, accompanied also by Cage’s hand made or natural drawing tools, musical scores, and some wonderful videos of Cage performances. The drawings are mostly loose abstraction, single gestures which at first seem a bit easy and not particularly original, somewhere between traditional Japanese brush painting and spare Abstract Expressionist gestures, but the atmosphere of calm settles over you if you spend some time with the work, the elegance and a quiet that is quite inspiring. The drawings are installed on the wall in an unorthodox manner, based on Cage’s method of chance operations, resulting in a kind of Zen Salon style, with some large drawings way up high, one just above the floor molding, like a little mouse, smaller than the ventilation grate it is next to.

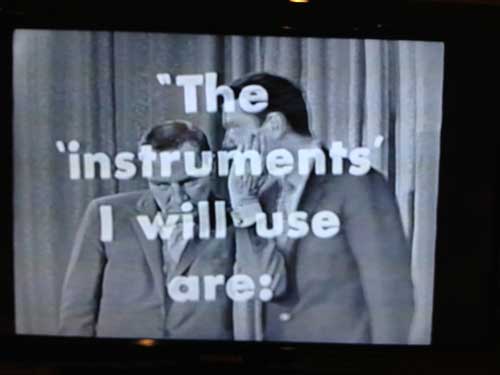

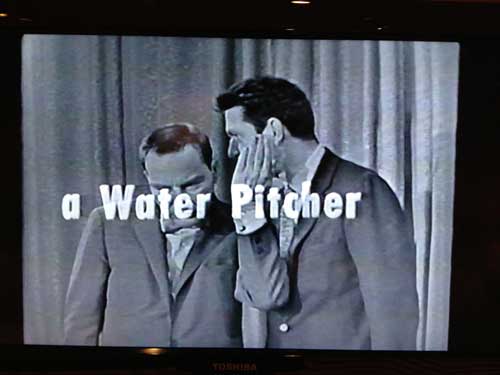

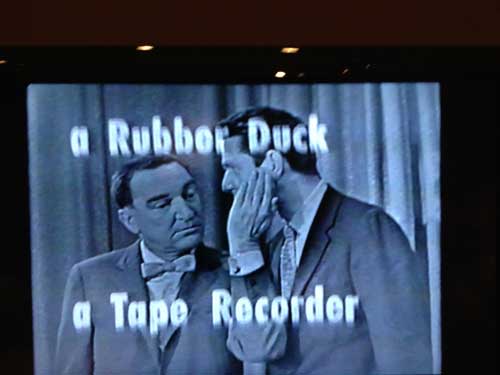

There is a marvelous video of Cage performing Water Walk in 1960, on the ABC game show I’ve Got a Secret, in which the show abandons its usual premise, that panelists have to guess what the guest’s secret is, in favor of presenting a live performance by Cage using all kinds of household appliances and house wares to make sound. It’s great fun, the black and white visuals are beautiful, and if you think about a game show, it is hard to imagine something similar happening with such spontaneity and support.

The show also runs through January 13, don’t miss it!

& I’d like to think that Cage would approve of my pointing out that the building itself is beautiful, a gracious Beaux-Arts mansion, where even the original bathroom fixtures are beautiful:

A block down Fifth Avenue from the National Academy is Picasso Black and White at the Guggenheim.

I like to start viewing exhibitions at the Guggenheim from the top and work my way down, it is less arduous even though it usually means going against chronological order.

When I got out of the elevator at the top, I overheard a woman lecturing to a group of small children, perhaps 6 years old, all scrunched against the ramp with little sketch pads: “every artist has a signature style” she told them, in this case she was referring to Picasso’s distorted profiles of women. This made me think of how, for me, some of the semiotics of Picasso’s work, such as the distorted profiles, are infinitely familiar and not altogether loved oddities, something I grew up with, from my chidlhood they were just there, I knew he was a Protean genius, yet, those profiles, some of the later works…I don’t know. So with that in mind, I have to say that the minute I laid eyes on the works in the show, I realized, this show is going to be Fantastic!!! Not that every work is good, or, rather, not that each work will be to each viewer’s liking, but the vigorous confidence in painting and drawing is palpable and what better vehicle to transmit how painting and drawing are inextricably linked than in black and white and grisaille. Since so many of the works, especially the later works, are dated to a day–for example The Maids of Honor (Las Meninas, after Velasquez) is dated August 17, 1954, and you get the sense that it may have been painted not just in a day, but in an hour or a few hours at most–Picasso doesn’t lose the spontaneity of drawing when he paints. Maids of Honor is huge, the artist looms huge like a giant chimera towering over the room, the whole thing is like a giant crazy sketch, but as I said, fantastic!

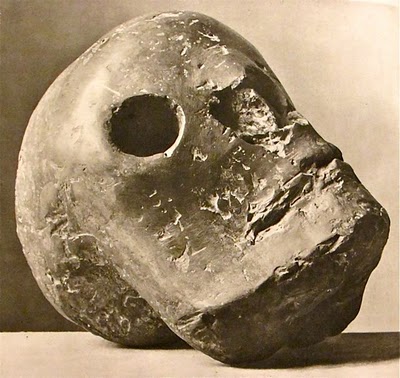

There are at least two powerful images of skulls: a modest size painting from 1947, where a few lines create the inference of the space of a room, so that the skull shifts from a traditionally scaled memento mori painting to a monumental figure within a small painting surface. Nearby is a bronze sculpture of a skull which is one of the powerful works in the show, the image I found online captures it from a different angle than I experienced it in the exhibition and makes it seem a bit less monumental than it is,

The angle of viewing at the Guggenheim makes the eye sockets seem like bottomless craters.

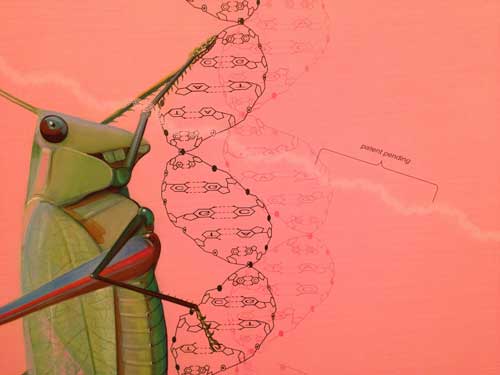

By the time I got to the middle of the ramp, before I even got to a painted sketch for Guernica of the screaming horse’s head, I wrote in my notes, “I would say, at this point, fuck it, this is a necessary show, don’t tell me you’re a painter or interested in painting and not see this show, forget what you know or think you’ve seen, or think you know about Picasso, and just look.” That I would be so emphatic seems silly given Picasso’s totally accepted status as a genius, but it reflects the fact that for many artists Picasso’s relation to subject, to medium, and to drawing, is as foreign as the back side of the moon, and, while no one else could ever be Picasso, the combination of appropriation, expression, and formal invention could still exist as a fruitful area of art production, if one could resist the grip of excessive intentionality.

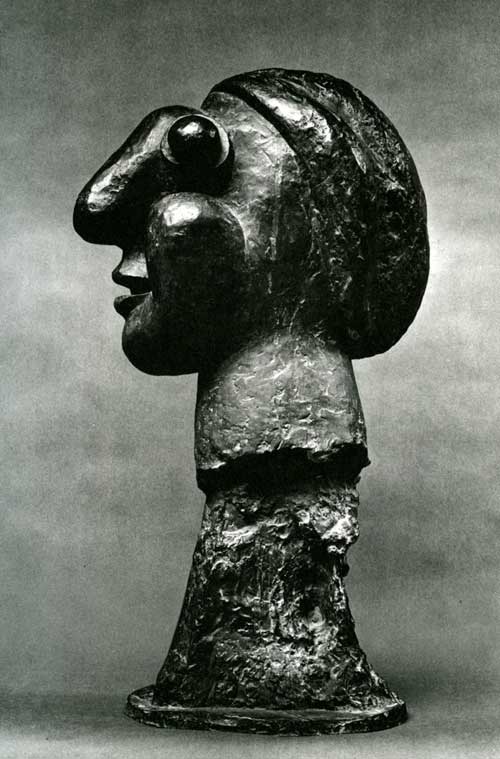

If you start at the bottom of the ramp you can first appreciate Picasso’s traditional academic drawing skills and the delicacy of his drawing line but if you start at the top you get a punch of tremendous force and energy, and many of the works from the early 1930s and late 20s seem somnolent, as if, between The Demoiselles D’Avignon and Guernica, after Cubism certainly, he falls into an academic dream, an Olympian reverie, then BOOM you find yourself a room with large plaster and bronze busts, mostly from 1931. What always seemed to me like a weird given of art, the “signature” profile that the woman was instructing the children to notice, in sculpture makes complete sense.If you start at the bottom you start with the BOOM pass through Olympian reverie and end with the BOOM of the last works, so it’s up to you.

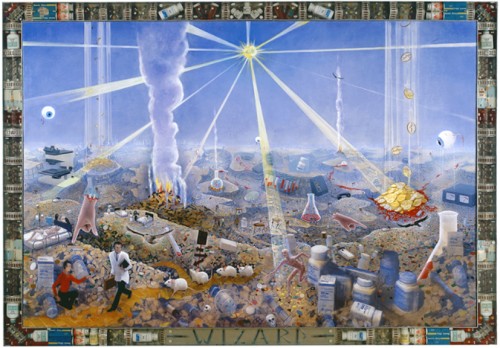

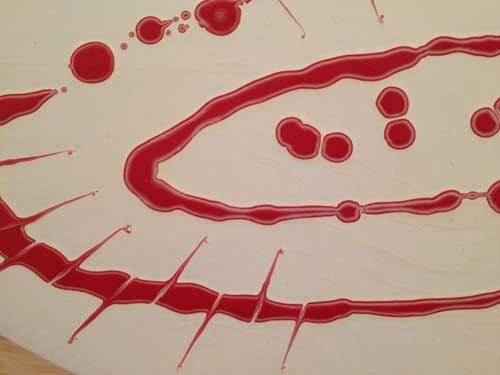

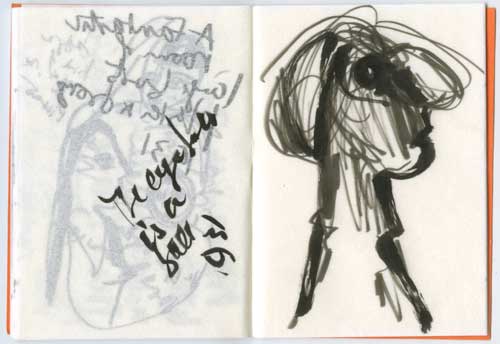

No photography allowed, so I sketched, it seems absurd of course, and presumptuous to present my drawings as any kind of evidence of Picasso’s work, but sketching is also an excellent way of experiencing artwork with your own body. In fact I feel that I have to go back to sketch some of the paintings that I ran out of time and sketchbook room for, but they sparked some ideas for my own work which is a great gift of a great exhibition, that you want to work, that something stays in your mind as a starting point for a work of your own.

Picasso Black and White runs through January 23 but since it’s a block away from the National Academy, it makes sense to make a great day of it and see it before the Shea and Cage shows close there January 13.