I bring to my life as a teacher of art aspects of my own education as an artist. Some elements of that education are part of the history of post war American art and education, for example the shift from formalism in the modernist era to the experiential, experimental, and political tendencies of my graduate education at CalArts in the early 70s. I can sift these experiences through a critical analysis shaped by subsequent developments in art and art education and bring that layered knowledge to my teaching at any moment with a confidence that these experiences are part of a history that can be discussed and shared as part of a legitimated common heritage within the arts.

But there are parts of my experience and of my development as an artist that I realize cannot be extrapolated as easily to anyone else’s use: the most irreducible of such experiences is the fact that my parents were artists and that I watched them work from an early age, as they worked at home.

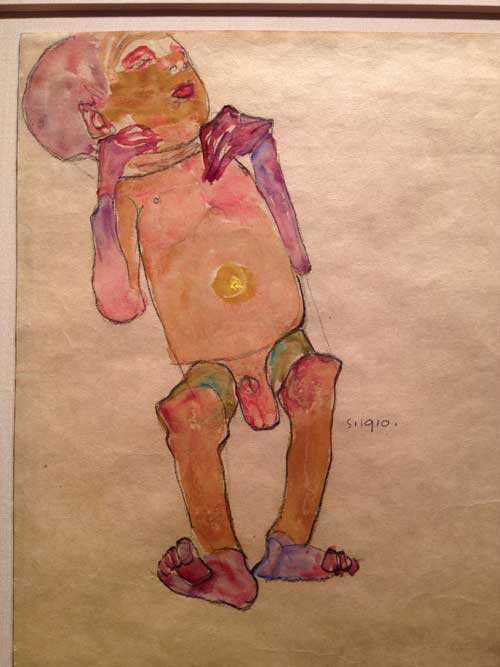

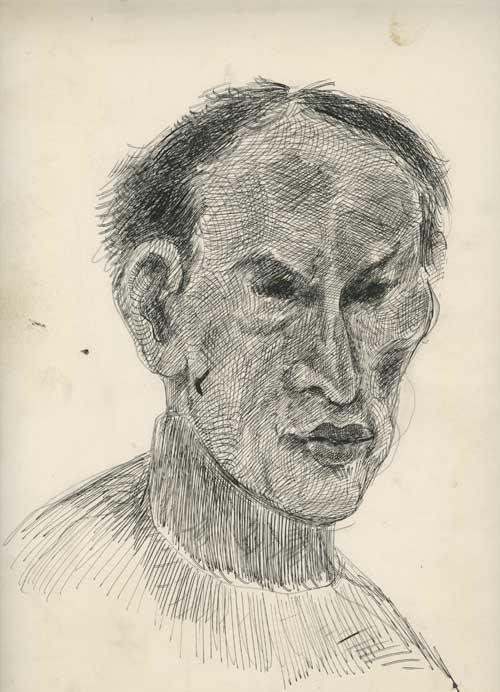

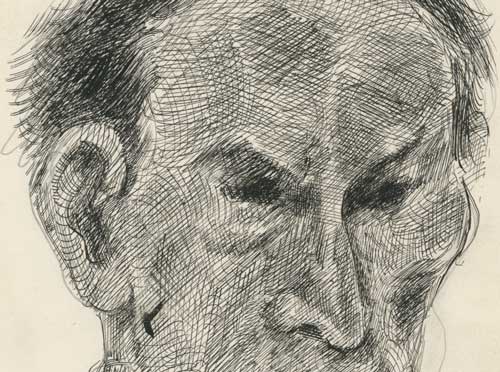

I was reminded of this today when I was putting something back into a closet where I keep most of the works on paper by my father Ilya Schor and noticed some sheets of stiff paper that were just stuck under something else. This closet has a cabinet of Ali Baba character to it: I reach into a dark corner and out comes some wonderful drawing or painting or engraving, on some scrap of paper I hadn’t seen before, and today was no exception to this seemingly magical uncovering of random treasures–at least to me. It is an experience which can be as daunting as it is wondrous, since I am responsible for somehow cataloging, preserving, and determining the fate of the works that I discover. Among the sheets of paper I discovered today was a self-portrait drawing. Judging from the thinness of his face, I would guess it was done in the late 1940s or early 1950s. He worked with India ink and used a small steel-nibbed dip pen, like this one, used by my mother, still in their studio:

Before he went to art school in Warsaw, he had, as a teenager, been trained as an engraver, in Eastern Europe, in around 1920.

What strikes me today looking at this newly discovered self-portrait drawing is the effortless complexity of drawing marks that go into delineating his cheek bones, forehead, eyes, these last never actually outlined, just suggested by an intense deepening flurry of sharp little marks. I am also struck by how the lines of ink seem to go against the grain of form: they do not operate in an academic version of rendering, and yet the convex and concave lines somehow add up to an accurate suggestion of volume and contour.

I share this drawing today because it is just one example of the combination of skill in a traditional art practice–representational drawing–and visual intelligence in action that I could watch up close as a child: the image I always come back to in my memory is of being just tall enough that my eyes were level with my father’s hands as he sat and worked at his table in the workshop off of our kitchen. He was happy to let me watch and to show me a few tricks or flourishes. To watch him summon representation out of such abstraction, out of a flurry of gestures of the hand, with deft skill, speed, focus, and pleasure, was a total pleasure, it was very absorbing, and as good as any magic act a child could watch, and it was a daily practical lesson in art making of a kind that now unfortunately either comes trapped in outdated academic tropes or is simply not part of what a contemporary artist might think was useful or necessary to representing contemporary media culture. Children today are being described as “Generation Swipe,” so the trend away from the steel-nibbed dip pen will continue, as art will continue, but such absorption in an embodied effort to bridge the gap between the real and representation still carries meaning.