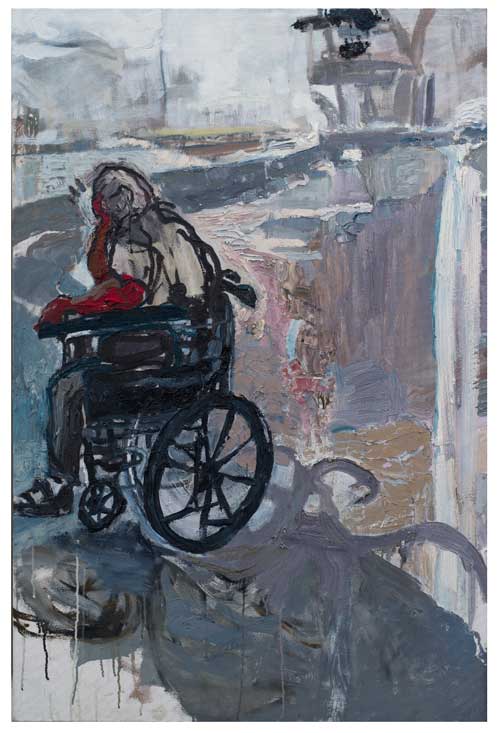

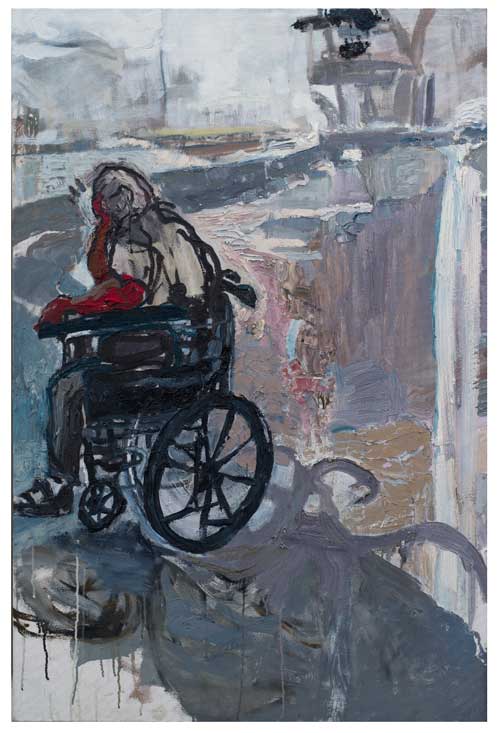

Towards the end of the opening of Susanna Heller’s exhibition at MagnanMetz Gallery of recent paintings, “Phantom Pain,” as the gallery emptied, I happened to witness a profound moment: Heller’s husband, sociologist Bill DiFazio, wheelchair-bound since loosing his left leg three years ago to a terrible illness, rolled his chair up first to gaze deeply and long at a painting by Heller of him sitting in his chair, Lost in Thought. Then he moved purposefully to contemplate the second painting of him in his wheelchair, Phantom Pain. I wondered, what was he thinking when he looked at these portraits, which so exactly mirrored his present self.

Susanna Heller, Lost in Thought, 2013. Oil on canvas, 50″x33″

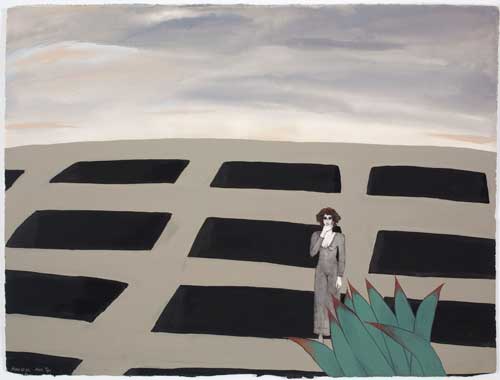

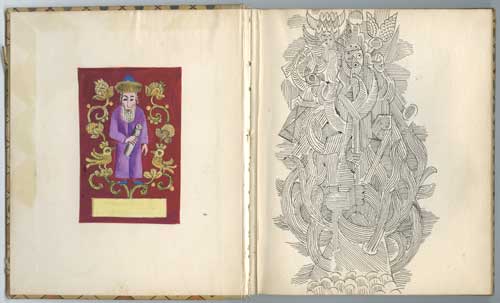

Heller is best known as a painter of New York cityscapes, the site of her epic walks through the city, through the complex linearity and rough materiality of her Brooklyn neighborhood, of subway tracks and bridges, of the patterns of the city streets and island outline seen from the bird’s eye view of her studio in the World Trade Center Tower One in the ‘90s and the patterns of disintegrated metal in the paintings from after 9/11. In the current exhibition this aspect of her work is represented in the first, main room of the gallery by several paintings, including Rolling Thunder (Night for Day), a tour de force nineteen foot wide painting in which she represents the thin, vulnerable, nervous skyline of post-Hurricane Sandy New York City, dwarfed and threatened by the vast and turbulent sky and sea swirling around it.

Susanna Heller, Rolling Thunder (Night for Day), 2013. Oil on canvas. 69″ x 238″

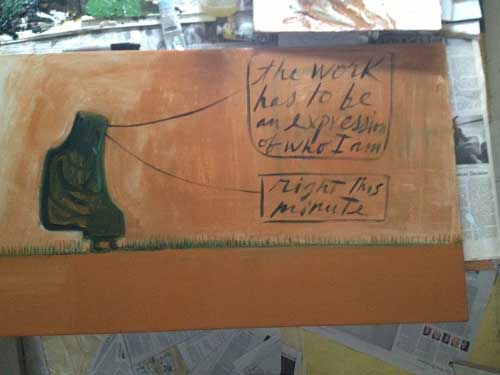

Artist and writer Bradley Rubenstein has an interesting appreciation of this painting in his review of the show, “Spirits in the Material World,” looking at Heller’s views of the city through the “post-apocalyptic” lens of Cormac McCarthy‘s “ruined landscape in The Road,” and Heller speaks of her approach to landscape in a February 2013 video interview on Gorki’s Granddaughter filmed in her studio shortly before the exhibition opened . Her discourse on painting is refreshingly unstrategic and utterly haptic, as she speaks about trying to convey as directly as possible the most intimate and almost primitive aspects of perception, of points of view in relation to up and down, gravity, and scale.

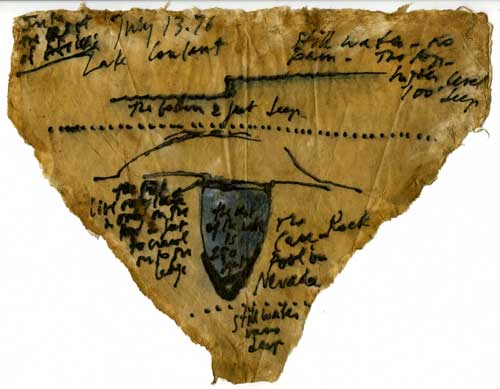

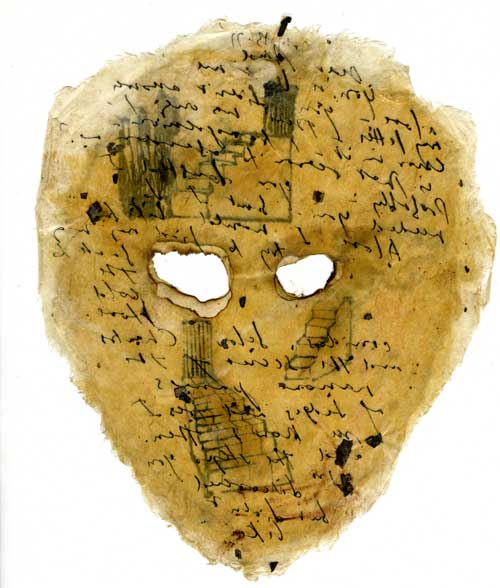

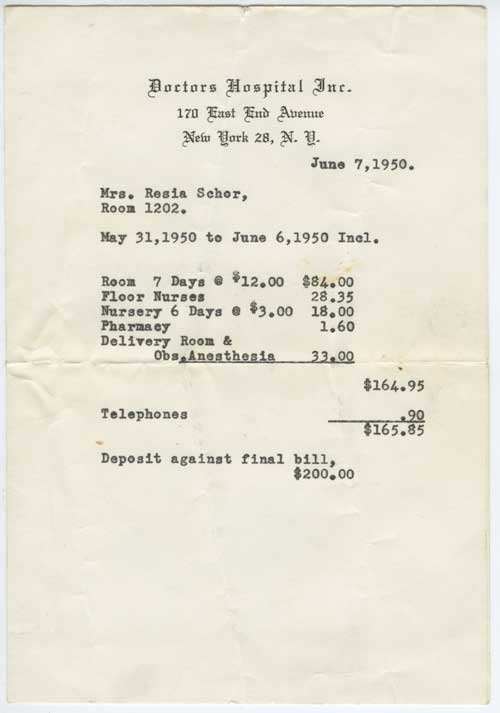

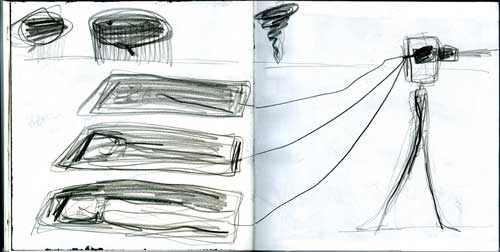

Heller turned her unflinchingly curious gaze to the calamitous injuries her husband suffered when he lost his left leg to necrotizing fasciitis, a horror movie illness that most victims do not survive. The doctors who saved his life, caring for him through over twenty operations in three months, probably never had encountered a patient’s family member so driven to confronting painful realities and so able to turn them into art. She sat in the hospital making hundreds of drawings, of her husband lost in a forest of medical machinery, and of the vistas of the East River soaring outside the hospital window. She drew to save her sanity as she tried to help save his life. Some of these harrowing drawings are installed in a corner of the same room as the paintings of Bill in his wheelchair. Unable to paint during many months of caretaking, in her mind she imagined, catalogued, memorized the paint marks that might articulate what she was seeing. When she was finally able to return to the studio she began to work from these drawings and these mental maps.

In my snapshot, Bill’s back was to Waiting for Dawn. The painting is as raw as his body in those early months, the figure lost, disintegrating, supported by another kind of tower,of all the equipment of the most modern interventional medicine. The painting is vertical, a bed, a kind of falling tower, a coffin with its withered occupant a disintegrating effigy. The paint is rough, encrusted, melting. The man looking at his image in a wheelchair is the man who survived that painting, who left that state of in between life and death to return to an altered life, though the trauma can never be made whole.

Detail, Waiting for Dawn

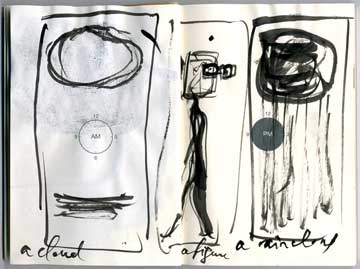

A glorious abstract blob at the top of Waiting for Dawn, maybe the TV monitor for all the medical equipment but maybe also a cloud drifting in from the river is characteristic of the fine line Heller walks between representation and abstraction in her paintings. In her cityscapes, she characteristically fights to achieve a true representation in paint of her experience of urban space: despite her familiarity with the subject, the paintings are worked, sometimes even overworked, paint is scrapped, reworked, erased, painting scraps are glued on.

Heller talked about painting the figure as something for which she had no skills, as foreign as nuclear physics, thus it is interesting that these paintings of immensely difficult painful subject matter are painted with a vigorous simplicity that allows the viewer and the subject to simply be, “lost in thought,” in the turbulent space she is always looking to embody, with all the horror and melancholy of a life transformed by sudden, dramatic, near fatal illness. The human figure and the very particular figure of her husband created a challenge to one of the core aspects of her approach in the studio—that of doubt that haunts every brush stroke, and something new to her work happens in these portraits that is different than the encounter with landscape: in the first portrait of Bill, in the hospital, the overworking or overthinking becomes a powerful expression of the drama of the human body pushed to the limit of survival, where “overworking” is an embodiment of flesh itself in flux. And in the more recent paintings of Bill in his wheelchair every mark seems to have arrived there with a minimum of second guessing and Heller’s line becomes more fluid, her use of outline reminiscent of Alice Neel’s later portraits–each artist is pitiless yet empathetic, though Heller doesn’t veer towards caricature. Abrupt application of painterly paint, impasto outbursts seem open and spontaneous, arriving as thoughts, not as statements or struggles.

In meeting her match in this specific human figure, the haptic approach flows unimpeded.

Susanna Heller, Phantom Pain, 2013. Oil on canvas. 50″ x 33″

These are not easy paintings in their somber subject matter, the phantom pain of mourning and loss but anyone interested in painting, and particularly in seeing a kind of approach to painting that is unsynthetic should go see them.

John Berger writes, in his essay, “Painting and Time,” “Paintings are now prophecies received from the past, prophecies about what the spectator is seeing in front of the canvas at that moment.” He continues, “a visual image, so long as it is not being used as a mask or disguise, is always a comment on an absence. Visual images, based on appearances, always speak of disappearance.” And what was the man seeing when he looked at his portraits that recorded the presence of absence, “phantom pain”? He says he saw in them that his wife loved him and understood him deeply. That is what he says. But the photos suggest something else as well, the ineffable gap between the person and the image: even one’s reflection in the mirror is fundamentally a stranger, a very familiar one perhaps, yet at some level Other.

On the other hand brush marks are indexical traces of the painter in the act of painting, making these paintings, at another level, self-portraits of the artist.

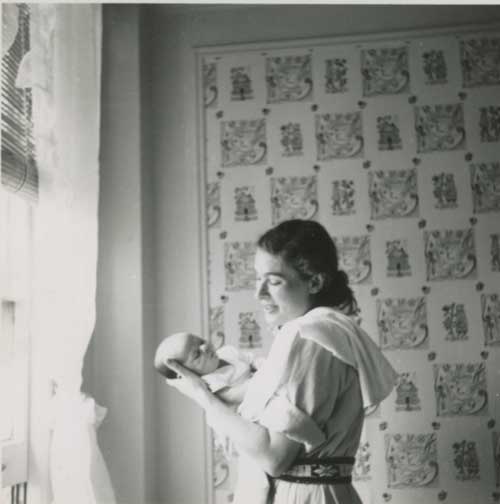

Susanna Heller, studio visit, November 18, 2011, photo: Mira Schor

Phantom Pain runs through April 20

Susanna Heller is represented in Canada by Olga Korper Gallery in Toronto