All I want to do in this post is recommend Mingei: Are You Here?, an exhibition at Pace Gallery in Chelsea which runs through this Saturday April 5. But detours of thought, details of multiple projects, and ulterior motives have complicated the matter: the following is whatever of these threads of thought could be ordered and researched sufficiently and fit into a relatively sensible text against a short deadline.

I’ve been thinking a lot about craft recently. Not from the point of view of a personal practice in crafts such as pottery, weaving, or more contemporary ventures into 3-D printing, not because I want to claim crafts associated with femininity for any kind of identity politics. I’m concerned more generally about an approach to art making that acknowledges the equal importance of making and thinking and I’m committed to the idea that there is a richness of intellectual content inherent in materiality and process.

I find that the direction of my thought is in sync with others in the art world, including the just released April 2014 issue of the Brooklyn Rail which contains a section on craft guest edited by Lowery Stokes Sims whose introductory essay “Beyond The Horizons of Craft: Diversity in the Global Art Market” notes some of the class and gender issues raised by the question of craft or handicraft, as well as the inclusion of ceramic and wood carved sculptures in the Whitney Biennial, as well as the success of recent exhibitions of works in clay and porcelain by artist such as Lynda Benglis and Kathy Butterly.

My train of thought has deep roots in the art works produced by my parents Ilya Schor and Resia Schor, who often worked in areas that had been delimited by high art as being part of the second class of “applied arts,” that is to say craft, such as jewelry and the creation of objects of Judaica. [My introduction to a recent exhibition I curated of some of their work is available on Academia.edu] Although I did not follow their path exactly in terms of the type of artwork I produce, I appreciated from my earliest moments of consciousness the pleasure of working ably with materials and the visual as well as conceptual intelligence of the marks and objects they made and those they collected. My current train of thought about the role of craft, process, and materiality is part of the ongoing negotiation I have engaged in since my earliest moments as an artist, between “wet” (embodiment, materiality, pigmentation, fakture, form) and “dry” (the precession of language, theory, and the concomitant privileging of photographic and digital media), where I have rejected the necessity imposed by the adherents of both sides to chose either one over the other, instead finding a way to step back and forth across the line, or, at best, work within the line of demarcation. My thoughts on craft and process is also the result of stress occasioned by the contrast between the richness of art that exists as living history and as presently available languages and the poverty of visual means and materials that I see some young artists disposing of when the emphasis of their environment is on theory preceding practice and on dematerialized practices rather than ones in any way connected to base materiality or the disciplines of painting and sculpture and their histories.

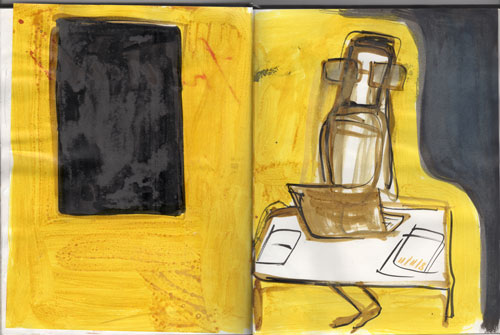

Here is some of what I’ve done in the past few weeks: I spent hours rubbing a decade of oxydation off of a group of twenty small silver and gold objects by my mother; I’ve compared the ornate form of an early twentieth century office chair in the studio of Chaim Gross with the modernist whiteness of office furnishings as represented in the New Museum’s recently announced plan for New Inc; I’ve worked on a series of reversible paintings where I seek to destabilize the hierarchy between the archaic, material, emotive, and the contemporary, digital, cool; I’ve tried to cram readings and rereadings of several books I have on the issue of craft in contemporary culture, including Glenn Adamson’s Thinking Through Craft, Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman, and I’ve trawled Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life for instrumental quotes explaining the way that, at least since the Enlightenment, in Western culture, theory has absorbed the intelligence of crafted objects while arrogating superiority over these practices. I’ve even wasted some time trying to prove that the etymology of the French word métier is the primordial Greek mythological figure of the Titan generation, Metis: although metis means “wisdom,” “skill,” or “craft,” etymology could not take me where I wanted it to go. Instead Sennett posits Pandora as the provocative goddess for his investigation of craft and material culture. I always disliked the myth of Pandora, that a woman’s curiosity would be held accountable for human kind’s ingenuity in crafting destruction.

But for today, all I can do is recommend Mingei: Are You Here? which runs through this Saturday April 5, and view it principally through the lens of the beautiful and heart-wrenching movie it brought to mind, Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1953 film masterpiece Ugetsu.

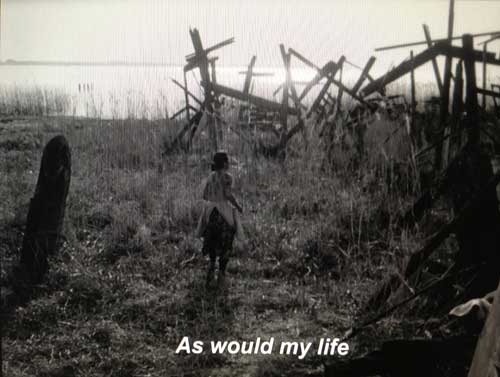

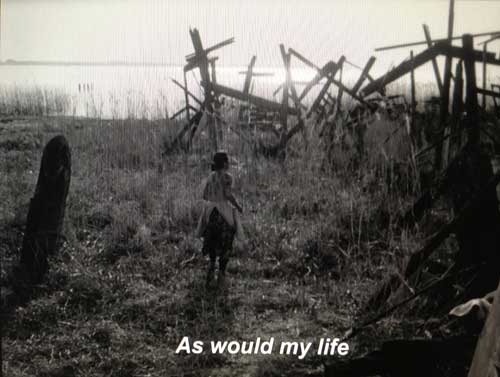

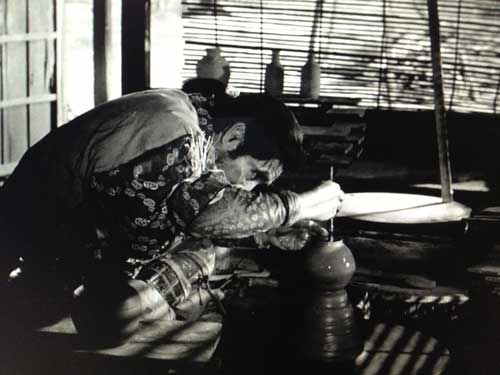

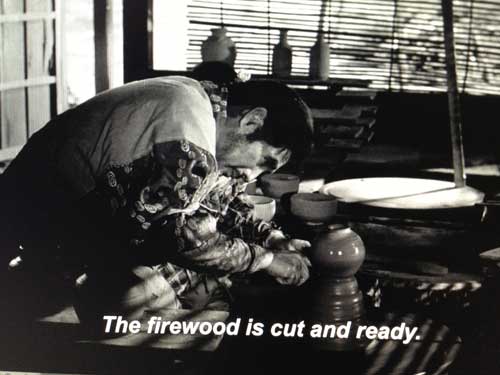

In Ugetsu, the main protagonist is Genjurō, a poor farmer and potter who lives in a humble hut at the outskirts of a small village where he works against time, dreaming of the money he can make by selling his wares at the market. He is not a bad person, but he is crass, materialistic, and selfish: he browbeats his devoted wife and risks their lives to tend to his kiln during the pillaging of their village during a civil war time raid, so that he can complete and take his wares to a larger market town, profiteering during a time of instability. Genjurō, his wife, their young son, and their neighbors attempt to evade bands of marauding soldiers by rowing across a lake to the town rather than walking over land. When, in an eerie foreboding fog, time slows and he and his other companions come upon floating ghostly omens of disaster, he insists on turning back to leave his wife and child alone on the shore, presumably to spare them the dangers that may lie ahead, but effectively abandoning them to cruel fate.

Each scene up to this point in the film is short, the action and the settings are rough. In general the film is very theatrical in its precise and economic use of each scene to advance the narrative as boldly and also as simply as possible, organized like a play where something happens and then the actor leaves the stage and the next diagetic moment can take place, as well as in the way sets, though representing the outdoors, often appear to be shot on an interior stage so that naturalism and artifice are in constant interplay. The efficiency and roughness of plot-furthering scenes only highlights the longer episodes when the film slows and the characters are plunged into beauty, mystery, and terror.

In the bustling market Genjurō is approached by a noblewoman and her elderly maid. These mysterious ladies buy many things and lead him to the noblewoman’s dwelling. There, through the most subtle process of transformation of mise en scene, filmed from above like the survey of a foreign planet, out of what at first seems like an inchoate weed-covered wilderness, an abode of the greatest refinement slowly emerges and he finds himself welcomed into a place of the most exquisite beauty.

His beautiful and aristocratic hostess, Lady Wakasa, dressed in sumptuous heavy brocades and ethereally diaphanous garments plies him with compliments for his craft such as he has never heard and seduces him into a marriage demanded by the spirit of her dead father, a Hamlet like ghost speaking from an empty warrior’s mask. The intense mixture of aesthetic refinement and boundless physical passion are like a dream. He has passed through a portal into a space so marvelous he cannot fully understand what is going on. Throwing himself on a perfectly groomed lawn by the now sparkling lake on a sunny day after a night of sexual passion, he exclaims ecstatically, “‘I’ve never dreamed such pleasure existed. This is exquisite! It’s paradise.”

Incredibly, and without the overt drama of the narrative of Ugetsu, that is somewhat the sensation I had when I walked from Kiki Smith’s exhibition at Pace Gallery in Chelsea, through a narrow passage way into a new smaller wing that Pace has built under the High Line and found myself, without preparation or expectation, in an exquisite, thrilling, soul-soothing, museum quality exhibition of craft objects and artworks, arranged in an inventive, harmonious, and instructive manner for contemplation. In a modest sized rectangular white walled exhibition space, objects of daily use, artifacts ancient and new, paintings and pots, quilts, and kimonos were arrayed on two tiers, hung from the ceiling, against works hung on wall that were subtly dematerialized by natural light coming from unseen skylights along the edges of the dropped ceiling. So-called high art, priceless antique jars, futon covers from the late nineteenth century made from distressed scraps of indigo colored material, all co-existing in an atmosphere of great calm, dignity, and beauty.

The sense of wonderment and confusion came first from the overall sensation of light and the unusual arrangement of objects, and from the immediate sense of displacement: in a gallery in Chelsea, an ancient Japanese garment and a teapot from the 1970s very much like one I own and use.

Filtered light, multiplicity of diverse objects, a kimono here, a teapot there, a painting there. Where was I?

I went back out to look at the wall text: the exhibition is Mingei Are You Here? an exhibition curated by Nick Tremley, originating at Pace London, focusing on works done in the spirit of Mingei, or “people’s art,” folk art, a Japanese philosophical and aesthetic movement conceptualized in the 1920s by Japanese theorist Sōetsu Yanagi. Mingei is a philosophy which “assigned value to and saw beauty in simple, anonymously produced utilitarian objects, signifying a revaluation of popular crafts in the midst of the industrial revolution.” (Nick Trembley, catalogue essay). Mingei was an influential part of an international Arts and Crafts movement that responded to the mechanization of industrial production with a complex respect for low culture, folk produced utilitarian objects of daily usage, and mass produced objects of simple and beautiful design. Yanagi and others rescued from obscurity and destruction humble folk ceramics from earlier centuries from Korea and Japan.

Excursus #1.

*It is of some significance that I had passed from Kiki Smith’s show to this exhibition. The narrow front desk area between the two gallery space had served as much as a portal between worlds as the foggy lake in Ugetsu. Before I happened upon the second, magical gallery space, Smith’s current exhibition had struck me as occupying a great deal of real estate with very little concept or substance, with no sense of a search or a theme, just various objects for purchase, some shiny wares for market, some beautiful (tapestries made from pleasing but not stylistically individuated images created or assembled by Smith), some just merchandise. As I passed through her show, a chronology of mental snapshots of Smith’s shows came to my mind, from the first work I saw of hers in the 1980s at the old Fawbush Gallery on Broadway, which included human figures made of rice paper hanging from hooks, utterly contingent shells of fragile skin that seemed to emerge from the AIDS crisis that Smith was deeply connected to, to a show in about 1993 at Fawbush in his next space in Soho that later became the smaller of Deitch Project’s spaces, the one on Grand Street, where a life-size wax figure of a woman on all fours trailing a chain of entrails seemed to herald a return to a type of essentialist representation of woman that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier, to exhibitions a bit later at Pace Wildenstein in Soho where a kind of nineteenth century fairy tale illustration style of representation and narrative began to slowly erode the criticality and urgency of meaning which had been inherent in Smith’s use of materials and her approach to the human figure in the years she made her reputation, in favor of a more popularly accessible visual language and reference field.

This is only one of several instances of a contemporary artist with a large profile in the market whose early work’s vitality and criticality is long forgotten and often hard to find examples of online: when a young artist is faced with this vacuity within the work of a famous artist without the benefit of a deeper knowledge of the work that created the artist’s reputation in the first place, the disjuncture between name, brand, and artistic depth can only add one more bit of cynicism about the contemporary art market and world.

Excursus #2

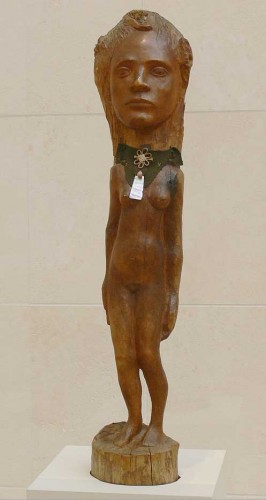

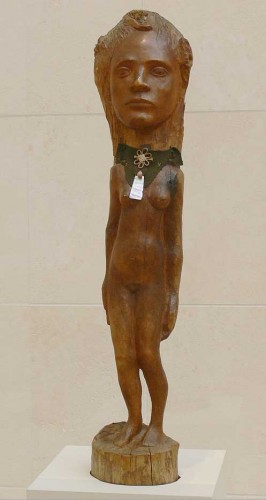

*One work in Smith’s exhibition opens my excursus up to another extraordinary exhibition centered on explorations of materials associated with craft, Gauguin: Metamorphoses at MoMA. In this exhibition two three-dimensional figures of women are outstanding: Oviri (Savage) from 1894, a partly enameled stoneware figure of a young woman whose voluptuous earthy beauty is emphasized by the earthen burnt siena colored surface of her skin yet undermined by the resemblance of her pose to that of a deposition of Christ–Gauguin thought so highly of this work that he wanted it placed as his gravestone–and Tahiti Girl (c. 1896), a figurative sculpture that Gauguin crafted in wood, adorned with felt, silk, seashell and mother of pearl jewelry and amulets. Tahiti Girl‘s head is huge in relation to the rest of her body, nearly life size in relation to the half-sized body, with her legs tapering down like those of an elfin creature in a child’s fairy story. The work is exhibited three-dimensionally so that the process of crafting is made fully visible: what appears from the front view to be a continuous figure, with the head and body part of the same piece of wood, in the back is revealed to be a separate piece of wood, bolted to the body, a huge ghost-like bulbous shape left in an unfinished state, hewn with rough chisel marks, unlike the uncannily smooth burnished surface of the front. The necklace veils the juncture. She is as much as a spirit figure of exotic female beauty as the Lady Wakasa. And in Gauguin’s Noa Noa: The Tahitian Journal, Gauguin writes of sensual intoxication similar to the rapture expressed by Genjurō: “Plein silence. Mais quelles harmonies violents dans les parfums naturels qui grisent l’artiste voyajeur? Que de beaux fruits dans l’eclat polychrome des feuilles, des fruits, des fleurs!” Total silence. But what violents harmonies in the natural perfumes which intoxicate the artist voyager? What beautiful fruits in the brilliant multicolored leaves, fruits, flowers!”

In sum, aesthetic responses are always set in a context: here the emptiness of much that appears as central in the art market is contrasted with the inspiration that can come from transformative works by an artist that you don’t even particularly love. The Smith show, empty of concept, composed of a few shiny wares for market, Gauguin’s transported responses to inchoate and incomprehensible beauty of another civilization both set the stage for my response to the calm beauty of the objects in Mingei are you here?

*

It is revealed to Genjurō that the Lady Wakasa is a ghost whose soul has wandered in search of the the full experience of a woman’s sexual life and true love, which her murder during the Civil War had preempted. Recalling his wife and child, he manages to flee her desperate embrace, waving her father’s sword at her, he throws himself into the dark night. When he awakens he finds that her exquisite home is a burned-out ruin, the impeccable lawn by the lake a tangled field of brambles and weeds.

I returned to see the exhibition Mingei Are You Here? two weeks later and had a more complex and nuanced experience. While I did not suffer so dramatic a transformation of my aesthetic experience as Genjurō, discovering that his beautiful love is a cursed phantom trying to take him to the spirit world forever, nevertheless I began to distinguish differences in what was arrayed so artfully that at first I had been so overwhelmed with wonderment, while my pleasure in the exhibition catalogue’s intriguingly Mingei-style design, with its modest brown paper cover and shoji-screen like fold out inserts, was slightly undermined by some of the historical complexities of the Mingei movement, including its uses to xenophobic assertions of Japanese nationalism in the pre-World War II period.

Unknown maker, Ainu Attush robe, late 19th c.

I realized that I experienced a hierarchy of fascination, with the most ancient artifacts and the most modest and simple of the contemporary mass produced objects at the top. Among my favorite works are a wooden kettle hook hanger from the Edo-Meiji period (nineteenth century) whose utility is not clear to a contemporary Western viewer, so that the experience is principally aesthetic or material: the dark reddish-brown patina of the wood and the curvature of the shape, a curved form that is also a box; a conical shaped object of bamboo and bronze that is a Falcon basket from the Edo period; a beech plywood and brass Butterfly stool manufactured by Tendo Mokko from 1954; and a brushed stainless steel kettle designed by Sori Yanagi in 1994 and still in current manufacture–I have one just like it. Of the modern art works, small granite sculptures by Isamu Noguchi seemed particularly powerful when placed next to these anonymous folk objects: in one work in particular, Untitled (Small Torso), the stone is allowed to be itself and the effort necessary to inscribe any mark into it, even one or two incisions, is a powerful trace within the work.

Each of these objects has an absolute tangibility as well as an ineffable quality that cannot be captured or fixed, although daily usage and absent-minded but constant concentration and contemplation can bring it close. Thus the beauty of the humble mass produced kettle from the 1970s:

On the wall, 2 oil paintings on canvas by Lee Ufan: Dialogue, 2007 and With Winds, 1989; Butterfly Stool by Sori Yanagi, 1954; Sgrafo Modern porcelain, designed by Peter Müller, c. 1960-80.

In the context of the old and often the anonymous, some contemporary works looked much better to me than they might have in other contexts: thus, a painting by Lee Ufan suddenly made a different kind of sense as the backdrop for a series of small curiously shaped white porcelain shapes of the Sgrafo Modern-Korallen Series (design by Peter Müller, c. 1960-1980) and for some ancient Japanese folk rain gear and a backpack made of indigo dyed cotton and layers of fiber than it does as just one more work in the current surfeit of contemporary “casualist” or “provisional” abstraction.

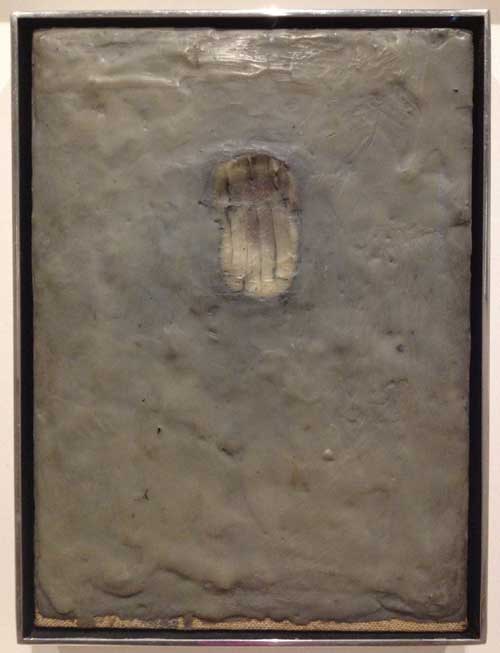

There were also a number of large contemporary hangings, sculpture, and paintings that I realized that I was simply blotting out: works such as Mai-Thu Perret’s enameled ceramic gold glazed slab, When I look I do not see, when I listen there is no sound (2011), Trisha Donnelly’s large Untitled slab of Stone Azul Macaubas, a mauve stone whose high polish reminded me all too much of what one might find in a deluxe bathroom of a new four-star hotel in Dubai, and even Steven Prina’s brightly painted Blinds. Their optic effect felt jarringly vulgar in the context of Mingei’s embrace of the modest, which parallels the aesthetic principles expressed by Jun’ichiro Tanizaki in his 1933 artistic and ethnological manifesto, In Praise of Shadows. They were gaudy ghosts of the market but, luckily, irrelevant to the impact of the exhibition as a whole.

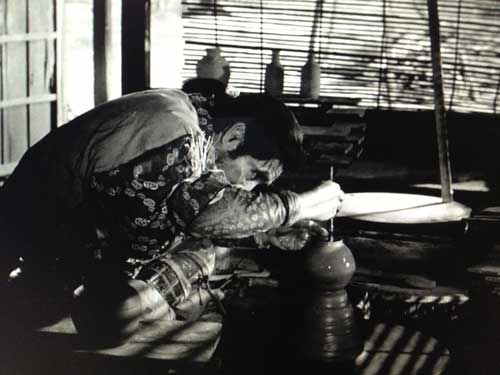

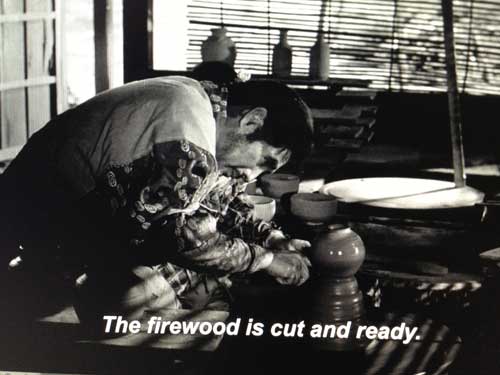

At the end of Ugetsu, Genjaro is again working at his potter’s wheel. He has been transformed by everything that he has experienced, by the spectral encounter with aesthetic perfection in the person of the Lady Wakasa , and by the spectral reminder of the warm intimacy of family life which he had taken for granted when he had it, of which one precious reminder is given to him in a final ghostly encounter. In contrast to the rushed sloppy way he churned out as many pots as he could for the market when we first saw him, now he lovingly crafts a single pot, light catching the gleam of the wet clay as it turns and as the ghostly voice of his wife expresses her joy and admiration for his work, which at last fulfills her hopes for him. The film ends. We see him fire his kiln but we never see the completed work. Yet the intimation is that it will be beautiful, that all the suffering will be expressed in the beauty of a common object, crafted with love.

Strangely the texts I have read on Ugetsu don’t focus on the film as an allegory of art making. But I see it that way. I also can see that the moral of the story, that great art is not arrived at through crass commercialism and personal ambition for riches, but through the infusion of suffering and loss into a work done within a process of craft (and I use that term in the most expanded manner possible including so-called deskilled processes) is for some an outdated idea of who the artist is and what art is in contemporary culture. The quaint notions of objecthood, craft, sacrifice for art, aura–for what could be more auratic than a single pot which has been wrought–with humility and selflessness–over the souls of two dead women?–surely these are not characteristics directly applicable to contemporary practice.

Unknown maker, Sake Bottle, 17th century

So how does one get from the empty studio in which a young artist may be sitting on his tuffett like Little Miss Muffett, trying to bridge the gap between theory/ intentionality/ideation and artwork which may have some materiality or emotive weight? How does one get from the merely illustrative to the internally performative?

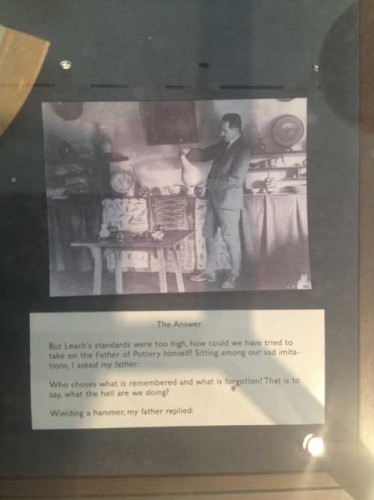

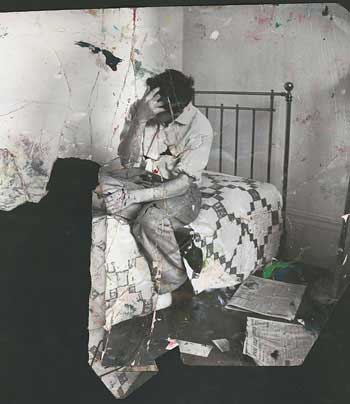

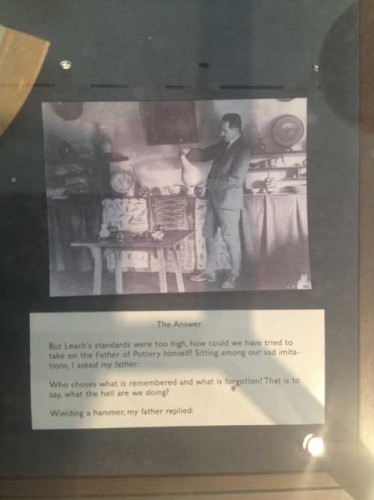

One answer is offered by one of the contemporary works in Mingei: Are You Here?, Simon Fujiwara’s Like Father, Like Son (2013): within glass vitrines there are two plates, one whole, one shattered, and four photos with typed text on cards such as one might find in a small local ethnographic museum of a slightly earlier era. The text relates what appears to be a personal narrative by the artist, about his absent Japanese father, pottery lessons, and the work of Bernard Leach, a British man who was a recognized master of Japanese traditional pottery in the early twentieth century. Yet, despite the first person voice, the stylistic signifiers and subtly shifting pronouns signal that this is an unreliable narrative even if some or even all of it is based on autobiography. In contrast to many of the other works of craft and art in the exhibition, this is clearly a contemporary conceptual artwork, with all the irony and distantiation than comes with that designation, rather than a straightforward work of craft. Nevertheless something about how one might proceed in this moment of imbedded disbelief in the kind of authenticity of the more historical works in the exhibition is implicit in the conclusion of the piece:

To make something you have to break something, to have something to break you have to make something–it does not have to be a plate, or a painting, but it has to be something you can see clearly enough to wield the hammer.

*

Further reading on Mingei: Are You Here?

“Mingei: Tradition and Craft; Simplicity and the Everyday” by Altoon Sultan

“‘Mokujiki Fever’ Endures” by Alice Rawsthorn

“Mingei: Are You Here?” by Michael Straus

Further reading on Ugetsu:

“Ugetsu: From the Other Shore” by Phillip Lopate

“Ugetsu” By Keiko McDonald

Ugetsu monogatari, 1953, complete film, my description of the film and the stills in no way convey the profound impact of the cinematic whole which by the end of the film will have efficiently reached into your heart and ripped it out [this link may not last]