If you are an artist or just about anyone participating in the art world, this is not the week to email anyone, or send announcements about anything, or, indeed write a blog post that focuses on anything but the shiny smooth surfaces presented on art media coverage of the fairs: nothing will be heard except the concentration of commerce in Miami.

The cats are away, so at what will the mice play?

Meanwhile at night the streets and highways of New York resonate with people materializing in one neighborhood and then another, chanting “I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe.” What can the mice who are not gathered in the brightly lit agora, and those who are, do about the present injustices, if anything? What is the worth of a single artist’s voice or even the voice of a people?

This summer I was captivated by an essay by Austrian philosopher Gerald Raunig, “Josephine, Or Streaking The Territory,” in his 2013 book Factories of Knowledge, Industries of Creativity.Through it I learned of a short story by Franz Kafka, his last short story, “Josephine, the Singer, or the Mouse Folk.” The concept of an artist’s work as a “weak event,” barely different from the work of the other mice people yet vital to their sense of community, the image of the artist who is as conceited and contemptuous of her audience as she is justifiably admired and heroic, the artist whose song is at best a “gentle streaking of the territory”–all these weak indicators of the generous egotism and valiant futility of the artist offer a model for artistic engagement with the body politic which, by recognizing futility and significance alike, might give an artist some tiny bit of hope for the meaning of the work.

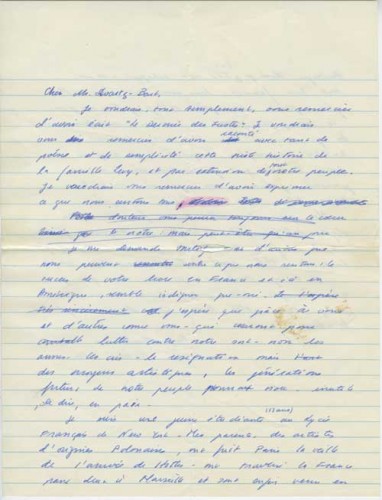

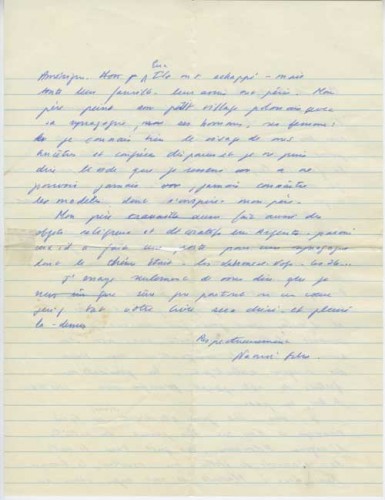

Here are the pages of the short text interspersed with some quotes from Kafka’s story:

Is the artist any different than the rest of her people?

Among intimates we admit freely to one another that Josephine’s singing, as singing, is nothing out of the ordinary.

Is it in fact singing at all? Although we are unmusical we have a tradition of singing; in the old days our people did sing; this is mentioned in legends and some songs have actually survived, which, it is true, no one can now sing. Thus we have an inkling of what singing is, and Josephine’s art does not really correspond to it. So is it singing at all? Is it not perhaps just a piping? And piping is something we all know about, it is the real artistic accomplishment of our people, or rather no mere accomplishment but a characteristic expression of our life. We all pipe, but of course no one dreams of making out that our piping is an art, we pipe without thinking of it, indeed without noticing it, and there are even many among us who are quite unaware that piping is one of our characteristics. So if it were true that Josephine does not sing but only pipes and perhaps, as it seems to me at least, hardly rises above the level of our usual piping—yet, perhaps her strength is not even quite equal to our usual piping, whereas an ordinary farmhand can keep it up effortlessly all day long, besides doing his work—if that were all true, then indeed Josephine’s alleged vocal skill might be disproved, but that would merely clear the ground for the real riddle which needs solving, the enormous influence she has….

After all, it is only a kind of piping that she produces. If you post yourself quite far away from her and listen, or, still better, put your judgment to the test, whenever she happens to be singing along with others, by trying to identify her voice, you will undoubtedly distinguish nothing but a quite ordinary piping tone, which at most differs a little from the others through being delicate or weak. Yet if you sit down before her, it is not merely a piping; to comprehend her art it is necessary not only to hear but to see her. Even if hers were only our usual workaday piping, there is first of all this peculiarity to consider, that here is someone making a ceremonial performance out of doing the usual thing.

But we listen to the artist precisely because of her imperfections, which attract more than the artist who is trained and proficient:

She gets effects which a trained singer would try in vain to achieve among us and which are only produced precisely because her means are so inadequate. …This piping, which rises up where everyone else is pledged to silence, comes almost like a message from the whole people to each individual; Josephine’s thin piping amidst grave decisions is almost like our people’s precarious existence amidst the tumult of a hostile world. Josephine exerts herself, a mere nothing in voice, a mere nothing in execution, she asserts herself and gets across to us; it does us good to think of that. A really trained singer, if ever such a one should be found among us, we could certainly not endure at such a time and we should unanimously turn away from the senselessness of any such performance.

The artist is the individual who steps forward at times of need and gives all her strength to the song:

Our life is very uneasy, every day brings surprises, apprehensions, hopes, and terrors, so that it would be impossible for a single individual to bear it all did he not always have by day and night the support of his fellows; but even so it often becomes very difficult; frequently as many as a thousand shoulders are trembling under a burden that was really meant only for one pair. Then Josephine holds that her time has come. So there she stands, the delicate creature, shaken by vibrations especially below the breastbone, so that one feels anxious for her, it is as if she has concentrated all her strength on her song, as if from everything in her that does not directly subserve her singing all strength has been withdrawn, almost all power of life, as if she were laid bare, abandoned, committed merely to the care of good angels, as if while she is so wholly withdrawn and living only in her song a cold breath blowing upon her might kill her.

The audience is in part competitive and dismissive, in part enraptured:

But just when she makes such an appearance, we who are supposed to be her opponents are in the habit of saying: “She can’t even pipe; she has to put such a terrible strain on herself to force out not a song—we can’t call it song—but some approximation to our usual customary piping.” So it seems to us, but this impression although, as I said, inevitable is yet fleeting and transient. We too are soon sunk in the feeling of the mass, which, warmly pressed body to body, listens with indrawn breath.

The artist feels “it is she who protects the people. When we are in a bad way politically or economically, her singing is supposed to save us, nothing less than that, and if it does not drive away the evil, at least gives us the strength to bear it.”

Those who feel that art must have an objective function based on objective research that is objective, or those who both insist that art fulfill a transformative critical function yet reject fantasies of resistance, might find what Josephine gives the people a bit too idealistic:

Here in the brief intervals between their struggles our people dream, it is as if the limbs of each were loosened, as if the harried individual once in a while could relax and stretch himself at ease in the great, warm bed of the community. And into these dreams Josephine’s piping drops note by note; she calls it pearl-like, we call it staccato; but at any rate here it is in its right place, as nowhere else, finding the moment—wait for it—as music scarcely ever does. Something of our poor brief childhood is in it, something of lost happiness that can never be found again, but also something of active daily life, of its small gaieties, unaccountable and yet springing up and not to be obliterated. And indeed this is all expressed not in full round tones but softly, in whispers, confidentially, sometimes a little hoarsely. Of course it is a kind of piping. Why not? Piping is our people’s daily speech, only many a one pipes his whole life long and does not know it, where here piping is set free from the fetters of daily life and it sets us free too for a little while. We certainly should not want to do without these performances.

What will the artist have contributed? What will be left of the song?

The time will soon come when her last notes sound and die into silence. She is a small episode in the eternal history of our people, and the people will get over the loss of her. Not that it will be easy for us; how can our gatherings take place in utter silence? Still, were they not silent even when Josephine was present? Was her actual piping notably louder and more alive than the memory of it will be? Was it even in her lifetime more than a simple memory? Was it not rather because Josephine’s singing was already past losing in this way that our people in their wisdom prized it so highly?

Georg Flegel (1561-1638), Still Life with Mouse and Parrot, Coll. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.