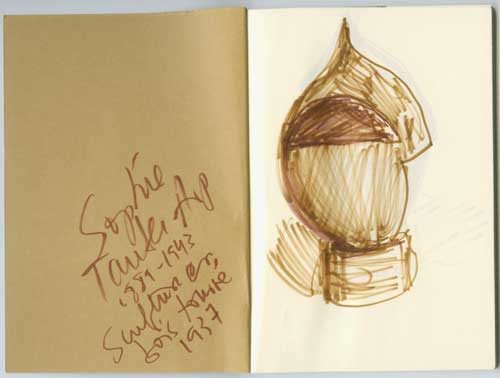

I just saw a repost of “The Problem of the Overlooked Female Artist: An Argument for Enlivening a Stale Model of Discussion,” an article by Ashton Cooper published on Hyperallergic over a year ago in January 2015 and am discussing it here because it is a subject that is all too close to my own experience and also to what some of my recent work was “about”–my drawings in which a half cadaverous but still living bleeding woman artist is confronted by the two polarities or scenarios of what one might call terminal inclusion, “still too young” and “not dead enough.” I also wrote about this whole finally giving very old women artists a bit of greater visibility and recognition–100 is the new 70–phenomenon recently in fashion in the art world, on A Year of Positive Thinking in posts such as “Just a short message from Venus” from June 24, 2015 and https://ayearofpositivethinking.com/2015/06/01/miss-piggy-and-madame-de-beauvoir-a-new-fable-of-la-fontaine-cochon-et-castor/ from June 1 2015.

In her text Cooper examines the phenomenon and particularly examines the language used to promote it, a method that is useful in the effort to denormalize an inequity that has become second nature,

As a onetime writer and editor for a company that owns two art magazines and an art-centric website, I can attest that art journalism is in no way immune from conventions that ostensibly champion women artists, but in fact perpetuate problematic narratives about them — tropes so prevalent, even I have operated within them. In particular, I’m thinking of the widespread myth of the “overlooked,” “forgotten,” and/or “rediscovered” female artist.

I also found very significant one of Cooper’s conclusions which is the importance of looking at the actual socio-economic and aesthetic conditions of the women artists’ lives and careers in those years they mysteriously were not “discovered” enough…in fact when they were doing really interesting work, were part of interesting communities, while young men of their circle were getting mid career retrospectives at major museums before they reached the age of 40.” Cooper continues,

So instead of focusing on the moment when these women were finally “found” — and by extension, on the institution that was gracious enough to do so — I propose we talk more about that period where she was toiling away in obscurity. What was she doing then? Where was she showing? Who was she in community with? How did her practice change? What forces of exclusion did she face? Instead of the tired story where a masculinist force deigns to discover, find, or recognize female artists, what if we tried to also understand the material realities of these women’s lives? Ultimately, we would not be so dependent on the recognition of the art world’s skewed mainstream if we used these histories as case studies to define different kinds of success.

Parenthetically, I have also in the past noted that the time period when artists produce the work that later has the greatest monetary value is the period when they are working in relative obscurity but in a lively artistic community. There is something to be said for privacy and even for the productive nature of being forced to clarify and intensify your work in the effort of making yourself seen, heard, understood. Success right out of graduate school, for example, means the ideology of the work is never tested against lack of response or changing fashions. This is a paradox, of how the market alters artistic production–without some recognition and market success an artist’s struggle to produce work can be too great, if you add to this general reality the inequities created by gender, which are well established and studied, you have a much greater difficulty factor enhanced by the fact that women who are in between, neither young and sexy or very old with their transgressiveness now innocuously “cute” are of no interest to the journalistic narrative Cooper discusses, and yet achieving market success young can put stresses on work that turn interesting challenges and private intensities to public–“merchandise” as I quoted my mother recently. Too early recognition can be a trap, but too late can be a tragedy of sorts, when the artist is no longer able to use the success and the financial security to grow new work and realize long held dreams for their work because they are simply too old and tired or ill..or dead. Louise Bourgeois is the one of the few if not the only example of a woman artist who began to get some real material and critical success in her 70s but then was able to have two more decades to use that success to finance ambitious new projects–that is so so rare.

In terms of language, I would think in terms of replacing “rediscovered” with “hidden in plain sight,” to mark the fact that many of the women artists who eventually may be lucky enough to be “rediscovered,” as Cooper points out, have in fact been visible all along, if you bothered to look, close to the center, exhibiting, lecturing, writing, respected even, but always with the sense of auditioning for a part they already have. And whenever an older woman artist is “rediscovered,” there a lot of, mostly women, artists and art historians, shrugging their shoulders because they have been teaching and writing about and been inspired by that artist’s work for years. The in plain sight part is obvious, the hidden is in the blindness that gender bias and ageism bring to the situation.

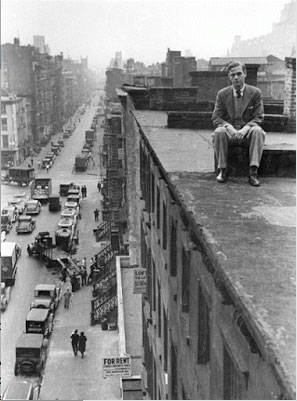

As I have tried to explain recently to someone, it is Not Normal that an artist like June Leaf has to wait until she is in her mid 80s to get a show at the Whitney, not a true retrospective mind you, but a drawing show with some sculpture in it, in the small gallery off the lobby. It’s not cute or great, though of course it is wonderful and much deserved and well past due, but there is nothing normal about it in the wider view of young male artists having museum retrospectives at barely the 10 year mark in their careers.

While we should celebrate these late moments of more public recognition for some older women artists and be grateful to have the opportunity to see some of their work, we should not normalize the inequity and abnormality of the phenomenon that Cooper discusses.