Hello.

A Year of Positive Thinking has been on hiatus since late February while I moved out of the loft where I lived and worked for 33 years into the apartment where I grew up.

All moves are overwhelming endeavors and often fraught. The circumstances of this move had particularly infuriating aspects contributing to a less than positive outlook. I’ll just make a few general statements, and for legal reasons I’ll say, quoting Mr. Jaggers in Great Expectations, “I’ll put a case to you. Mind! I admit nothing.”

First, “Ownership occupancy eviction” is an apparently idiot-proof loophole in the New York City Rent Stabilization Law (the burden is on the tenant to prove the landlord is lying about his stated plans, and this is nearly impossible, though lying is a near certainty, and even if the landlord is claiming a seventh floor walk up for a 90 year old mother, or that his poor sick daughter must live in the smallest darkest most poorly appointed space in the building he has just given her a 5% ownership in so that she can be used as a spurious proxy to evict a 60 year old artist before she turns 62 and would be legally out of reach for such maneuvers, the tenant would have to pay tens of thousands of dollars to prove the absurdity of the proposition–how you say in English, This is a stick-up).

Second, young, mostly British in the particular case of my building, people, or the financial corporations they work for or own, are able and willing to pay $22,500 a month for approx.3750 usable square feet on a street with a healthy street population of rats, that’s right, $270,000 a year rent in a city where the median income even just for the Borough of Manhattan is about $65,000 a year.

Third, it’s possible to turn a small 7 story loft building with only 8 tenants in it into a gated community: to the young blond “neighbor” holding her young daughter in her arms who waited until I got out of the elevator this winter before keying open her floor so I wouldn’t see which floor she lived on, I say, bravo, you learned your survival-in-New-York-City lessons well, you can never be too careful, who knows what a middle-aged woman carrying her groceries could do to you if she knew not just generally but exactly where you live.

Also, striking the set of a lifetime of artworks, papers, and belongings is a brutal task, backbreaking and filthy; further, things taken out of a drawer no longer fit back into exactly the same drawer when you try to put them back exactly as they were before. Clothes multiply like tribbles. And once things are ripped from their natural place, where they had slowly accreted into the archeology of your life, it can take a whole day just to find the right place to put one plate. And you can’t write when your books, papers, artworks, art supplies, clothes, and the rest of your wordly belongings are in over 150 boxes through which you must navigate a narrow path to your computer, because you can’t think until some modicum of order and personal geography is restored.

Between last September and November I worked two or three days a week with a wonderful assistant packing hundreds of artworks made by my parents as well as their collection of books, and the many objects they collected. What in essence was about 100 years worth of life and art was to be put into temporary storage so my family’s apartment could be modestly repaired and refreshed. In that process I basically touched every single object, book, piece of paper, photo that accounted for their lives, mine and my sister’s, but each only for a tantalizingly brief instrumental moment since, even though many such moments of contact sparked the idea for a brief aesthetic and politically autobiographical essay, the packing had to move forward against an inexorable deadline.

In February these possessions were returned to the apartment, the furniture set in place but the artworks and objects staying in boxes. Then I had to dismantle my loft, which, half a lifetime ago, on a $4700 budget in 1978, I had designed in the barest, simplest way possible to serve my needs as an artist. Though small and with no natural light, it was a space with an interesting ambiguity of proportion–a friend’s precocious child, now an architect, once visited and declared, “C’est grand, mais c’est petit” (It’s big but it’s small)–and a tremendous unity. No matter whether I was cooking, painting, writing, watching television, I was living inside my brain, with all my books , paintings, texts, and collection of china visible to me at the same time.

So I have bucked an American axiom, that you can’t go home again. I have returned to the building I was born into, and to the beautiful apartment I moved into when I was five–the day I first saw the apartment with my parents, taking the elevator from our smaller apartment a few floors below, is the moment where my conscious memory truly begins. Thus infuriating circumstances have precipitated my taking on part of what I consider my destiny, that is to archive and to mark as best I can the memory of my family’s life, particularly my parents’ lives in Warsaw and Paris before the War, their escape from Nazi-occupied Europe, and their creative life in New York as the background for the path I have taken in my life as what I would call an inflected American.

There has been too much to do to have time to feel haunted in my new old home, though the first time I took a bath in the deep ceramic tub there was at least one moment when I felt the quiver of time’s arrow in a 2001: A Space Odyssey see yourself as the old man in the next room and the fetus floating towards Earth kind of way: I was myself in the moment in mid-life enjoying a small luxury, and I was also myself as a small child in the same bathroom with my two parents checking in on me to see if I was alright, and I was myself five years ago peeking through the bathroom door to make sure my 95 year old mother was safe in her bath, and possibly I was also myself at 95 taking a bath in the very same place. As if in an eerie commentary on that shift through time, when I got out, the bubbles had taken the following form.

Now I get to gaze again daily at the objects whose beauty and character as the natural atmosphere of my childhood shaped my aesthetics. My parents didn’t have a chair that didn’t creak with age or threaten to collapse altogether, but the sometimes centuries old wood shone darkly and those gleaming dark ochres and rich browns are primary hues in my painting. If they could adorn their rented room in Marseilles with flowers while hoping their visa to America would arrive before the Germans, the minute they could put two cents together in New York they hunted through antique stores, pawn shops, and Parke-Bernet auctions for furniture and antiquities, though the only antique pottery they could afford to buy was often shattered like a eggshell and glued or stapled together so that it seems that a breath or a touch could shatter them, but their glazed surfaces lurk under the manner in which I use oil paint, using stand oil for its ceramic like shine or glaze.

Each object seems to repeat the same metaphor of my family’s life and work: treasures with frustratingly little material value because of their condition yet with the immeasurable value of beauty, history, age and time, fragility itself. There are many times when the weight of so many histories, many of whose details I don’t know, and the fragility of the objects containing them makes me nearly scream with fear, but what a richness, I know.

Here are a few of the things I have touched in the past months:

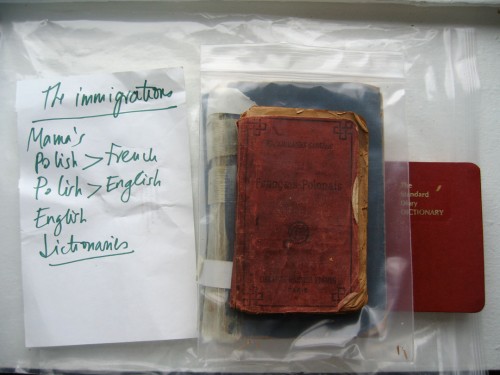

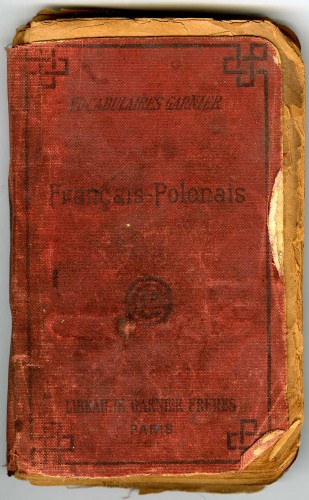

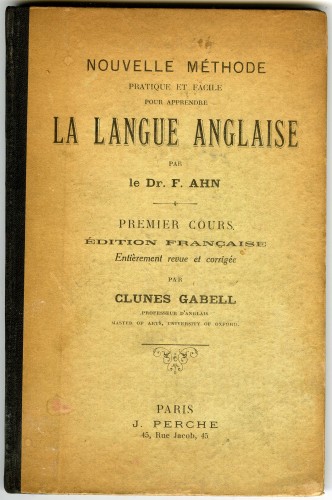

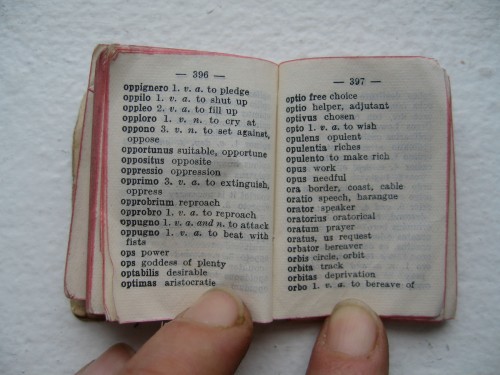

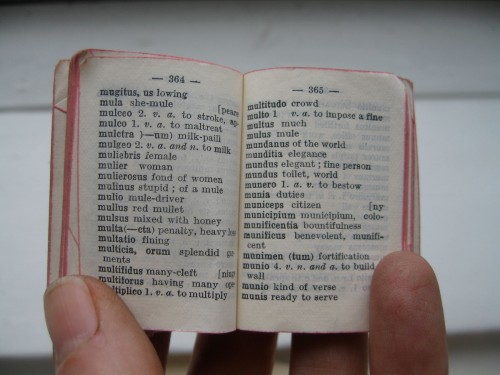

A series of dictionaries and grammar books that mark the stages of my mother Resia Schor‘s immigrations from Poland to France to America.

Polish French Dictionary, c.1937

English Language manual acquired in France c.1940

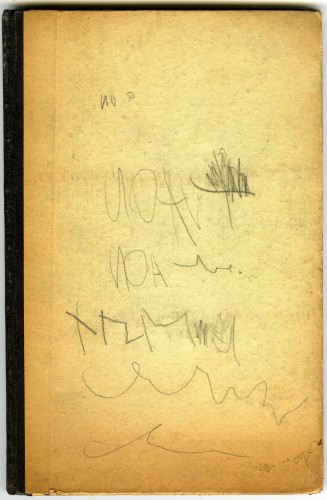

Back of same language manual, with what appears to be my sister's early efforts to write her name, NOA for Naomi, or Noemie, or Nomi, all variants of her name, c.1947

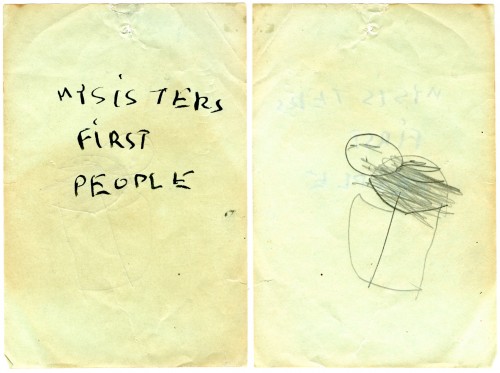

An early drawing of mine saved by my older sister Naomi.

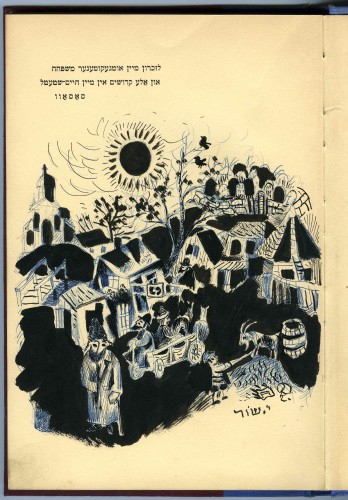

No book could be safely shunted off to the side to be given away or thrown out, even if in a language I can’t read, because my father Ilya Schor drew and painted on any and every surface.

Ilya Schor, ink and gouache drawing, inside of the cover of Yiddish-language poet Nakhum Bomze's "A Chasine in Harbst" (A Wedding in Autumn), Marstin Press, NYC, 1949

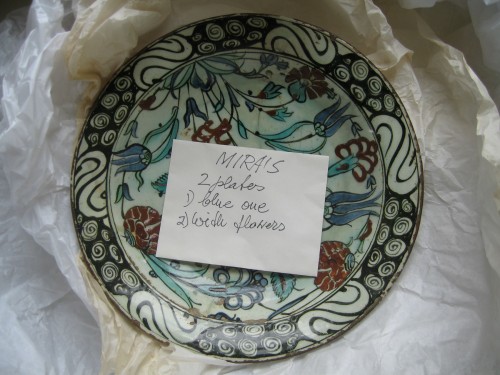

The day after the movers had emptied the apartment, I returned to pack the contents of one last shelf in one last closet, some left-over antique ceramics. I was exhausted and unprepared to encounter, though not for the first time, a message in time from my mother, from when she had two daughters and was always careful to give us each equally.

Thinking she would be survived by her two daughters, my mother marked various objects with my name, having already given my sister an equivalent gift

And finally the last thing to be packed was a small, heavy, glazed ceramic orb.

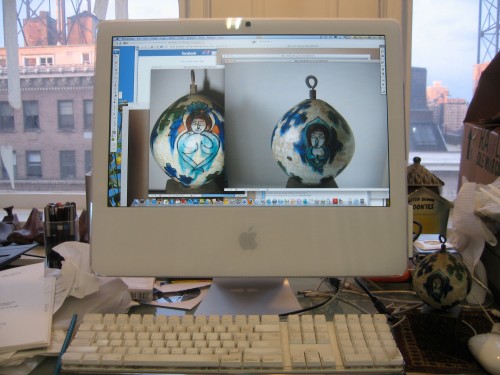

I barely had time to look at at it but it was both strongly yet only vaguely familiar, and the combination of spherical shape, glaze, and weight in relation to size made it memorable.I called it Orbis Mundi, its Christian markings suggesting a Latinate name. Orbis Mundi does in fact mean the sphere of the world, but although I was certain this must be a term from liturgy, it isn’t, I made it up.

The very day I moved in I set up my computer and connection to the internet. Sine qua non. Then the very first object I looked for as I started to open boxes was my little Orbis Mundi, which I found immediately.

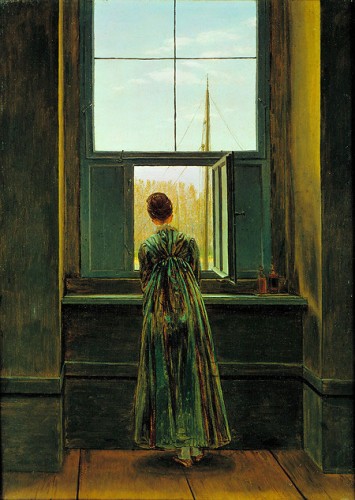

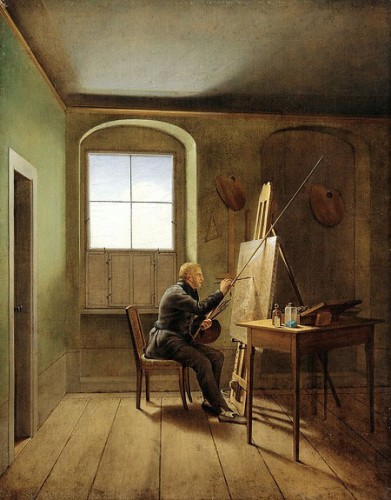

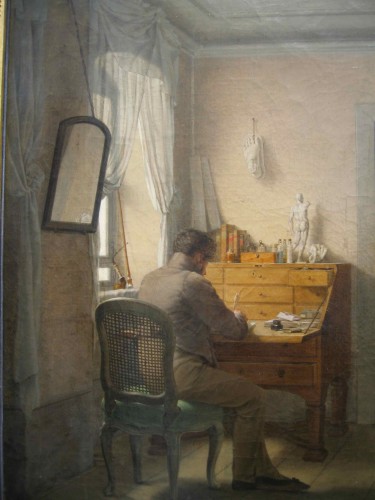

I have begun to make enough headway in unpacking, though my studio will be the last to be cleared and functional, that I’ve started to go out and see some art again. Last week I went to the Met to see Rooms with a View: The Open Window in the 19th Century –A Year of Positive Thinking four star recommendation: a modest show of small scaled modest paintings in the sense I think of the term, small paintings of domestic interiors, but painted with rigorous precision and abstract fluidity and a kind of formal clarity anticipating modernism given the window’s rectangularity as a central focus of each painting, with fascinating and occasionally quirky views of spare studio interiors, and with the liminal space of the open window as a framing device for the world outside, and a metaphoric reflection for the meaning of light, the safety of shelter as well the subtle imprisonment of domesticity. My current immersion in interiors made the show especially affecting.

As I left the museum, I chose the right hand path towards the lobby and exit, going down the hall with vitrines filled with early Christian antiquities and immediately spotted my Orbis Mundi! Or at least the Met’s larger and in far better condition version, though its markings are identical to mine. It turned out I was right in its having some relation to the Church, but not exactly in a liturgical manner: my little ceramic egg turned out to be a kind of 17th century Armenian version of Combat, hung to keep bugs and vermin from falling into oil lamps hanging in churches!

Knowing that this year would be disrupted by my move, I always intended that A Year of Positive Thinking would run longer than a year. The Year is a metaphorical time frame, a space of challenge to focus on art that I love while underlining the positive aspects of negative thinking, and so it can continue for a baker’s dozen of months, or as long as I am interested in doing it.

That the first object I fix on as I start to think about how to turn my family’s things into something that among other things is a Jewish story turns out to be a Christian Church accoutrement is not a contradiction to me: my parents owned it, because it pleased them as an object. And so it is the egg that I celebrate this Easter and last days of Passover, as I sit at my computer, that other Orbis Mundi, as I start up the blog again.

The worlds, April, 2011, photo: Mira Schor