I will complete the third part of “Wonder and Estrangement: Reflections on Three Caves” with a consideration of Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert, currently on special view at the Frick Museum, soon, but not yet. I am compelled to interrupt that thread with another one, about criticality and some current conditions of writing and publishing, particularly on the web (this is projected as also a three part thread). My regret at interrupting a “positive” line of thought, one that is about some artworks I love and that is not polemically driven, with one about criticality is tempered by the fact that this kind of interruption, caused as it is by competing directions of thought in a fast moving discursive atmosphere, is a component of some of the conditions of writing for the web that I will discuss in this new thread.

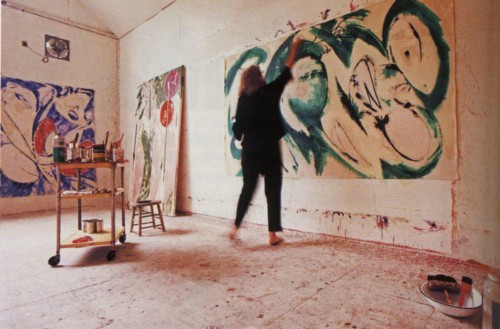

I am currently in what passes for my “desert,” that is to say the one place and time in the year when I am lucky enough to be able to retreat from the fray of the world into the life of a studio near the sea where with the least distractions from daily duties and professional obligations I can struggle with my work during an intense few weeks. I can’t count on revelations from any deity shining down on me from stage right, just the few hard-won moments of deep engagement with my work that make it possible for me to survive the rest of the time. But, just as in Bellini’s painting, where not just the beneficent signs of civilization signaled by the tiny shepherd and his flock in the middle distance, but also the fortifications of various small city-states set on various Tuscan hilltops beyond are clearly visible from the rocky encampment where St. Francis receives the stigmata from an unseen divine force, the voices of the world beyond my studio intervene daily, though with far less divine purposes or effects.

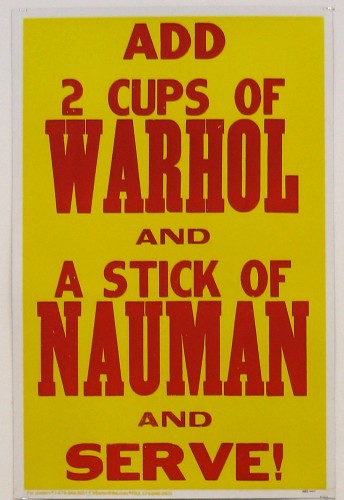

Today, for example, the desperation of some and exasperation of others commenting on one of my posts about Obama and the debt ceiling fiasco on Facebook makes me want to write a longer note there so part of my brain is occupied with that. Meanwhile I also want to publish the following A Year of Positive Thinking blog posts about writing this week so they are online in the time frame of Arts Writers Convening , a conference to be held this coming week in Philadelphia sponsored by the Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant Program (whose generosity helped me start this blog). In keeping with the paradox of St. Francis in the Desert, I have with regret chosen to not attend the Arts Writers conference because I so need these irreplaceable few days of the year that I can devote entirely to my own work, yet I still have in view these exterior markers and schedules while, as I will discuss, being perfectly aware that few if any may read my words in the right or indeed in any time frame.

Invisibility and Criticality

One evening in the 1990s I was walking down LaGuardia Place and ran into Leon Golub as he was putting out the garbage. This was some time after we had both been on a panel at The Cooper Union, “The Erotics of Painting,” organized by Lenore Malen, (May 6, 1992), during which I had made mincemeat of a critic who currently writes about art for a legendary weekly journal. I’m told that during my remarks Hans Haacke nearly fell out of his seat laughing and Brice Marden, who was sitting next to me on the panel and had just read four or five cryptics words that he had written on a napkin, something like “beauty…space…” (and I mean, only those few words), turned his head suddenly as he realized something unusual was going on (my comments from that panel are published as “The Erotics of Visuality” in my book Wet).

The evening after the panel Leon had called me up and said, “now, you’re a player.” Beyond being absolutely thrilled by his attention I think I was also slightly alarmed. I can’t retrospectively be sure what I thought. I can’t be sure if I really understood what it meant to be a player. I certainly thought I did and wanted to be one, but judging from my whole career to date and from a recent art document I will soon discuss here, I would hazard a guess and say, not really. But Leon was hopeful for me and during this chance encounter on the sidewalk in front of his house, in discussing this further, he said something to the effect of, “it’s good, you should attack as many important people as you can.” His vivid eyes gleamed as he relished the prospect of any valiant battle which he also apparently felt was a path to success or, indeed, a kind of power, although he knew as well as anybody how difficult and frustrating that path was (why won’t this show come to MoMA? [MoMA lists 9 works by Golub in its collection, however all are prints, they do not at present seem to own a major painting]).

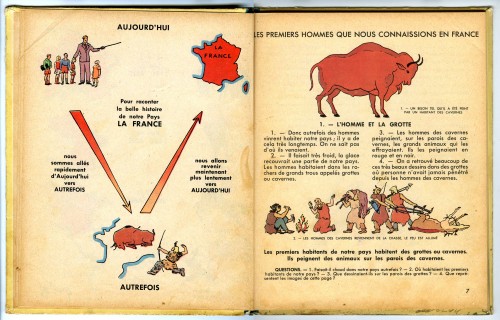

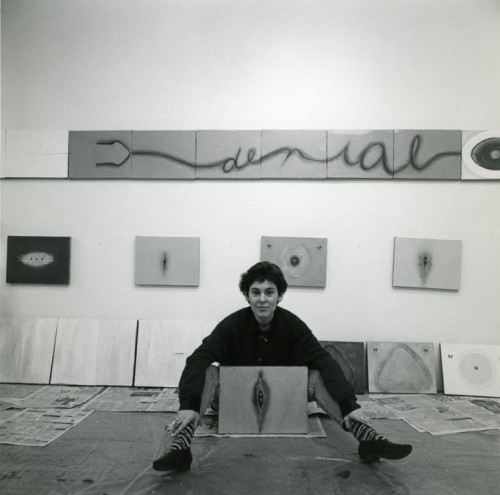

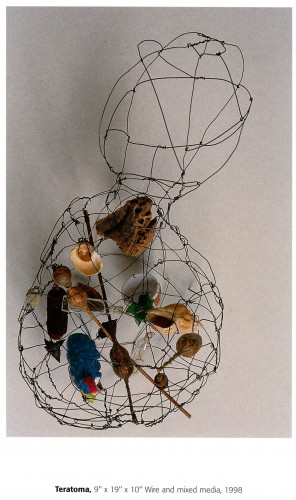

Leon was a great painter, and a great, indeed a necessary man, he is much missed. It was a privilege to know him at all and he had been very supportive of me, of M/E/A/N/I/N/G, and of my co-editor the painter Susan Bee. However his predictive powers as to my being a player were a bit shaky: I had already at that time and have since then attacked my share of powerful people yet, in one of his recent visual/textual analyses of who is who and what is what in the artworld, “A Biased and Incomplete Guide to Some Critics in New York (where I live and make art),” William Powhida gave me the highest rating on the criticality factor–95 out of 100–and the lowest on the visibility scale–5! Powhida’s amusing piece came out during the time I was involved in the major move I’ve described on this blog in the post Orbis Mundi so that I was unable to address these ratings until now. So here now are a few thoughts on criticality and visibility or the lack thereof.

For a more legible view click on the title link above

First of all, a belated thank you William Powhida for the kudos…and the visibility!

And secondly, before I say another self-serving word on the subject (reader alert!), note that Powhida has set the bar for criticality pretty low– “Criticality: arbitrary # based on word count, description, register, analysis, news items”– so it would seem that you don’t have to be a new Adorno to make a high grade, pretty much any text which is not a direct press release and has some content other than entirely gossip- or market- related would seem to apply to one’s criticality score.

It is symptomatic, or syndromatic perhaps, of the power structure of the artworld, really of any power structure, that I have addressed this issue before, notably in my February 14, 2006 lecture at SVA, “The Art of Nonconformist Criticality,” as well as in “The White List,” written for M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online‘s 2002 issue “Is Resistance futile?,” so that not only can I refer to my previous writings and lectures, but I might as well do so because they are relevant to the discussion at hand, including the reflection that for the most part no one remembers what anyone says enough for such self-cribbing to be a problem.

That I have to bring these up is only to state the obvious that the point is, and the point that I make in these texts, that the easiest way for power to deal with non-conforming criticism is to ignore it. Whereas, to use Guy Debord‘s terms, in the Soviet/Fascist epoch of the “concentrated spectacle,” power felt that it was necessary to literally disappear the inconvenient person by killing them and erasing their image from a photograph (China remains in the antiquated Soviet model, putting dissidents in jail and even making Googling the word “jasmine” or selling jasmine branches a crime for fear of contagion of the so-called “jasmine revolution” started in Tunisia this winter), or, under McCarthyism, blacklisting them from employment or access to an audience, in the “integrated spectacle” of free-market global capitalism, extreme rendition and Patriot Act aside, power can simply follow the golden rule of ignoring something entirely. Only what is visible is important, and if it isn’t visible it can’t possibly be good, and what has thus been rendered invisible must at the same time be bad and most likely does not exist.

I named this most effective weapon for silencing alternative views “The White List,” a less violent or visibly oppressive version of “the Black List.” Let me take as an example my first published essay, “Appropriated Sexuality.” In “The White List” I note:

My essay on David Salle, “Appropriated Sexuality,” was published–because Susan and I started our own magazine instead of accepting the status quo and getting depressed! Although overall I can’t complain about getting my writing published, nevertheless my ideas have encountered a subtle form of resistance. Thinking about the “blacklist,” I realize that what I am up against is something that doesn’t have a name. I’ll call it the white list. The white list not only makes it difficult to get alternative points of view published or exhibited, but even if you can get the work out, you still don’t get referenced or credited. After “Appropriated Sexuality” was published, people who I knew had read it wrote articles about Salle in which they would say, “some feminists say” or in some other vague way suggest that there were dissenters to the party line, but they would never actually provide a factual reference. The first favorable mention of this essay appeared in a 2002 Art in America book review by Raphael Rubinstein of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism–a full 16 years after the original publication of the Salle essay! Thus, the nonconforming point of view can be taken out of history.

Actually, Rubinstein‘s was more or less the first mention of this essay at all, and for all I know the last.

In fact part of what makes the white list so effective is that it is itself invisible (the black list was hush-hush in that people were too afraid to even speak about it openly for fear of being suspected of being “fellow travelers,” but it was only semi-obscured, people spoke about it with fear, in hushed tones, public hearings/American version of show trials were held, names were placed on actual black lists, people were imprisoned or forced into exile and eventually even network television news found its conscience).

In “The Art of Nonconformist Criticality” I go into further detail about the Salle essay because it marked my entry as a “player” into the critical field:

I started writing in the early 80s when I observed major changes in art and art theory, a reversal of attitudes about studio process, and of values about feminism, which had just barely had a decade to develop into art. These changes were epitomized for me in the work of someone I had gone to art school with and who was suddenly extremely successful financially and critically, that is, David Salle. No one was writing what I thought, although they might have been saying it in private. So I started to work on an essay eventually entitled, “Appropriated Sexuality” about the misogyny of the depiction of women in Salle’s work and the complicity of the critical apparatus that supported him.

I began with no ideas about publication. But as the essay came into its final form over a period of two years, I began to send it around, to other artists and to various magazines. It was the subject of many letters of rejection from both mainstream and high academic journals that were quite informative about the parameters of art writing. At one point, it was actually accepted for publication by a middle stream regional art magazine, but dropped at the very last minute. Meanwhile my manuscript had been shown to another writer who then published in the same journal a more wishy-washy text in which my ideas were vaguely alluded to as “some feminists say”, a typical example of the kind of balanced writing that is very common in much mainstream media and whose true agenda is the devaluation of opposing views. So that was Karybdis. A thoughtful rejection from October taught me one of the principal methods society deploys to deal with resistance: they tell you that are doing something wrong, even if you’re right. They didn’t like Salle anymore than I did but the enterprise of critiquing him must be approached with “great caution.” My error was in focusing on his representations of women because that was based on an erroneous essentialist premise that such a thing as “women” could still be considered a viable category (as opposed to the theoretical point of view that “women” was a social construct), whereas from their point of view the real problem was not what he was painting, but that he was painting.

I will freely state that the Salle article started my public life, setting me on the dual path of painter/writer I have been on since, so that in some way whatever visibility I have may stem from that initial act of criticality, in keeping with Golub’s advice. (And I will parenthetically state that obviously there is a complication here: the visibility I seek is a dual one, artist/writer, but in this I am not alone and I have powerful predecessors in such polemically inclined visual artists/writers as Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Smithson, Adrian Piper, and Mary Kelly, to name just a few of many significant artists/writers).

However what I didn’t fully realize and still find hard to believe, though it is most likely one factor in the nature of my “career,” is that Salle had powerful friends and adherents and they surely did nothing to help me, if they did not go out of their way to harm me. I’m not a Pollyanna but I tend to find it hard to believe that people actively do bad things on purpose, although I know that many people who are interested in power do exactly that all the time. Nevertheless I began to realize that something had been going on when on two occasions in recent years, long after the publication of that essay, powerful men of my acquaintance in the art world made the casual (but dead serious) assumption I was “tearing up” or “ripping up” something in whatever work I was doing now. The first time was about 20 years after the publication of the Salle ssay: I was having a lively conversation about something completely different with someone at a party when one of Salle’s friends came up to us and said with a shark-like grin on his own face, “Who’s she ripping up now?” And then again just last year, I mentioned to an eminence grise of the New York artworld that I had a new book coming out (A Decade of Negative Thinking) and he said, “Who are you attacking now?”

Esprit de l’escalier: I should have told him.

[And I haven’t even talked here about my calling some of the editors of October “aesthetic terrorists” (!) at a time when they had more real power than they may have now, as the critical organ of an aesthetic program shared by an international institutional network including major galleries and museums.]

You’d think that a reputation for critical ferocity would be a good thing, from let’s call it a business point of view. Speaking of October, a number of its editors and authors over the years, some of them initially Clement Greenberg’s disciples, have been thought of as art world Savonarolas, and that level of very serious but also often exclusionary criticality gave some of them power in part because they managed not just to be critical but to arrogate to themselves ownership of the correct language of criticality itself. And it was, for better and worse, part of the Clement Greenberg legend, but perhaps because he had most importantly backed a couple of the right horses, Jackson Pollock in particular, his criticality had the positive potential monetary value of a good stock tip, despite its destructive side–telling artists what they should or shouldn’t paint, dismissing all art with so-called literary content, and in later years being a bit of a caricature of himself, siting around with a scotch in his hand saying that’s not a good picture. At some point and for a long while, he could make artists in the market and he could break artists in their studio, a power I obviously do not have and don’t seem to have sought out despite my alleged propensity for “ripping people up.”

So who you attack, on what theoretical grounds, as well as who you back or are associated with, and how interested you are in power, all matter and Golub’s advice that I attack important people has had limited viability in terms of developing visibility. A tree can fall in the forest but those trees around it who are interested in power can determine that they will not give that particular tree the power of their admitting that they heard it fall.

At least for me there seems to be an inverse relation between criticality and visibility. I think this was Powhida’s point in including me in “A Biased and Incomplete Guide to Some Critics in New York (where I live and make art),”.

Coming next: The Imperium of Analytics