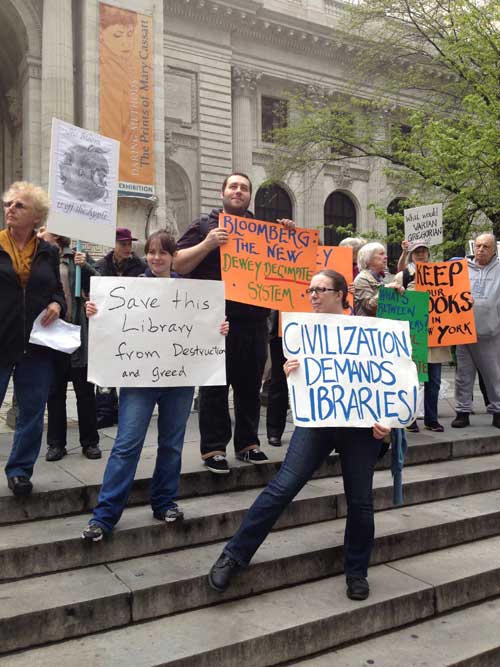

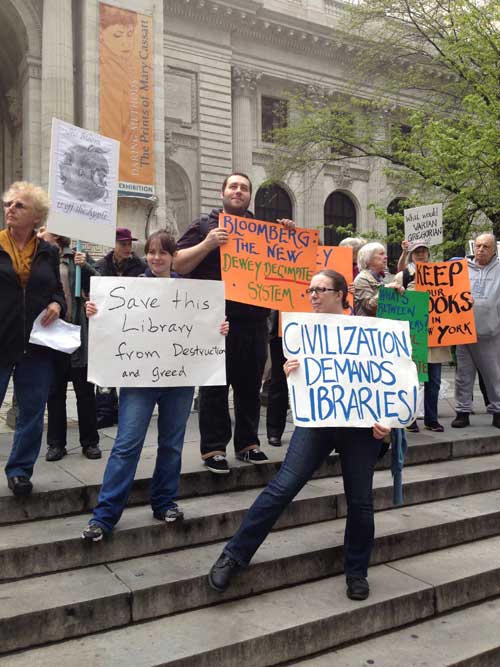

Where the fuck was Joan Didion? Where was Edward Albee?” That’s what I thought this afternoon, when after about an hour or so, I decided I could do at least one iota more for the cause that had brought me out of the house on a rainy day by writing something about the tiny demonstration I participated in at the New York Public Library, organized by SAVE THE 42ND STREET LIBRARY-The Committee to Save the New York Public Library to protest the planned destruction of the guts of the New York Public Library main branch at 42nd street, than by standing around with a motley crew of mostly more elderly than me ladies and gentlemen, a few of them using personal mobility vehicles, plus perhaps some 20 young people, holding hand-made signs up to for the most part uncaring passersby, with no media in attendance while I was there at least. People passed by the demonstrators, going in and out of the library, and probably some were annoyed that it was a bit harder to get their pictures taken with the lions because there were people hanging around with signs.

The occasion for the demonstration was a meeting of the Board though the few people holding up signs near a side entrance for vehicles saw few limousines pull in, if any.

For some of the details of the plan, here is some text and links from the Save the New York Public Library website:

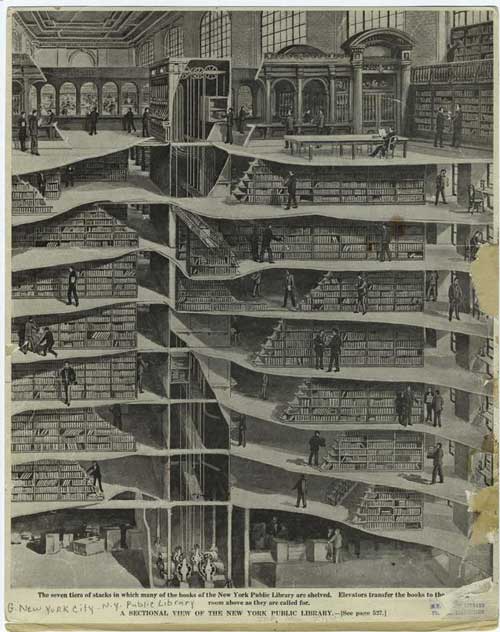

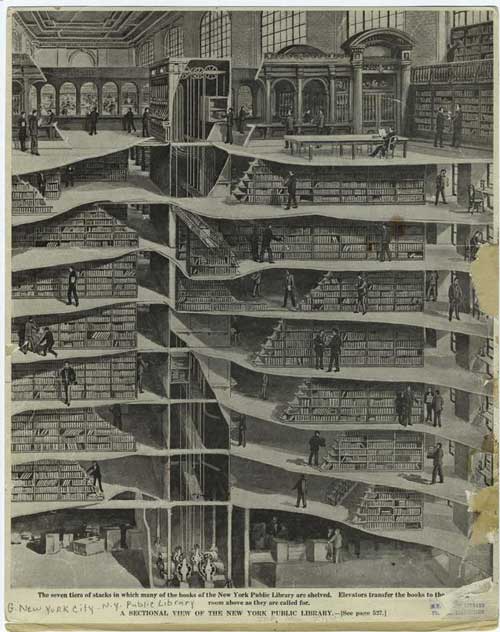

The Central Library Plan (CLP), at enormous cost to New York City and its taxpayers, would irreparably damage the 42nd Street Research Library – one of the world’s great reference libraries and a historic landmark. The CLP would demolish the library’s historic seven-story book stacks, install a circulating library in their stead, and displace 1.5 million books to central New Jersey. The new circulating library would replace the Mid-Manhattan Library (at 40th and 5th Avenue) and SIBL (Science, Industry and Business Library, at 34th and Madison), which would both be sold off.

• It will be hugely expensive, costing a minimum of $300 million (probably much more), of which $150 million will come from New York City taxpayers. There is great concern that the Library’s focus on a highly-complex construction project will absorb desperately-needed funds which might otherwise pay for renovations of branch libraries, and replenish slashed curatorial and acquisitions budgets.

• It will radically reduce the space available for the Mid-Manhattan and SIBL.

• It will threaten the 42nd Street Library’s status as one of the world’s great research libraries.

• It will threaten the architectural integrity of the landmarked 42nd Street building.

• It does not take into consideration more efficient and less destructive alternatives, such as combining SIBL and the Mid-Manhattan into a rehabilitated and expanded building on the Mid-Manhattan site.

Underlying the widespread concern is the closed process through which the Library administration has made its decisions. Despite the fact that the 42nd Street building is owned by the city and is one of our most iconic structures, the plan was formulated with minimal public notification and no public input. The $150 million that the city has earmarked for the project was awarded without oversight by the City Council and with no public hearings. If alternatives have been considered they have never been disclosed, and no cost-benefit analysis or detailed budget has ever been presented.

Famed architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable, writing in the Wall Street Journal, attacked the Central Library Plan as “a plan devised out of a profound ignorance of or willful disregard for not only the library’s original concept and design, but also the folly of altering its meaning and mission and compromising its historical and architectural integrity. You don’t ‘update’ a masterpiece.”

New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman derided the design for the new circulating library which would replace the book stacks in the 42nd Street building as having “all the elegance and distinction of a suburban mall,” and called it an “awkward, cramped, banal pastiche of tiers facing claustrophobia-inducing windows, built around a space-wasting atrium with a curved staircase more suited to a Las Vegas hotel.”

It seems a venture whose financial premise is patently suspect, and an outrage to civilization. Also this seems like a very poor idea in terms of a positivistic belief in technology, since by the time the plan to irretrievably remove the stacks of books from the core of the library to make way for internet facilities is realized, such technology may already be outdated, as everybody knows who struggles with constantly changing digital data storage formats and devices).

Other informative links include:

http://www.change.org/petitions/president-marx-reconsider-the-350-million-plan-to-remake-nyc-s-landmark-central-library

“Upheaval at the New York Public Library,” (The Nation, November 30, 2011)

“The Battle Over the New York Public Library, continued,” (The Nation, April 19, 2012)

“The Fight to Save the New York Public Library” (The Nation, June 18, 2012)

But today’s demonstration broke my heart. I applaud the futile efforts of the save the library petition organizers. But didn’t they know any writers? Wouldn’t this be the time to get Joan Didion or Edward Albee out of mothballs, get any living Pulitzer Prize winners in any field that requires looking at a book to get their asses out there to say a few words and get their face in the New York Times. I had imagined a gathering of some major authors, the few writers who qualify as marquee names in America and could get some press–Edward Albee, Joan Didion, Philip Roth–why am I thinking of so many writers in their 80s? Maybe because they are among the last hold-overs from when literary stars were bona fide celebrities. Norman Mailer couldn’t make it, he is dead. You know that if this were Paris anytime between the liberation of Paris and their deaths, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre would be at the front of a horde of French writers, journalists, and actors, if some assholes were trying to gut the Bibliotèque Nationale–well actually the French did something of a similar nature with the Bibliotèque National, leaving the original building intact but moving much of the collection to boondoggle high-rise buildings at the periphery of Paris, and at any rate de Beauvoir and Sartre were both dead by the time this took place.

OK, it did make the New York Times, a blog post this afternoon generously estimating the crowd of demonstrators at one hundred.

For that it’s worth, because all the famous writers in USA wouldn’t alter the plans of the worst folly since the destruction of Penn station and for what? and to serve who?

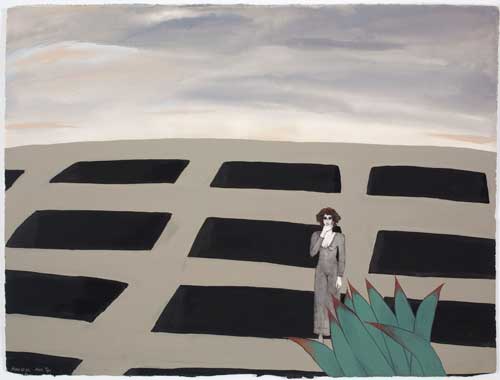

“They paved paradise to put up a parking lot.” Or a glorified Starbucks, in this case (the projected architectural renderings look better than that, but they don’t include the unnecessary and phenomenally expensive destruction that will take place, or what renovating the existing library branch across the street might look like for much less.)

This is a disaster in real time that is pointless and could be prevented, but no one who cares seems to have any power, and no one who has power cares.

I wrote a Facebook Note relating to the plans for the New York Public Library last June 12, 2012. In it I described a conversation I had with my friend Susanna Heller, who at the time was reading The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt, winner of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize in non-fiction, about Lucretius’ book On the Nature of Things, which she was also reading. She read me the following passage from The Swerve and took the trouble to type it up and send it to me:

Hypatia was the daughter of a mathematician, one of the Museum’s famous scholars-in-residence. Legendarily beautiful as a young woman, she had become famous for her attainments in astronomy, music, mathematics, and philosophy. Students came from great distances to study the work of Plato and Aristotle under her tutelage. Such was her authority that other philosophers wrote to her and anxiously solicited her approval. “If you decree that I ought to publish my book,” wrote one such correspondent to Hypatia, “I will dedicate it to orators and philosophers together,” If, on the other hand, “it does not seem to you worthy”, the letter continues, “ a close and profound darkness will overshadow it , and mankind will never hear it mentioned.”

Wrapped in the traditional philosopher’s cloak, called a tribon and moving about the city in a chariot, Hypatia was one of Alexandria’s most visible public figures. Women in the ancient world often lived sequestered lives, but not she. “ Such was her self-possession and ease of manner, arising from the refinement and cultivation of her mind,” writes a contemporary, “ that she not unfrequently appeared in public in presence of the magistrates.” Her easy access to the ruling elite did not mean that she constantly meddled in politics. At the time of the earlier attacks on the cult images, she and her followers evidently held themselves aloof, telling themselves perhaps that the smashing of inanimate statues left intact what really mattered. But with the agitation against the Jews it must have become clear that the flames of fanaticism were not going to lie down.

Hypatia’s support for Orestes’ refusal to expel the city’s Jewish population may help to explain what happened next. Rumors began to circulate that her absorption in astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy- so strange, after all, in a woman- was sinister: she must be a witch practicing black magic. In March 415 the crowd, whipped into a frenzy by one of Cyril’s henchmen, erupted. Returning to her house, Hypatia was pulled from her chariot and taken to a church that was formerly a temple to the emperor. (The setting was no accident: it signified the transformation of paganism into the one true faith.) There, after she was stripped of her clothing, her skin was flayed off with broken bits of pottery. The mob then dragged her corpse outside the city walls and burned it. Their hero Cyril was eventually made a saint.

The murder of Hypatia signified more than the end of one remarkable person; it effectively marked the downfall of Alexandrian intellectual life and was the death knell for the whole intellectual tradition that underlay the text that Poggio recovered so many centuries later. The Museum, with its dreams of assembling all texts, all schools, all ideas, was no longer at the protected center of civil society. In the years that followed the library virtually ceased to be mentioned, as if its great collections, virtually the sum of classical culture, had vanished without a trace. They had almost certainly not disappeared all at once- such a momentous act of destruction would have been recorded. But if one asks, Where did all the books go? The answer lies not only in the quick work of soldiers’ flames and the long, slow secret labor of the bookworm. It lies, symbolically at least, in the fate of Hypatia.

The other libraries of the ancient world fared no better. A survey of Rome in the early fourth century listed twenty-eight public libraries, in addition to the unnumbered private collections in aristocratic mansions. Near the century’s end, the historian Ammianus Marcellinus complained that Romans had virtually abandoned serious reading. Ammianus was not lamenting barbarians raids or Christian fanaticism. No doubt these were at work, somewhere in the background of the phenomena that struck him. But what he observed, as the empire slowly crumbled, was a loss of cultural moorings, a descent into febrile triviality. “In place of the philosopher the singer is called in, and in place of the orator the teacher of stagecraft, and while the libraries are shut up forever like tombs, water-organs are manufactured and lyres as large as carriages.” Moreover, he noted sourly, people were driving their chariots at lunatic speed through the crowded streets.