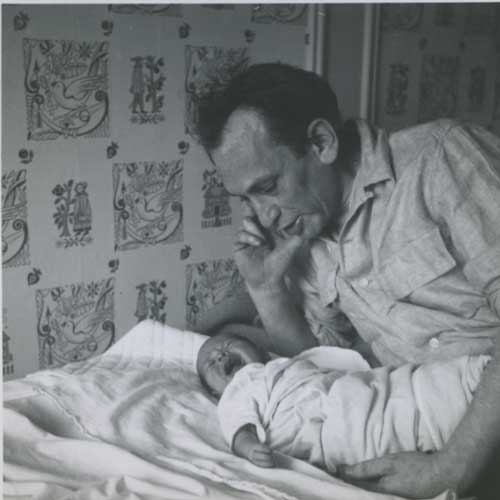

My father Ilya Schor died 59 years ago today, June 7, 1961, a week after my 11th birthday. Every year in the weeks preceding this anniversary, I experience a rise in anxiety, depression, paranoia even, always ascribing it to contemporary circumstances until the date is upon me. He was 57 years old, had been a heavy smoker from his teens until sometime before I was born, and basically died of cardiovascular failure of all sorts–though I always felt that in a time of better medical care he would not have died, but then my sister Naomi Schor died of vascular issues as well when she was 58, so who knows. His symptoms were misdiagnosed as anxiety but I also have written that because he had a succession of small heart attacks in the weeks after watching the daily broadcasts of the Eichmann trials, my sister and I had independently come to the same conclusion–he died of Eichmann).

This spring a few things happened in the weeks before this anniversary, related to my father’s life and work.

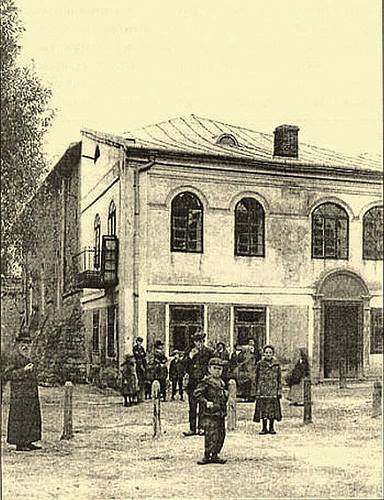

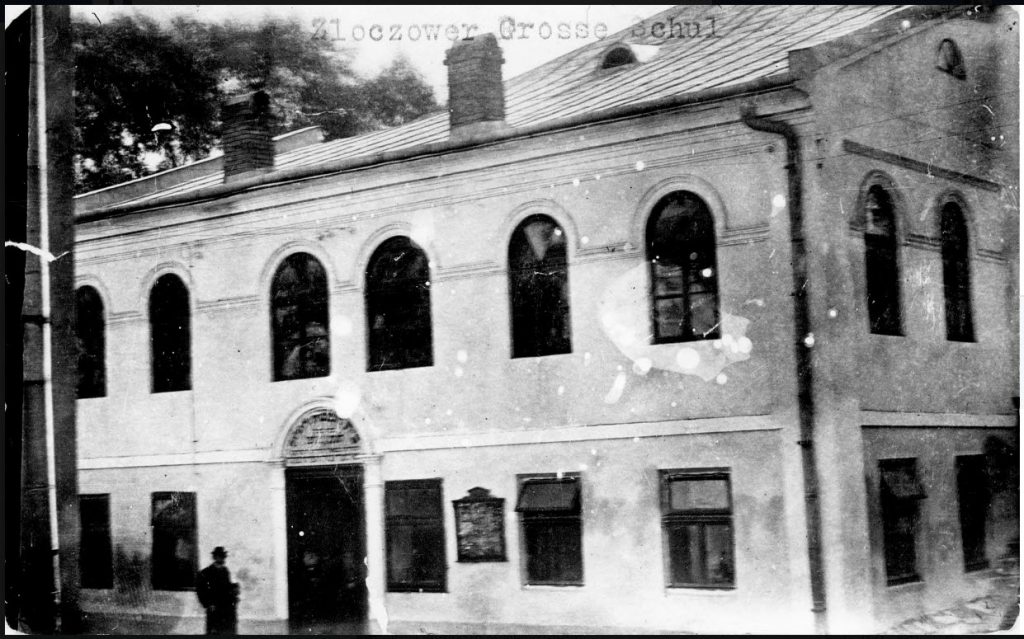

First, I was contacted by Shimon Briman, a journalist and historian from Israel, born in Ukraine, who has in recent years done a lot of work researching the Jewish community of the town of Zloczow, where my father was born and raised, a town which changed nationalities a few times, from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to Poland, to now the Ukraine, where it is referred to as Zolochiv (having spent my life remembering the Polish spelling with its characteristic surplus of consonants, I am not going to change how I spell it). He had many questions for me but also was able to answer questions I had about the nature of the town: I have always been confused by the semi-rural shtetl my father depicted and pictures of the town in the early twentieth century depicting a typical provincial Western city of that time period, with fine shops and hotels. In fact these two worlds were co-existent, as I have gotten fleeting intimations of before, but what I did not know was that it was a Jewish town, that is to say the bourgeoisie, the administration, all Jewish. He sent me pictures of the synagogue that my father often painted and of the rubble of the empty lot that exists now where it had once stood. I am glad my father did not ever see that empty lot. The Jews of Zloczow were murdered in the town in a succession of pogroms: there were no deportations to concentration camps, just slaughter in place.

Briman sent me a picture of the grassy field which was the cemetery–the headstones all were destroyed during the Holocaust, but apparently the human remains are still there. So the dust of my grandfather’s bones may lie there still. He has posted a touching tribute to my father with lovely pictures from the collection of the son of one of my father’s friends from his childhood.

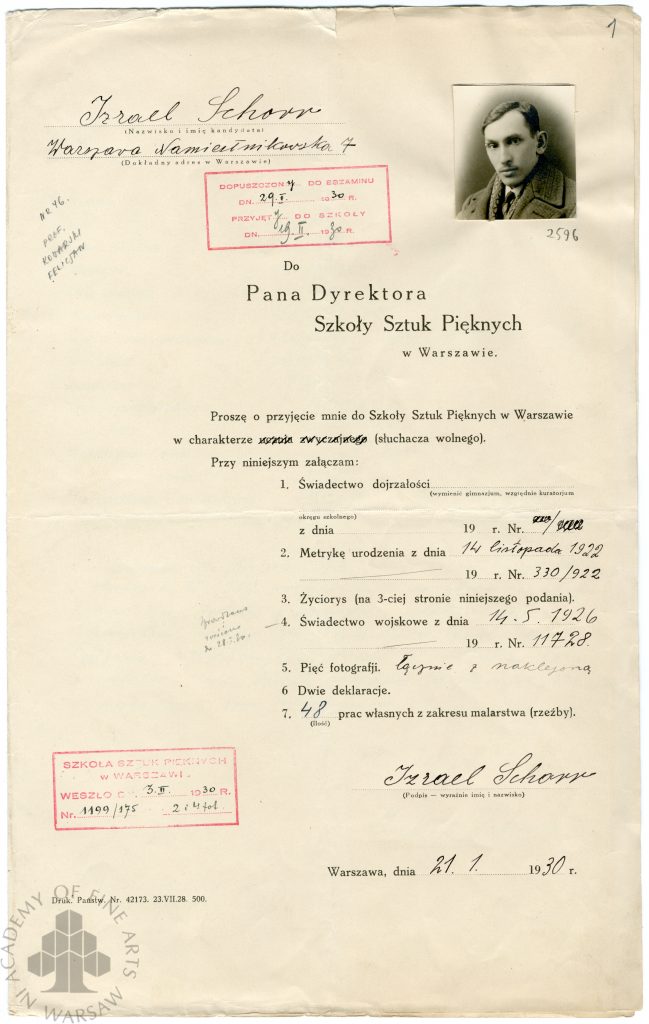

At around the same time I was contacted by a young woman art historian at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts who as part of an assignment to research women art students was interested in researching my mother Resia Schor’s career, having discovered her through some school documents in the Academy Archives. Through this connection I was able to obtain some of my father’s Academy documents. Here is one document from 1930 ((unfortunately I don’t read Polish so I don’t know what it says). In 1930, he was 26 years old. (He was renamed Ilya by a Russian friend in Paris in the late 1930s and that became his name when he arrived in the United States)

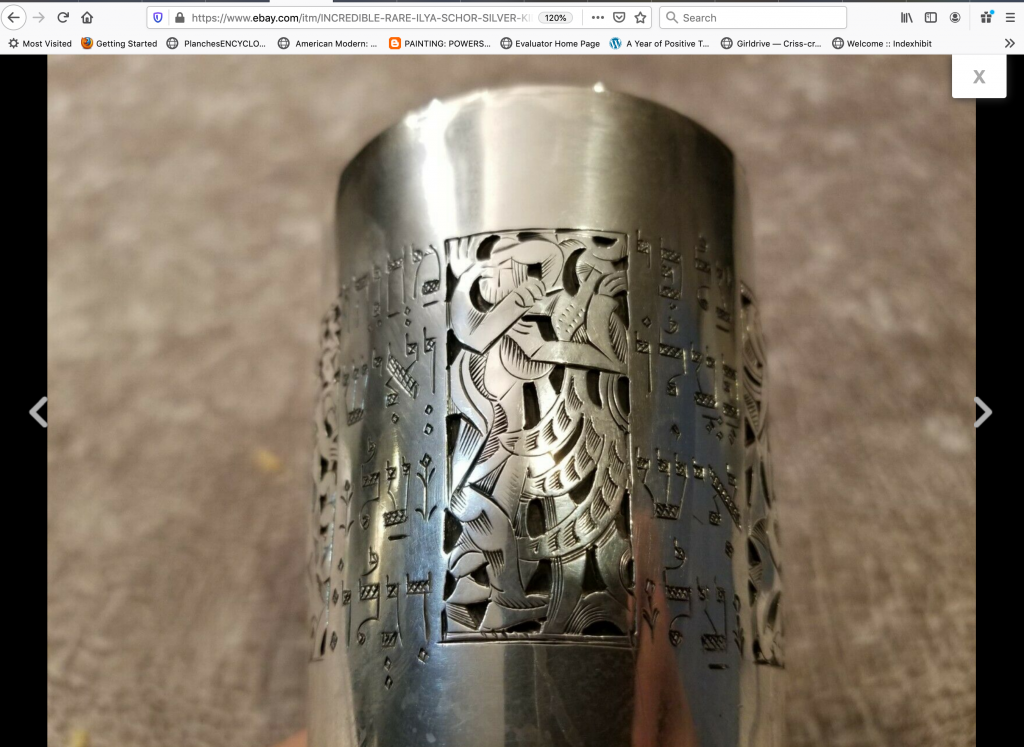

Next, I received an email asking me to comment on a work by my father. The query came in a neutral tone, without prejudicial wording, but I had a sense of what it was about and the minute I saw the pictures I understood what my task was. I spent the week before my birthday and the approaching anniversary of my father’s death meticulously trying to explain why I felt this work was a forgery–there are fake Ilya Schors (in the area of Judaica). My mother always said that my father always said if an artist is copied that is a real compliment, a testimonial to having a recognizable style! Some recent fake Ilya Schors I have seen are boldly improbable, bearing almost no resemblance and clearly, brazenly brand new, though with a faked signature. But a couple of objects that I’ve been asked to consider have been more disturbing., In these, someone with some skill has gone to quite a lot of trouble to produce a work that might pass–actually I literally mean one person seems to be responsible for some ambitious attempts, because I am now becoming an expert in this forger’s hand as well. I will post no pictures, obviously. In fact posting pictures of my father’s silver work is always a danger. But I have shared online (in a previous birthday post, from 2013) what I consider one of his masterpieces, in part because because I am fairly certain it was destroyed in a synagogue fire decades ago.

As I went over the pictures comparing them detail by detail to similar works I had complete verification of (and by the way I have learned that an artist’s estate cannot say that something is a fake because you could be sued, you can only say that you can’t verify), at times I wept because while, when I see one of the impostures, I experience a deep sense of injury to something at the core of my being, when I recognize the trace of my father’s hand in an engraved line into silver, I can feel him making it. As a child I watched him work. That was 60 or more years ago, so it amazes me to re-experience how much I learned at that time. It is a fully embodied memory of artistic gestures. When he was a teenager, before he went to art school in Warsaw, he had trained with a goldsmith and engraver, encouraged by his older brother Moses who thought the talented boy should learn a profession so that he could earn a living, a wise and as it turns out providential decision. He was extremely deft, swift, and certain in each mark. In engraving gold, silver, or hard wood, you cannot make a mistake. He also brought to each mark and flourish a particular joy coming from the culture of the pre-Holocaust Hadisim of Eastern Europe into which he was born. It is the character of this joy, suffused with humble piety and a kind of sadness, as expressed in silver and gold and in engravings and paintings, that makes his work unique and notable, and thus worthy of fakery.

That same week someone put up for sale, on eBay of all places, a truly exquisite Kiddush cup by my father, one that had been sold at a Judaica auction at Sotheby’s some time in the past thirty years. The price was ambitious, especially for eBay, so I am concerned about that, but I immediately saw/felt my father’s craft. But even though it has been on eBay so that some forger out there might be able to give it a go, I still am reluctant to share the screen shots I took of details. Still I will share just one, on the chance that my blog is obscure enough that no one with evil designs (literally) will see it.

As I have just celebrated my 70th birthday, I am concerned that once I am gone, there will be no one as qualified as I am to comment on the possible authenticity of an Ilya Schor work. I realized as I was comparing details between the real and the …what I think is not real work…that it is imperative that I leave a map of my reasoning, which may direct future art historians or art appraisers through my experience and visual line of thought. This is one more thing I feel that I must do as part of the cultural autobiography/biography of my parents’ life and work–“The Schor Project” as I call the work that I have not done except in small fragments such as this post as I struggle to achieve a place for my own work and to deal with the everyday. Each immersion in a detail of the past, each art work, letter, document, is an emotional journey that is difficult to recover from enough to meet the challenges of the present.

It is part of the myth of American exceptionalism that there is, that there must be closure, that there is a schedule for grief, that things can be put into the past and left there. Our current political moment is stark evidence that there is no such thing as closure, historically, or personally.