Passover is the Jewish Holiday with the most ceremonial and spiritual meaning for me, most likely because from my childhood into my thirties I was fortunate enough that my family was included in the Seders of David and Norma Levitt, dear friends and patrons of my father, Ilya Schor. In a way these were archetypal post-war American Jewish affairs, complete with Manischewitz wine and an uncle or cousin disappearing at some point to return in a white sheet as Elijah, handing out gold paper-wrapped chocolates to the children. I have no idea what my father thought of the style of these celebrations compared to the Seders of his childhood in the Hasidic community of Zlozcow, Galicia but I loved them and they were also, and grew more so in later years, scholarly and spiritual events. Even though at these events, without religious training and unable to read Hebrew, my sister and I were largely mute as others read, prayed and debated around us, nevertheless the Seder is the most meaningful holiday to me.My mother Resia and I began for the first time to do our own Seders when she was in her 80s and I was in my forties. We used a beautiful yellow and green service that my parents had bought when they traveled to Los Angeles in 1947 to visit my father’s family. His half brother Abraham had helped bring my parents to America in 1941, they met for the first time in their lives a few months a few months later. Abraham had settled in LA where his children were all in the film industry. By 1947 he had died but my parents with my sister Naomi then four years old took a long train ride across the States dipping into Mexico and back up to LA to stay with the family for a couple of months.

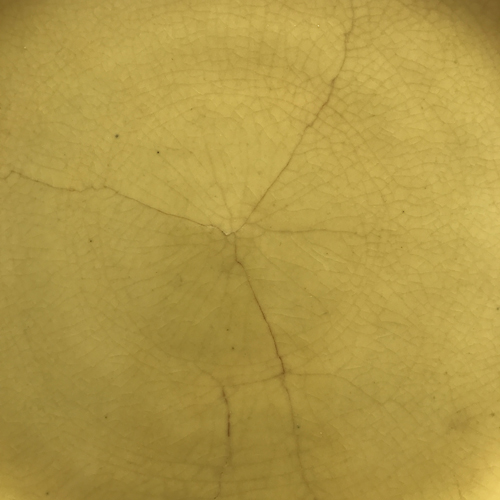

Over the years one of the dinner plates, pressed under the weight of the other plates stacked above it, quietly shattered while remaining whole. This glowing yellow circle with its cobweb of fissures brought about by the pressure of history and time is for me a self-portrait, a portrait of the Jewish people, and this year a portrait of the best of civilization itself.

At the beginning of the Seder because I know so little and have always forgotten the little I know, I read a Hasidic story from a book I found to help me lead as best I can a Seder:

When the Baal Shem Tov had a difficult task before him, he would go to a certain place in the woods, light a fire, and meditate in prayer. And then he was able to perform the task.

A generation later, the Maggid of Mazrich was faced with the same task. So he went to the same place in the woods, but he had forgotten exactly how to light the fire as the Baal Shem Tov had done. He said, “I can no longer light the fire, but I can still speak the prayers.” And so he prayed as the Baal Shem Tov had prayed and he was able to complete the task.

A generation later, Rabbi Moshe Lev had to perform this same task. He too went into the woods, but not only had he forgotten how to light the fire, he had forgotten the prayers as well. He said, “I can no longer light the fire, not do I know the secret meditations belonging to the prayers. But I do know the place in the woods to which it all belongs, and that must be sufficient.” And sufficient it was.But when another generation had passed, Rabi Israel Salanter was called upon to perform the task. He sat down on his golden chair in is castle and said, “I cannot light the fire. I have forgotten the prayers. I do not know the place in the forest. But we can tell the story of how it was once done, and that must be sufficient.” And sufficient it was.

Chag Sameach

Happy Festival

Happy Passover