A few works on paper that I did in the 1970s are going to be shown for the first time in Four Figures, a group exhibition curated by artist Tom Knechtel at Marc Selwyn Fine Art in Beverly Hills, California, opening Saturday July 12 through August 23.

These are part of a body of work from the mid-1970s in which the overall subject was interior language, or, coming from a more political, feminist approach, the idea that women are filled with language, rather than being empty vessels whose exterior nubile beauty as a commodity to be traded among men is the principal focus of their value in most societies.

I wanted to approach representation of women, and specifically self-representation as living inside a female body, with a mind, no longer from the point of view of figuration, whether realist or surrealist, which had been my first approach to representing myself as an agent in the world, much as a number of women artists associated with the Surrealist movement had done–I was already on that path even before I first saw works by Florine Stettheimer, Lenore Fini, Leonora Carrington, Frida Kahlo, and Dorothea Tanning, having found cultural permission for narrative and representation in the works of male Surrealist artists such as Max Ernst and René Magritte as well as from early Italian Renaissance and Flemish painting, Rajput painting, and Japanese emaki–but, now, from the point of view of an interiority of thought, with the image of language as the sign for thought.

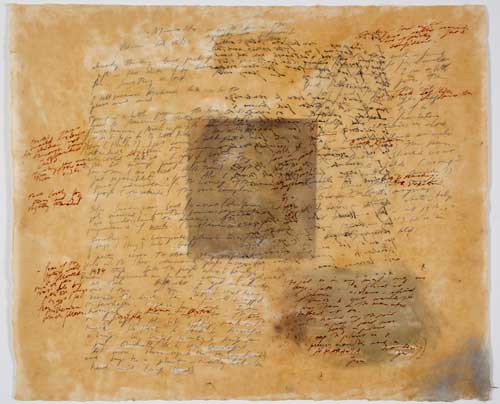

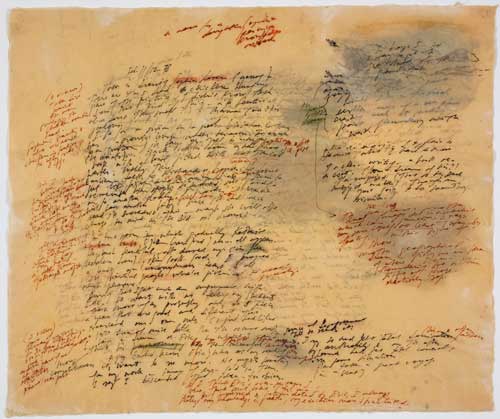

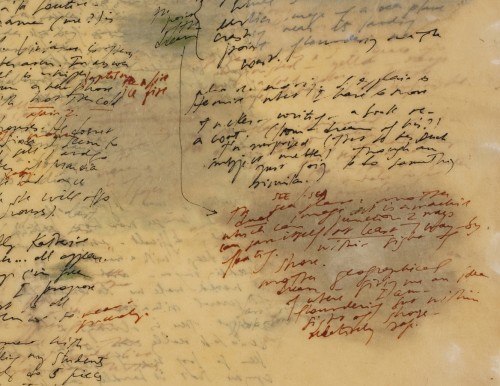

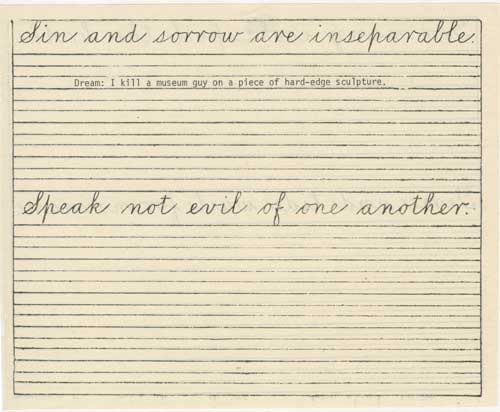

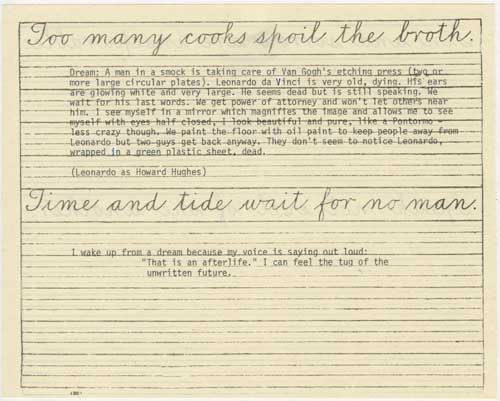

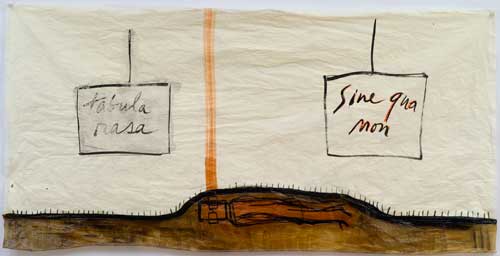

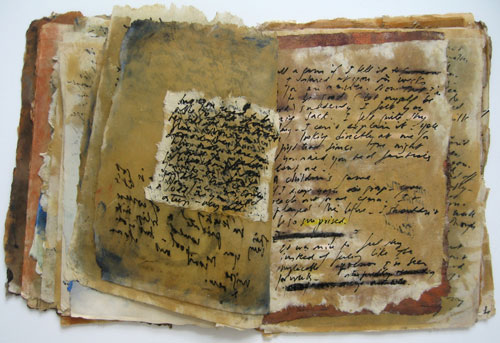

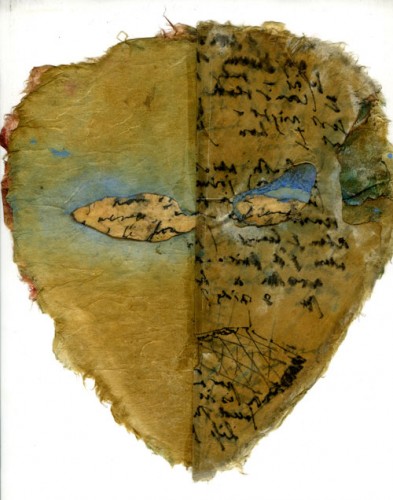

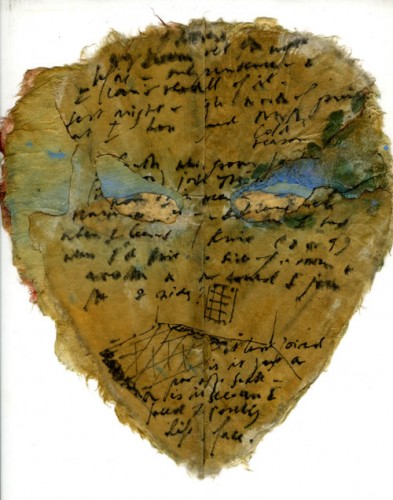

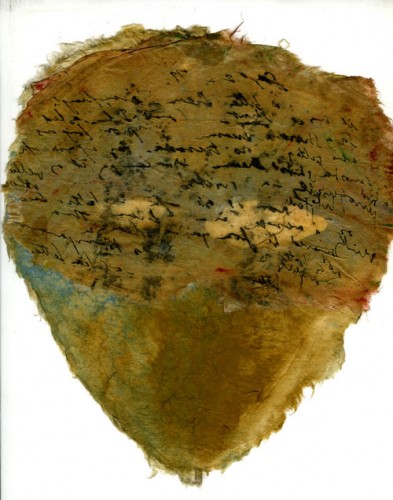

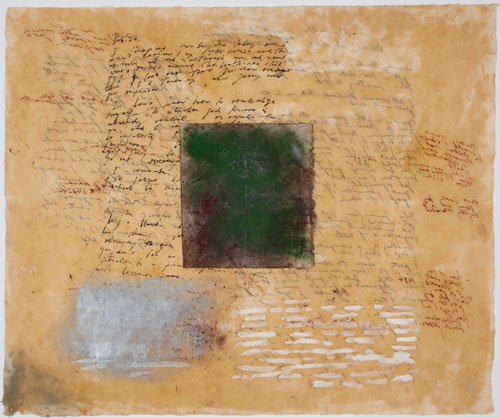

There were five groups of work done between 1976 and 1978: the first were a group of unfolded or folded fan shapes covered with handwriting, followed by a touchstone, foundational work for me, Book of Pages in 1976, followed by a group of masks many of which kept the idea of the book so that the mask has several layers, as did a series of Dress Book pieces, and finally the Dream series, in which the image was the text of a dream handwritten in black ink, with my interpretation and associations in sepia ink. While the shapes changed accordingly, the “image” on the surfaces was my handwriting recording dreams or diaristic personal writing and in some cases directly addressing a specific person, a much bemused male muse. Some works also incorporated diagrammatic drawings. All works were made from hand-made Japanese rice papers, some diaphanously delicate and made translucent with Japan Gold Size medium which also fixed the dry pigment I used for color used as matter rather than illusion, some other paper richly fibrous and sturdy.

All the works were two-sided: each component or piece of paper was worked from both sides so that the “front” was created by material applied to the “back” in order to create the effects that underlay the writing in the “front” but in the process the brute instrumentality of the work on the “back” often ended up trumping the more intentionally produced “front,” bolder and more abstract. Because the paper was often translucent, text could be doubly difficult to decipher: my handwriting was inherently difficult to read, and some of the text that was foregrounded was backwards, with the legible face permanently inaccessible to the viewer.

Since many of these works continued to work with the format of a book of pages that could be turned, these works were also layered dimensionally, you could turn the pages of the woman, her dress, or her face (where you might also try to lift a veil) and try to “read” the woman, but I came to writing as image at the moment when I saw that my handwriting had achieved an abstract beauty that was unrelated to easy legibility. Even the Dream pieces, one of which is in the Four Figures exhibition, though flat, were not only reversible, but sometimes contained a shape sandwiched within layers of paper so that what you thought might be revealed if you turned the piece over never actually surfaced.

These works were difficult to categorize: though I thought of myself as a painter, as I had earlier when working with gouache on paper, in defiance of the rules left over from Greenbergian formalism in the New York School that made oil or acrylic on canvas the probative medium, these were not paintings. But though they were objects they were neither conventional sculptures, nor could they be folded into any type of avant-garde sculpture focused on the readymade. The use of ink on paper made them drawings, but aside from the occasional diagrammatic sketch, writing escaped back into the category of actually being writing, not drawing. Because the writing was personal, the private made public yet retaining its illegibility, and because the image was my handwriting as opposed to printed text as many conceptual artists used at the time and rather than being writing that was meta-generic, in the manner of Hanne Darboven‘s (or Cy Twombly’s) scrawls, and because they did not turn their back on visual pleasure, they were not dematerializations according to the interpretation of that term as codified at the time. They were materializations of thought.

They were things, intensely personal things, that for the fullest understanding and apprehension, had to be experienced not just optically from a respectable spectatorial distance but viewed/experienced by an individual, pages turned, a veil lifted, a work turned over in your hand, with perhaps a grain of pigment or even a trace of the aroma of the medium remaining with you as material traces.

Thus, though they were things, and even quite precious ones, rare and fragile, they were the opposite of art commodities. They were and are still best experienced by hand but practically for their protection they require special handling and framing, thus are hard to exhibit to the fullest extent of their meaning (in Four Figures for clarity of presentation and their protection a number of works from this period are assembled together under Plexiglas and thus only one view of each work is available, other solutions include two-sided frames or the treatment accorded rare manuscripts, in a vitrine, open to a selected page, occasionally turned).

Because of their basis in feminist desire for alternate representations of the experience of being a woman, because of their focus on language as subject and image, because of their interest in scale through accretions of modules (in this case pages), because of their seriality (though this was narrative rather than in relation to mechanical reproduction), and because of their thingness yet impracticality, making them both experiential and notional, they have always seemed to me like archetypal 1970’s art, feminist and otherwise.

*Works reproduced include a view of Book of Pages, 1976; and from the exhibition Four Figures, three views of Mask Book: Floor Plan, September 2, 1977, ink, dry pigment, Japan Gold Size medium on rice paper, front with page closed, page open, and a view of the back, which will not be visible in the exhibition; and Dreams, February 25-26, 1978, ink, dry pigment, Japan Gold Size on rice paper, c. 18″x29,” image of the side that will not be visible in the installation in the exhibition.