In recent days I have posted on Facebook galleries of photos from recent exhibitions I’ve just seen, with a brief text which I typically write quickly, just enough to give readers a quick sense of the work. Since Facebook’s algorithm is notoriously unreliable, I thought I would republish two such brief reports, about works I saw in the past two days, especially since the works presented here propelled me into the studio, an effect of art work that I particularly noted when I began this blog. As is often the case, happenstance unexpectedly reveals thematics. This is a case in point.

Sunday December 21 * Here are some pictures of my visit to Night and Day, the Chris Ofili exhibition at the New Museum. I should say my first visit because I intend to go again, this is a show it is a pleasure to spend time with and the works make you spend time. I very much wanted to see the show although/because I haven’t seen that much of Ofili’s work, and my attitude was in a sense neutral because on the one hand I am not necessarily a fan of a kind of stylized style of figuration and yet I love cartoon figuration. Same duality about vivid color. So, needle set at neutral but looking forward to and anxious to see.

It’s a great show and by far the best use of the New Museum’s awkward cold space I have ever seen. Each floor tells a story and each room is not just a space to stick some work, but to consider a body of work. Important to go in order, second floor, third floor, fourth floor, and fifth floor for small exhibition of his work for ballet.

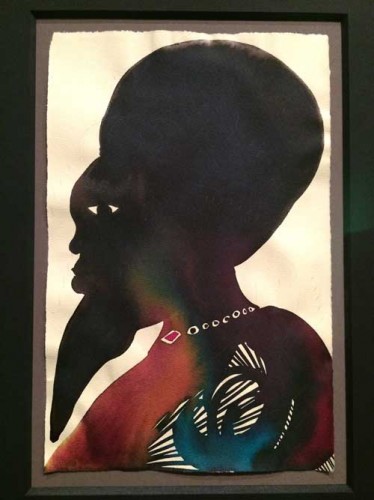

On the second floor, first thing you see coming out of the elevator is an installation of works from Ofili’s series Afromuses, 170 small framed watercolors (looks like watercolor and ink) of silhouetted heads of African women and men, emphasizing the abstract design of hairdos, patterned textiles of clothing and jewelry. These works, a selection of a larger series, emphasizes the importance of drawing–these were works that the artist did every morning for about 10 years for about fifteen minutes as warm ups for painting, and they serve here as a warm up to the rest of the show.

One experiences them twice, as you loop back to them after going around the corner first into a large space with a great group of large paintings from the 90s, including the notorious Holy Virgin Mary of Mayor Giuliani fame.

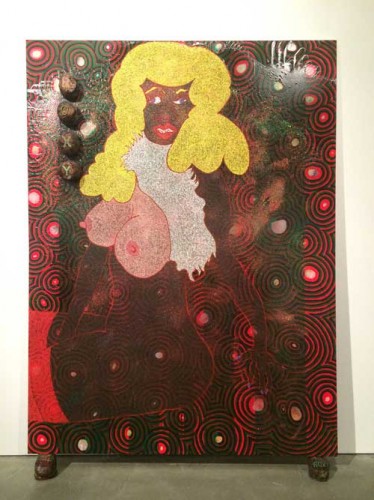

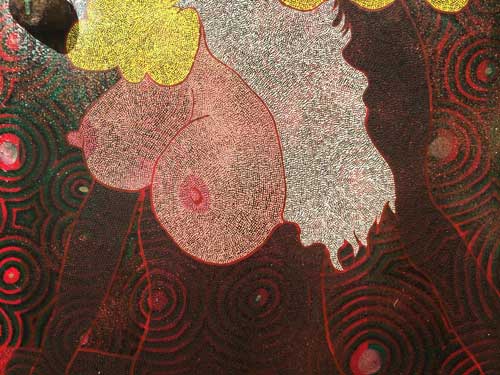

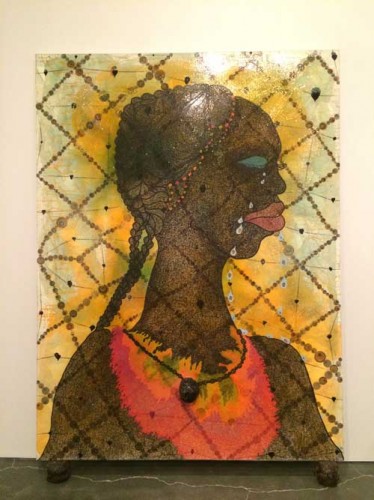

These paintings have a great sense of scale, and the fact that each rests on a ball of elephant dung adorned with the title of the work rather than being hung on a wall keeps them at the level of the viewer’s body. They are intensely surfaced, vividly pigmented, very funny–at one point I started thinking about the Simpsons–and very moving: particularly striking from across the room as well as directly in front of is No Woman, No Cry about the mother of a black teenager killed in a racially motivated assault in London. This painting’s use of the ball of dung is particularly striking, as a piece of jewelry which is also a weight, a scar, a tumor, at the core of the painting.

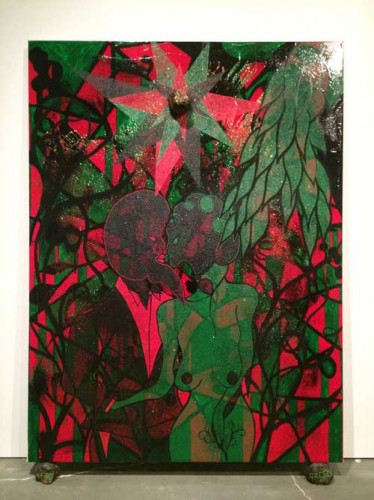

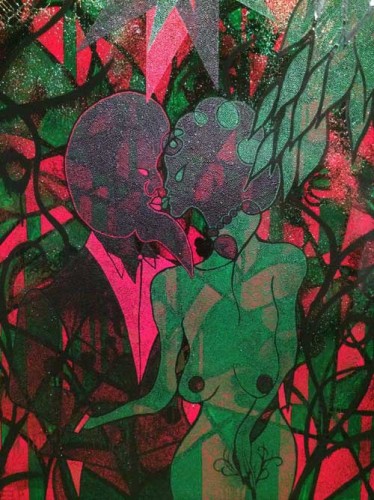

So already two impressive groups of works, but the show really gets impressive when one walks into the next room, lit slightly differently, with large paintings which share a color scheme of green, black, pink, red, and white, and a lush sexuality and sensuality.

At this point in the show looking at these works I also felt strongly that these paintings were made by the artist, that he was engaged in the painting, even though these are not conventional paintings–there is neither brushwork, ton smooth flatness, the surfaces are complex, textural, layered, constructed, but they are convincingly by one person making decisions as he goes along

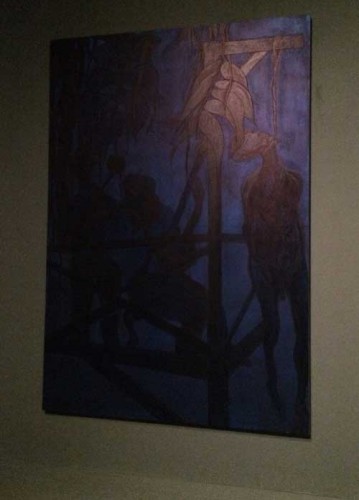

The next floor is dedicated to a darkened room with dark paintings which at first are nearly unreadable, somewhat like figurative Ad Reinhardts. Strangely my iPhone camera was able to pick out forms that my eye could not. The darkness hides dark subject matter including a lynching. It is a room I particularly want to return to, must return to, to see what more I can see.

The next floor (4th fl of the museum) is the total opposite, an emotional reversal: a knockout of color and sensuality, yet painted much more flatly than the first large paintings. No more stippling, no more varnish and glitter, no more elephant dung, in some cases figures appear to be drawn on the linen with charcoal. They bring to mind William Blake (an important artist to Ofili) and Nabis and early 20th century Viennese Orientalism, and also a lot of mid-twentieth century European artists, Matisse’s cut outs, late Picabia, Chagall even. The walls of the room are painted a light violet and blue floral pattern (based on images from Powell and Pressburger‘s movie Black Narcissus–a movie about Western sexuality repressed by religiosity and unmoored by its encounter with the exotic eroticism of the Himalayas–and painted on the wall by a team of professional scenic painters, according to the guard we spoke to). This helps transform the scale of the room in a way that is humanizing and welcoming, a large public space that one wants to spend time in, go back to, a vivid Botanical Gardens of painting.

The way I’ve described the show here is to give a sense of the experience floor by floor. There are some critical issues, or issues one could have a discussion about: how do these work somehow radiate a sincerity opposite from works from the New Expressionist period that share some of the same references to between the World Wars European stylization of the figure? Is the role and critical reception of stylized figuration, vivid pigmentation of painting, vivid patterning and gaudy surface different when the artist is a person of color with ties to Africa , now living in the Caribbean? How is the reception different if similar images are presented by a male artist or a female artist? The work itself resists these, often unspoken problematics, and this is part of their strength and affirmation.

Monday December 22 *

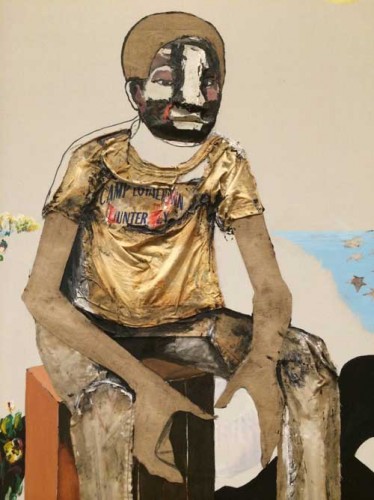

I went to MoMA yesterday and saw this really interesting painting by Benny Andrews: it is large, bold, arresting. Not a perfect painting–what appears to be a mutilated body covered by a crumpled American flag is awkward, not just disturbing, which it is, but awkwardly drawn, with strong foreshortening and the crumpled three dimensional cloth of the flag intruding into our space, and yet the painting, No More Games from 1970–is all the more powerful because of that awkwardness, a smoother painting would not be as effective, would be a contradiction. Each element means something, in the way that everything means something in a Northern Renaissance painting, there is iconography going on here, but iconography that is invented and adapted to speak to a desperate situation, a broken dream, the desperation of rebellion perhaps. Iconography is an important terms because in fact the painting also has a strong biblical reference, the painting is organized around a tree of knowledge and of patriotism that has been ravaged, leaving only the stump and the snake. Eve has been murdered for her sins–not sure about the sexual politics of this painting because its overall politics seem mainly about something other than sexual politics–and Adam sits with the body. Is it his crime?

The sun shines bleakly on bare canvas, it has burned the background away to a stark empty apocalyptic desert, and the figure of the man, “Adam” has a shade, a flat black shadow silhouette who springs from the same pair of high tops as the figure. This figure is very inventively painted and very sculptural, both representationally and literally, wearing a real T-shirt stuck on him like clothes on a paper doll.

No More Games. What a title for this moment, what a day to see it, when the senseless massacre of cops in NY arrives to devastate and demonize a budding civil rights movement.

A really strong painting, it would be nice if the museum saw fit to put some more lights on it, though the lower light on the right hand side and the fact that the painting is right off the escalator, in the hallway, means one comes upon it, the way you discover something powerful in the subway or on a street wall. By the way, the hallway seems to be the installation spot of choice for–often figurative (and perhaps not coincidentally often political)–paintings by “others,” Alice Neel, Robert Colescott near the bathroom a few months ago. No More Games is by far the painting that remains with me from all the paintings I’ve seen in the past few days, it is a political essay–a trying something out, as a painting it is trying something out in painting: Rauschenbergian–that is, post-War, use of the real on a flat modernist picture plane, within a Renaissance representational program, to speak to a political history that is rarely faced, especially within painting.

The painting is on the third floor, just outside a really good installation of late 60s/70s painting, sculpture, and video. The painting’s installation outside of the illuminating historical presentation is both insulting and fitting, given its subject matter, which cannot be properly contained within the institution.