Being 64 was very distant, for the Beatles as for me, back in 1967, but compared to my thirtieth birthday, today was a walk in the park. In fact I just took a walk in the Park to the Frick Museum, content to be alone on a lovely afternoon. I stood in front of the Pietà by a follower of Konrad Witz from 1440 and then in front of the nearly identical but flatter and more “primitive” but somehow equally powerful Pietà with Donor from the School of Provence, a near copy of the Witz school painting, from some time later in the fifteenth century, studied with the deepest engagement and pleasure the complex similarities and differences, why the less sophisticated painting nevertheless manages to represent Christ’s “humanation” (cf. Leo Steinberg) with if anything more contingent embodiment, while feeling sorry that anyone could today consider being an artist without giving themselves the opportunity to experience such works even if they are so far in our distant past.

Thinking back to past birthdays, turning thirty was a dark transition. Although my older sister Naomi told me that basically one’s twenties were an utter waste of time, as I turned 30 the energy, intellectual drive, and native optimism of youth that had gotten me past my father’s early death, through adolescence, into the world, into the artworld, suddenly dimmed. Old habits of being no longer functioned properly at my new age and in changing cultural conditions. I was blindsided by the radical changes in art, theory, and politics, which in 1979 became suddenly tangible if not immediately at least to me comprehensible. It took me several years to take the measure of the new culture and to adapt, essentially reeducate and recreate myself on my own, on the fly, not in school, more or less into the person who writes this blog, and my understanding of the meaning of those cultural changes continues to unfold even now, maybe more clearly than ever now, because we are only now, post 2001 and 2008, living in a present of the full effects of things that began to manifest themselves then.

I have had to recreate myself several times since then, as we all have to do. And, by the way, every major birthday since my thirtieth has been so much better, being whatever the age and also the actual celebration itself: by the time I arrived at my thirtieth birthday party, I had been so miserable about everything that some of the friends who were throwing it for me were barely speaking to me and the day was thunderous, humid, and sulpherously dark; I threw my fortieth for myself and it was fine; my 41st birthday, with chicken wings from Pluck-U and freshly blended strawberry daiquiris, was the most fun ever; 50 was fine though it was about 100 degrees and 50 was a great year. I threw a great party for my sixtieth, having gotten past the major regeneration of my life and work after the death of my mother. So I could take in stride a modest and quiet “When I’m 64.”

As one example of a reinvention: the year of 1983, as part of a desire to move from the kind of work I had been doing towards work that was larger, whose goal was to project a new and more accurate metaphor of self, one less fragile than that projected by my earlier materials of delicate rice paper, I turned from small works on paper to sculpture, done with plaster and paper on a simple armature, in a back-assed manner, since I had no technical experience in how to create something large by hand that would stand in three-dimensional space.

I worked on forms similar to figurative, nature-based stencil shapes I had developed in the early 80s, as in a delicate pastel and dry pigment work on rice paper from 1982, The Birth of the Little Shark, and my biggest most solid sculpture from 1983, the year of sculpture, was a work called Birthday.

Just one little fly in the ointment of “When I’m 64” is that some forces in the world turn their beady little eyes on you and want from you things that would require changing the few irreducible things you absolutely can’t change–the time and the place of your birth, the history you have inherited by birth, and the memory and lessons of the times you have lived through. In other words, you can learn a lot of things, and adapt as well as any of us can to changing circumstances and ideologies, but if you’re 64 the one thing you can never do is be thirty again. But, to those some forces in the world, as the song says, someday “You’ll be older too.”

But, staying on the positive, I thank my friends including my many Facebook friends for the many warm greetings and let’s sing along with Sir Paul, who is about to turn 72 June 18,

When I get older, losing my hair, many years from now

Will you still be sending me a valentine, birthday greetings, bottle of wine?

If I’d been out ’til quarter to three, would you lock the door?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me when I’m sixty-four?You’ll be older too

Ah, and if you say the word, I could stay with youI could be handy, mending a fuse when your lights have gone

You can knit a sweater by the fireside, Sunday mornings, go for a ride

Doing the garden, digging the weeds, who could ask for more?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me when I’m sixty-four?Every summer we can rent a cottage

In the Isle of Wight if it’s not too dear

We shall scrimp and save

Ah, grandchildren on your knee, Vera, Chuck and DaveSend me a postcard, drop me a line stating point of view

Indicate precisely what you mean to say, yours sincerely wasting away

Give me your answer, fill in a form, mine forever more

Will you still need me, will you still feed me when I’m sixty-four?

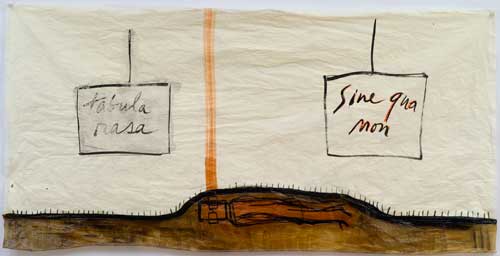

Tabula Rasa, Sine Qua Non, from 2013 (back on delicate paper): Sine Qua Non, what you carry with you, what the world says that you must carry with you, that without which you are not yourself, and Tabula Rasa, where you always begin again, seemingly at zero, with, and for a painter, on a blank slate.