Tomorrow August 16, the exhibition Abstract Marriage: Sculpture by Ilya Schor and Resia Schor opens at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. This exhibition brings to fruition a project I first thought of about five years ago. People have suggested to me that this will be a very emotional experience for me. Of necessity, in order to function, I have tried to discount this and see it simply as work to be done, but, as the works are installed, I am overwhelmed.

I wonder if people who look at art or who look at the artworld, and that includes young artists at the beginning of their life as an artist, know how much, practically speaking, it takes to get anything, however modest, done as or for an artist, how much psychic energy it takes to believe in artworks and to make others believe in them, particularly the degree of intensity of belief that at least one person must feel for artwork in order for it to survive after an artist’s death.

It is hard enough to maintain that belief in yourself as an artist and to act upon it in the face of the many rejections that most artists encounter, but to maintain that belief in artists who have died is even more difficult. You have to surmount the stasis their oeuvre and reputation fall into: as in a game of musical chairs or spin the bottle, the person’s reputation at their death is set at a mark, and then, unless the artist was already world famous and iconic and even if that is the case, the oeuvre is as much a burden as it may be a joy to the heirs and the reputation generally begins to recede from that mark achieved in lifetime. If the mark is slight, no matter the quality of the work, the person left with the responsibility of the work must go against the tide of history and of the market to maintain the work and bring the reputation back to the mark or forward to transform the recognition of the work. It is very hard to do. You become the custodian not just of the artist’s qualities and talents but also of that artist’s doubts and even the verities of their reputation. It’s hard enough for the artists to do in their life and harder to do for those who continue.

Several of my friends are artists whose parents were artists: like me they carry the double burden of belief, in their own work and in their parents’ work. Mimi Gross has done an incredible job developing The Renee and Chaim Gross Foundation, Susan Bee has curated exhibitions of the work of her father Sigmund Laufer and her mother Miriam Laufer. I spent several years editing The Extreme of the Middle: Writings of Jack Tworkov. Tworkov’s wife Wally and then his daughters Hermine Ford and Helen Tworkov had worked for over twenty years to have these writings edited and published. Jack died in 1982. Selections from his writings were included in the catalogue of Jack Tworkov: Paintings, 1928-1982, held in 1987 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. I began serious work on the texts in around 2003, The Extreme of the Middle was published by Yale University Press in June 2009. I did the work because I loved Jack and believed fiercely in his work and his writing.

My father died in 1961. My mother did everything she could to keep his work secure and his name in the world. She died in 2006. Included in Abstract Marriage are works by my father that were last exhibited in the retrospective of his work held at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1965 and that are unknown relative to other aspects of his work and works by my mother that have never been exhibited before.

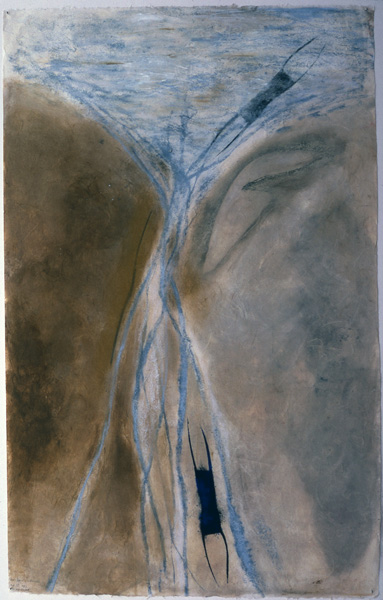

In the next few days I hope to write a post about my parents’ show, but today I mark Jack’s memory with a drawing I did on his birthday, August 15, in the summer of 1982, as he lay dying at his home in Provincetown. The drawing is called For Jack’s Leaving. Jack loved the bay of Provincetown, the sand flats, the daily swim. In the drawing, I depicted that moment when the outgoing tide pulls water out of the bay through shallow channels, rivers two or three inches deep running out through the sand flats. The figure goes through a narrow channel towards the open sea, like a reverse of birth.

In his diaries, Jack wrote on his birthday August 15, 1953

August 15, 1953

Technically my birthday. The idea had crossed my mind today that I am in every way a self-made man. Even my name and my birthday are self-made. To be fair, I simply mean that my birthday was only a rough approximation like my name.

Typically scrupulous, he later corrected himself, he had written that entry into his journal a couple of days early. But then, on August 22, 1953, he reflected on the great cultural leap he and his sister Janice Biala made after they were brought to America as children.

Janice and I are the first in our line. Our parents are as distinct from us, as the American Indians. It is impossible to convey to a western mind what my mother is. The distance between her and me can only be counted in centuries. But not only time stands between us but differences in adaptation as vital as that between sea and land animals. In fact I think of Janice and me as having become land animals in one jump. As if our parents had been utterly sea animals. Yet we are only land animals of one generation with all the weaknesses that implies. I was brought up to regard timidity as if it were the first rule of life. And the cancer of indolence was planted in me in the cheder. I was brought up the first ten years of my life for another environment. My mother is to this day sealed in that environment, and she has no crack, no window, to look out upon the world. My own distinct situation, the inner break from my mother, did not become apparent to me till so late in life. Did I become aware too late? If I were willing to take all the risks could my life still become vigorous? Or is that question itself a sign of my still unsolved problem? Should a man dream to change the caste of his life when he is past fifty. Does maturity mean to live with one self whatever the self is?

The summer my father died, the Tworkovs invited my mother and me to spend a month with them in their house in Provincetown. Jack wrote in his journal of my father’s death but also of how the work of the artist lives on after his death:

August 8, 1961, P’town.

No place in this notebook have I so far noticed the death of my beloved friend Ilya. His image hovers in my mind. His lovely gayety, the sparkle, the aliveness of his eyes, the humor that played on his lips like honeybees on flowers. Now Resia is here and Mira. We sat long over our coffee this morning talking about people and gradually we drifted into talking about Ilya, each of us displaying our love for him as if he were alive and with us. Even through her unbearable grief her face suffuses with light when I praise Ilya. […] She said something remarkable recalling Ilya. She said, the test of a work is does it speak for the artist after he’s gone. In life the artist persuaded us by his personality, but after he’s gone only his work is left to persuade us.