This is the first of a number of projected posts I hope to weave into A Year of Positive Thinking, on the theme of “Teaching Contradiction.”

Poised as those of us who teach or are students are between the last episode of the reality show “Work of Art: The Next Great Artist” on Bravo Network and the beginning of the academic year, this seems like a good time to examine how some of the contradictions enacted in the final episode of that show replicate contradictions that exist within the expectations placed on artists studying in MFA programs around the country.

The final show of what is currently being described as the “first season” of “Work of Art” established a contradiction in its own narrative premise: each episode but the last was structured around a “challenge.” The artists were given an assignment and either alone or in collaboration drawn by lot had to produce a work in about 24 hours with sometimes deliberately limited materials (you know something is wrong when A. you get only $100 to spend at Utrecht, whereas many decent old fashioned art supplies such as a tube of good quality of cadmium red oil paint can cost $50 and B. a lot of artists don’t use the kind of materials carried at Utrecht).

This seemed to be an entirely unrealistic depiction of creative work, since that brief time had to include coming up with an idea, shopping for supplies, dealing with all kinds of production demands, and doing the piece. This pace is more suitable to Bravo’s Top Chef series, since every day in a restaurant kitchen is a nearly 24 hour cycle of shopping for fresh produce and preparing dishes on demand under theatrical conditions of intense pressure with due speed whereas the time frame of the “Work of Art” challenges precluded both the kind of contemplation (reflection, research etc) or craft (here understood as refinement or finish) that are generally considered an essential part of artmaking (and since $100,000 –one the biggest individual artist grants in the world– was at stake you’d think that would matter but I digress…only slightly). The artists who did best had some basic skills –traditional craft skills such as carpentry and mold-making seemed particularly useful–and were quick to come up with a concept, though often these were extremely literal and illustrative, a problem shared with much contemporary art.

However, to the contrary, in the last episode of “Work of Art,” the three finalists were given 3 months and $5000 to produce a body of their “own” work for a show (the fact that anyone would get $100,000 for mostly not doing their “own” work is …again, I digress). For the most part this allowed them to produce more polished work in terms of materials and surface finish though their conceptual apparatus seemed remarkably unchanged by the relatively more expanded time. Strangely the person most gifted in the short time-frame, Miles Mendenhall, who under pressure was quick, slick, and clever, knew how to make things, and how to occupy space convincingly, did not fare as well with more time, losing spatial energy while revealing the weaknesses in his conceptual frame.

Much discussion on Facebook, Jerry Saltz’s much awaited weekly recaps, and various blogs pondered how much this particular reality show with its for the most part silly assignments, awful art, weird costuming, and lack of articulated critical and aesthetic discourse or criteria even when compared to Project Runway and Top Chef had to do with the “real” artworld. Sorry Jerry, but, perhaps because of editing, the uninformed viewer would get little background on the various contexts and references that make up the aesthetic criteria used by the judges.

In this contradiction between premise #1, pressure to produce art work in a short time within a group situation and premise #2, longer time frame for private production, “Work of Art” did bear some resemblance to one of the basic contradictions operative in two-year MFA Programs: in the equivalently short amount of time given to get an MFA degree, students experience an overwhelming exposure to a bewilderingly vast amount of diverse new artists, ideas, theoretical languages, art styles, aesthetic and political criteria (many of these contradictory), they are given lots of theoretical texts to read and are expected to see exhibitions and go to every art event they are told about, and yet they are expected to produce work regularly for critiques and discussion with teachers and visiting artists, (while, to name another contradiction, often limited to tiny studios with little privacy while implicitly expected to compete with works in museums and galleries produced with enormous yet mysteriously obscured budgets).

As a teacher, I enact the demands of this contradictory situation yet at the same time I am particularly sympathetic to its stresses because in the last 10 years a curious split in my work practice which has its roots in my earliest years as an artist has become acute: my deepest, most meaningful and most productive immersion in studio practice takes place during barely two months of the summer and away from New York City, and the much longer months of the academic year are spent in New York working on jobs (including teaching), working on my work (which may involve working with my works in digital reproduction, archiving + all the editorial, secretarial and social work that goes into even a modest career), and immersing myself in the multiple influences of current thought and art. All that uses up a lot of “bioRAM” as a friend of mine terms it, which in the summer goes entirely to the immersion in studio work and thought. Writing is the only activity that is continuous because it is an extension of thought and is stimulated equally by discourse and debate within the artworld and by time alone inside my mind.

The city mouse/country mouse dichotomy extends to my teaching itself: just as I paint and write, just as I imbricate written language into the language of paint, I approach the development of the artist in the classroom through text and history and in the studio through a variety of more formal and also more intuitive approaches and vice-versa: I’m committed to the artist as a historically produced thus educated to history, culturally contextualized person who should have as much control of theory as possible so it won’t have control of her–but at the same time I love the development of working–call it studio practice even when it isn’t what that used to mean or what I do–and I know that creative work needs to occasionally be unmoored from overdetermination.

In this city/graduate school environment, the upside of constant interaction/confrontation with people, work, and ideas that you have to understand, absorb, react to, sometimes defend yourself against, yet often allow to transform you, is that complacency is hard to come by. The downside is that there may not be time to process everything and all the outside voices can drown out the interior ones or, even, according to certain theoretical outlooks, deny that an inner voice exists inasmuch as it might be associated with autonomous art practices which have been deemed obsolete. And you are constantly having to put yourself forward, which for the MFA student means constantly talking about what your work means leaving little time for either doing it or for doing work whose meaning you might not have a ready explanation for, work that is transitional, even work that is a “failure.” You become all outside speech and less inside voice until you are running on empty.

Mira Schor, Voice and Speech, 2010, ink, gesso, and rabbit skin glue on linen, summer studio snapshot

Since I have always reaped tremendous energy for my work and my writing from work that at first and sometimes finally at last, seems antithetical to my own, these encounters produce my work, they are an important part of it. Dealing with the “real” world of “winter” battles is absolutely necessary. Yet so is the uninterrupted and intimate availability to my work that I feel I need in order to really paint. It’s always hard to come by, hard won, and even hard to recognize as it is happening. It relies not just on aloneness but even on loneliness. It can come out of a desperation that makes you take chances –like the Diver on the postcard at the top of my studio wall array of postcards or like the demon of fear of failure that Agnes Martin discusses in her visionary essay about creativity, “On The Perfection Underlying Life.”

In recent years debates have intensified over the the possibility of alternatives to institutionalized graduate school, as degrees proliferate and tuition costs rise disproportionately to the earning power of most artists. Thinking of this split between information and critical discourse on the one hand, and studio/post-studio/post-post-studio practice on the other in relation to the usefulness of graduate school, one could truthfully state that the knowledge one is exposed to in school is available in the world at all times, especially in urban centers: museums, galleries, books, art magazines, internet sources, panel discussions, artists’ lectures all abound, though graduate school intensifies, categorizes, and filters that knowledge through the interpretive structuring lens of the school’s ideology and its faculty’s strongly held viewpoints while insisting on disciplined and timely engagement and response on the part of the student. But critical responses to your artwork by individual artists and critics is much harder to come by outside the academic structure, people are just too busy and will certainly not be able to give sustained attention, so if you don’t do the work when you’re in school, you lose out on the unique opportunity to get concentrated and sustained feedback, when you want it and even when you don’t.

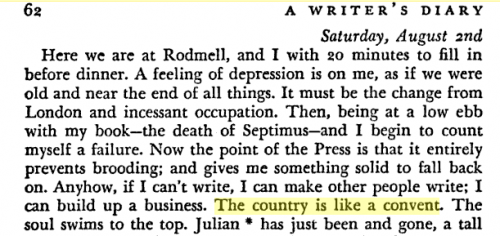

In a couple of diary entries from 1924, Virginia Woolf discussed the duality of work environments in her life –London/discourse/data input/sociality, and the country/solitude/introspection: “the country is like a convent, the soul swims to the top,” (August 2nd, 1924). I read this sentence when I was in my twenties and just beginning my city/country split work life and the sentence stayed with me. I found it just now through a Google search in 30 seconds, since evidently she is the only person who ever expressed that thought in those words:

Virginia Woolf, from A Writer's Diary, August 2nd, 1924, page 62

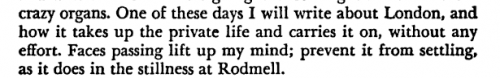

Yet the isolation and solitary confrontation with her work also brought on depression which the bustle of London dispelled. May 26th, 1924 she had written:

…

No matter whether it’s a reality TV show, graduate school, or the everyday life of the working artist, it is always a matter of constant negotiation between world and self, the art itself and the making of it.

Note in the sand, 2010