Uptown, at the Met, April 22

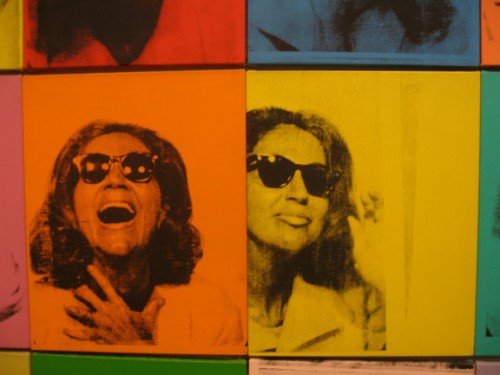

I arrived at the Met late in the afternoon, having stopped first at Acquavella Gallery to see Robert & Ethel Scull: Portrait of a Collection. I feel like I knew the Sculls personally because I show Emile de Antonio’s 1973 great documentary film Painters Painting whenever I teach about the New York School, which means often. The Scull’s appearance is a highlight of a film full of highlights: I love the scene where Ethel, with a vivacious enthusiasm that seems at once genuinely innocent and rapaciously disingenuous, describes Andy Warhol, armed with bags of coins, creating her portrait by taking her to Times Square to have her picture taken in photobooths in a tacky arcade. So it is great to see the painting in the show:

Andy Warhol, detail, "Ethel Scull 36 Times," 1963, acrylic and silkscreen on canvas, 100"x144"

I also feel like I know the Sculls because of Jack Tworkov’s description of them in a diary entry + note scribbled on the back of an American Airlines ticket envelope, returning from a trip to Buffalo for the opening of a new wing at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery:

Friday, January 19, 1962

Took plane with Leo for Buffalo. Sat with Sculls. New People, like cheap bright aluminum pots. For whom is “Avant-Garde” art intended, for them obviously. They never say art without the prefix Avant-Garde.

*Vulgar people—I don’t mean not nice people. They can even be pleasant—nevertheless they can be embarrassing. They are unsure still of their accent, their reading matter, their pleasures, their vacation places. They use all these things for self-improvement which is itself vulgar and I speak as one who has suffered all the self-improvement I can stand. They [are] embarrassed with their own status, eager to acquire through culture what has been denied to them because of family background, race, religion or the unaccustomed uses of recently acquired wealth. Since they are fundamentally embarrassed people they are essentially unaware and make little use of their fundamental strength—what is peculiarly their own (as the elite knows so well how to do) and make a great show of borrowing clothing of what is after all mere social disguises. These people are really new people as new as an aluminum pot. It is for them essentially that avant-art is made. They are the mass market for what chic initiates.

All the more amusing then that the show is installed in such elegant upper East side mansion style rooms with ornate moldings, parquet floors, French windows, and gilt-framed mirrors. Nouveau Riche meets Edith Wharton New York. Two excellent early Rosenquist paintings were a nice surprise, both very restrained in color, both working from the photographic but not yet based on commodity or military spectacle: the flat color and use of disappearance and deletion within the appropriated photographic image in Untitled (Blue Sky), 1962, reminded me of much more recent works by John Baldessari . Another surprise: Jasper Johns did paint some bad paintings back in the day! Johns’ Double Flag from 1962 is in my opinion a rare stinker from that period, I’m not sure whether this is because of the particularly pedestrian use of realistic color in this work or the rather slack paint surface quality (the gallery web site perhaps wisely does not include an image of this work).

James Rosenquist, "Untitled (Blue Sky)," oil on canvas, 84"x72," 1962

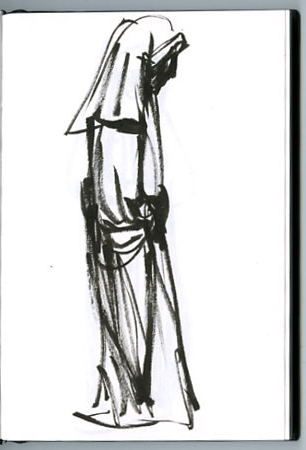

At the Met, with only forty-five minutes before closing time, I decided to just look at the The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry. An amazing show which required more time than I could give it since each miniature painting necessitates careful examination with one of the magnifying glasses supplied by the museum in order to fully experience its monumentality, but the surprise for me were a group of astounding and curious sculptures I encountered unexpectedly in passing as I was speeding back through the Medieval Sculpture Hall towards The Art of Illumination, which is in the Lehman Wing: in the center of the hall, on a simple platform, stands an eerie procession of thirty-six small alabaster figurines, lined up two by two, led by two even smaller figures. These are The Mourners, Tomb Sculptures carved by Jean de La Huerta and Antoine Le Moiturier between 1443 and 1456 to adorn the tomb of Duke John the Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria. They’re usually set into Gothic architectural niches so this exhibition offers an unusual opportunity to see them in the round.

I have a weakness for representations of drapery in painting and sculpture. Here the style of representation is realistic though with a trace of Gothic elegance, caught in time between the massive sculptural rendering of drapery on many figures in the work of Giotto of the early fourteenth century and that of Zurbaran’s more naturalistic and yet also more dramatic depiction of similarly garbed and hooded monks, from the early to mid-1600s. These figures were once polychrome: this and much more historical context for these figures can be found in a recent book review by Anthony Grafton of The Mourners and the catalogue of The Art of Illumination.

Mourner with drawn hood, alabaster, 16 1/2"x 6 1/8" x 5 1/8," Jean de la Huerta and Antoine Le Moiturier, 1443-1456

There is a weird resemblance to Obi-Wan Kenobi in the exquisitely rendered drapery of the monks’ robes with cowls often completely obscuring their faces (though if one peers into the shadow of the cowl, their features are as delicately carved as the most expensive nineteeth-century porcelain doll): of course the train of influence runs in the other direction but you can’t help but think of Star Wars for a minute, until you experience the specific features and accoutrements of each mourner. Because of the dominance of drapery these sculptures are as abstract as they are figurative, and as monumental as they are doll-like. They are really fascinating little figures, mourners but poker-faced. Despite the drama of their depicted grief, they have a precise kind of calm in their form.

Mourner, Jean de la Huerta and Antoine Le Moiturier, 1443-1456

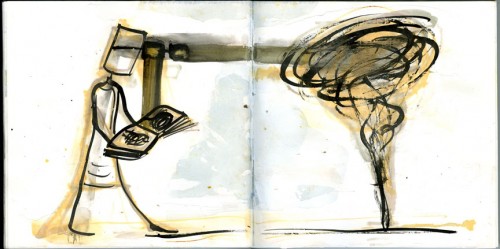

Mira Schor, sketch of what I think is the figure above, seen from the side

I was particularly interested in the figures holding open books, since this is an image I have recently been working with, a figure — myself — who, among other things, is a mourner reading the book of the past while walking into the future. Despite the fact that I am in fact drawing such figures in my work, I was irritated that photography was not permitted at the Met (and annoyed at the vigor which the guard applied to her enforcement of this rule) so that I had to make do with some quick sketches, which proved particularly ineffective: usually my sketches of artworks recall the work in a more vivid and embodied way for me than any pictures I take at the same time, but even when looking at the special website for this exhibition, which allows you to rotate the figures 360 degrees and look at them from three vantage points (from above, eye level, and from below), I still can’t be sure I recognize one of the figures I drew, attracted by the Gothic elegance of a slightly slouching slim pose.

I feel there is something very useful to me about these sculptures, individually and their grouping, here particularly the idea of the isolation and privacy of individual mourning in relation to the rituals of collective mourning. Because they’re resonant of some aspects of work I am doing, they suggest something about what I might do, as yet unknown to me .

Mourner with drawn hood, reading a book, Jean de la Huerta and Antoine Le Moiturier, 1443-1456

Mira Schor, 38th spread, Grey Summer Notebook, ink and gesso on paper, 9 7/8”x14”, 2009