The first time after September 11 that my friends and I met in Chelsea to see some exhibitions which had had the misfortune of having their opening scheduled for that day, we were ecstatic to see each other and to be out in our city. We were, however, repelled by much of the art that we saw. It had all been done before. It looked empty and now we needed not art world stuff, fluff, what my mother used to refer to contemptuously as “merchandise,” but substance, art that showed some awareness of the world we were now living in, one totally altered from the one we had thought we occupied September 10.

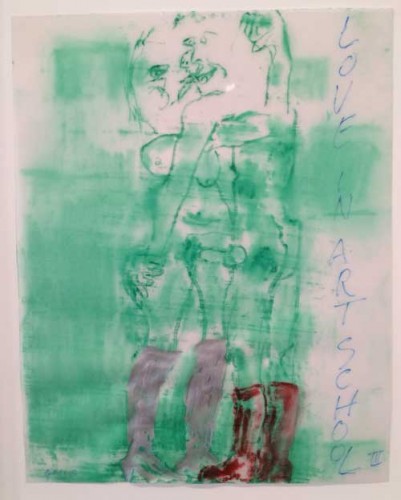

Now as I write we are on the eve of a calamity perhaps greater. But for some reason, in some cases with forethought or based on some quick planning, there have been some powerful artworks on view in New York during this election season, artworks that really address the political moment while providing models of how one can do it, that most difficult thing, make an artwork, particularly a two dimensional static one, drawing or painting, that has an acute political narrative and a powerful aesthetic presence. Notable among such shows have been Philip Guston’s “Laughter in the Dark, Drawings from 1971 & 1975”, including his “Poor Richard” and Phlebitis Series, Kerry James Marshal: Mastry at the Met Breuer, and Benny Andrews’ The Bicentennial Series at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

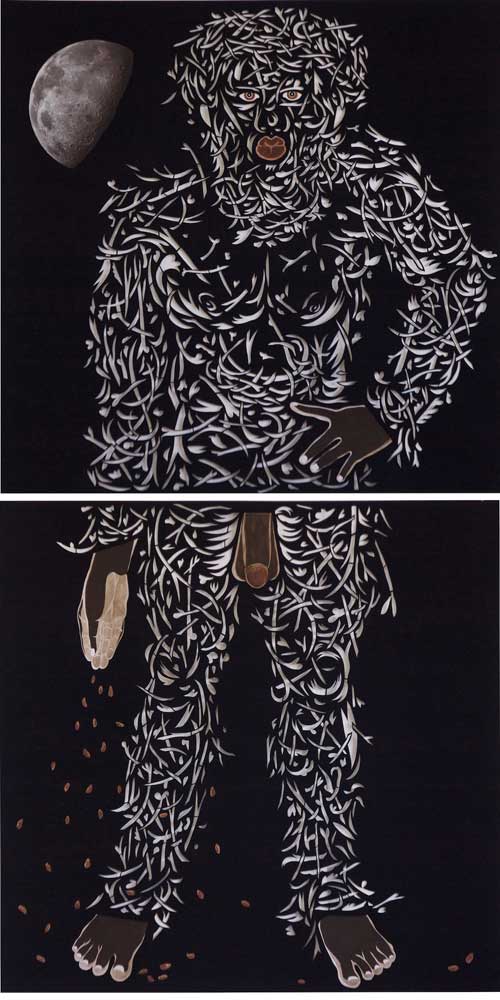

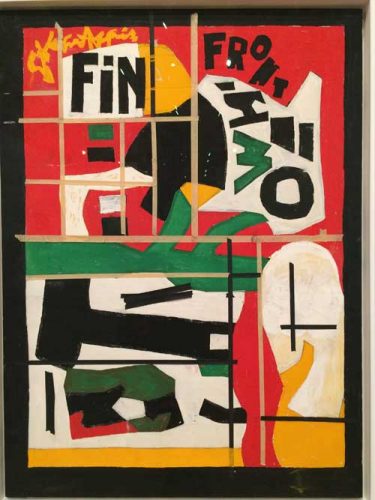

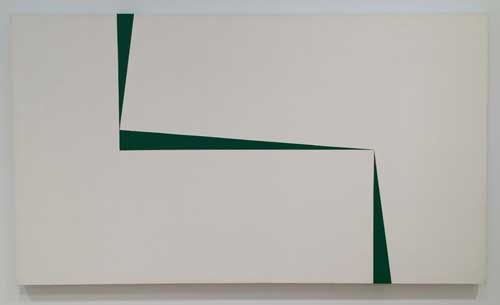

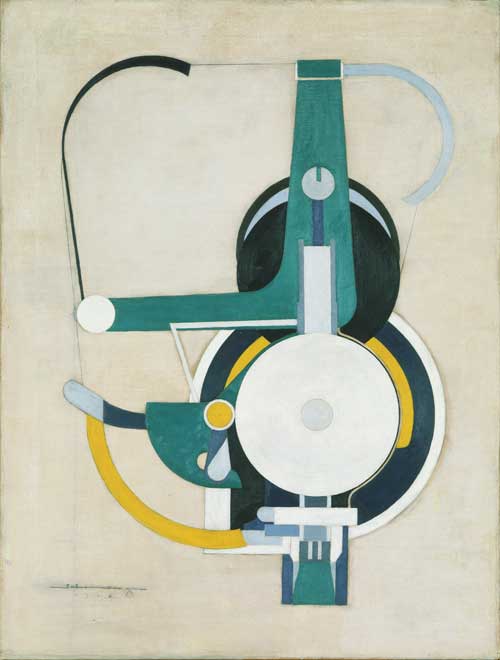

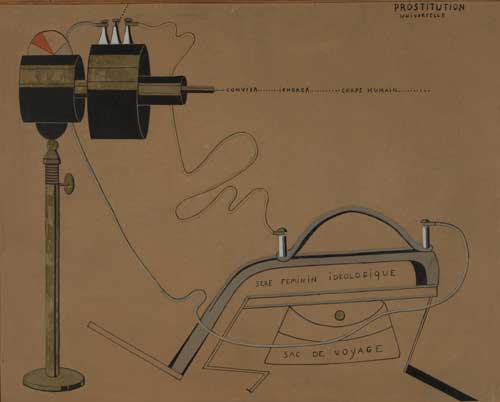

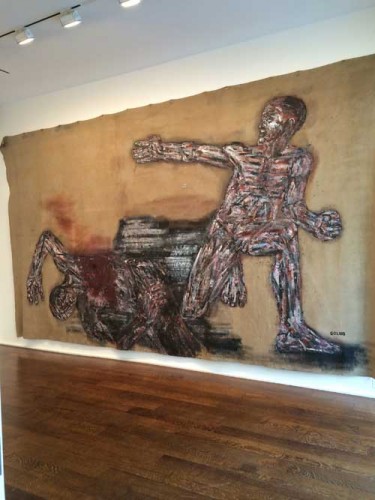

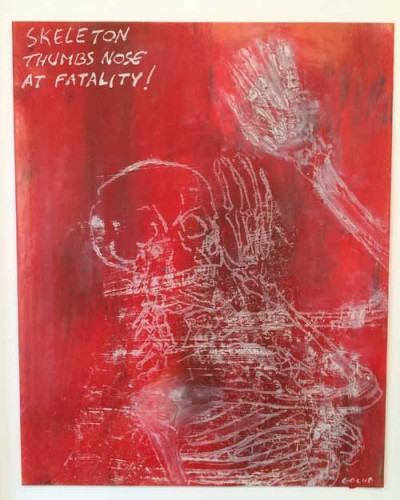

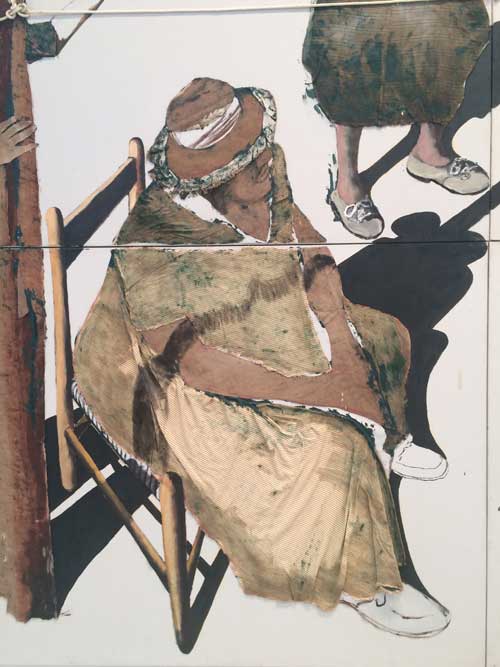

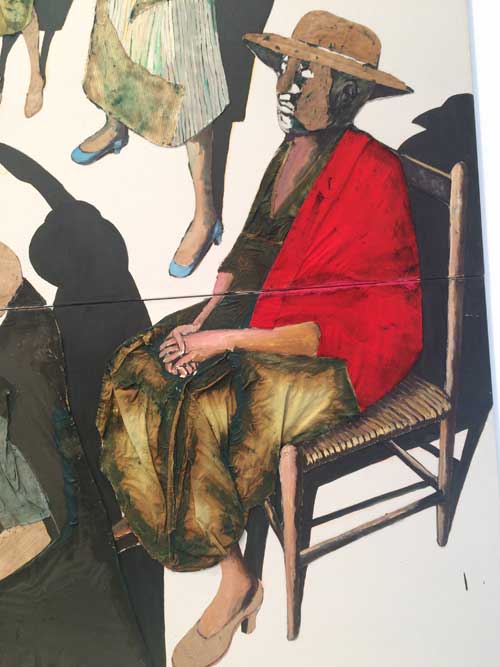

Benny Andrews (1930-2006), “Circle,” 1973. Oil on twelve linen canvases with painted fabric and mixed media collage, 120″ x 288″. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

I have wanted to write about one of these major paintings in Benny Andrews’ show, Circle, from 1972, since I first saw it earlier this fall. When I first saw it in November, even from far, from the narrow hall, I thought, oh, here is a masterpiece, a word I rarely use. I wanted to proclaim in writing, “there is a masterpiece on view in New York.” Circumstances intervened and now the painting is on view for just a couple more days, extended through Saturday January 21.

Circle (1973) is one of a cycle of very large multiple canvas works Andrews completed the early 70s dealing with both racism and sexism done at an intersectional moment in American history when the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement and the Women’s Liberation movement reached a peak of visibility and even transformational effectiveness, as the nation approached its Bicentennial. In 1969 Andrews, a New York based artist reared in rural Georgia, Korean War veteran, activist in the Civil Rights, anti-Vietnam War, and feminist movement, undertook a major cycle of works, creating one major work per year for six years building up to the Bicentennial in 1976, each work emerging from dozens of smaller paintings and drawing studies.

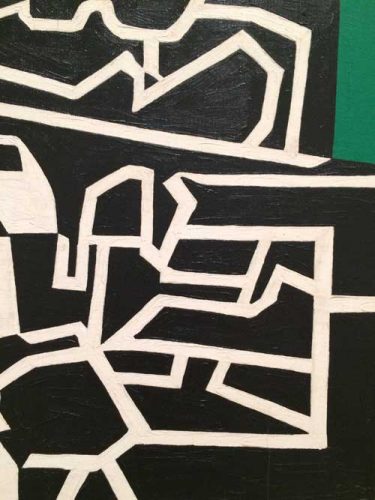

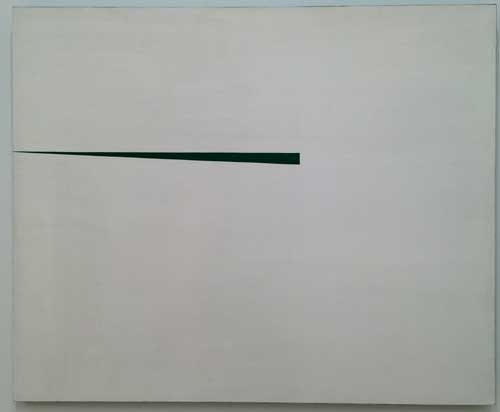

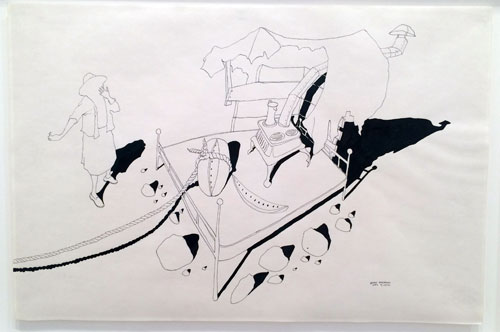

Benny Andrews (1930-2006). “Circle” Study #32, 1972. India ink on paper 12″ x 18″, signed and dated. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Andrew’s project sprang from his concern that the African-American experience would not be included or addressed on its own terms, in its own voice, in the nation’s celebrations. Each work including Circle began with a few ideas, images, and memories, which Andrews worked through in dozens of drawings and smaller painting studies–a fact I note because often in recent years I encounter art students who think you can just do one thing, try an idea once, not realizing the kind of work that goes into working through ideas until you arrive at the most powerful form and thus also the most powerful metaphor.

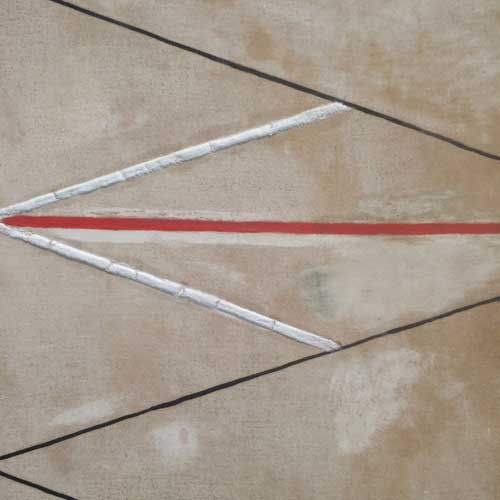

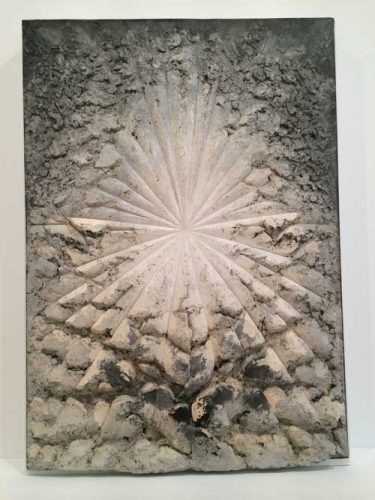

Here was my first impression of the painting: Circle is a painting with collage elements of cloth, paper, and rope, on 12 linen canvases assembled to create one very large surface. At the center of the work a black man is crucified to a bed by real rope strung across the canvas. He is bound, naked except for underpants made of real stained rags, and his body is slit open with his bloody innards a split watermelon. The bed itself is a humble plain palette covered with blood stained mattress ticking. The crucified figure is held down by a circle of white women who hold the ropes tight, some scream, some are faceless, behind them their shadows are foreshortened into black silhouettes. The scene is framed by two older black women seated in rush chairs, impassively witnessing the lynching….Here is my second impression of the painting: A black man naked except for soiled underpants is tied to a bed at the center a large rectangular space, his body is slit open to reveal the inside of split watermelon, while a complex contraption above him is pulling three-dimensional watermelon like forms out of his gut. He is held down by real ropes held by a circle of mostly women and some men, encircled the figure, some very close to us the viewers, some farther back and above us in the picture plane. Each figure including the circle of torturers, the man, and even his bed cast black shadows, created by a light source that seems to come from our space in the gallery into the painting, implicating us in the circle. All the shadows fall away from us toward the background, except for the man’s right hand which casts a claw like shadow in the reverse direction, reaching in effect towards us, the viewers.

When I first saw the work I interpreted some of what I saw in a manner that seemed narratively inconsistent: I read the two seated women in the foreground as black though that didn’t make sense, for what would two black women be doing seated impassively at a lynching? Yet it made some kind of sense to me, or I created sense: I saw them as tribal elders, archetypal matriarchs who had seen everything. One can build any interpretative narrative out of visual clues. Today the visual clues were the opposite: I felt that the circle of torturers including the two seated women all had to be white. I’m still not sure. In the gallery text on the exhibition, in the discussion on this particular work, it is noted that the images in this painting were interpreted in multiple ways, and that “in conversations with critics, Andrews stayed silent on the personal intent behind his symbolism.” Between common sense and instinct there is a range of possible interpretation. Either way these drawn, painted, and collaged, built up, seated female figures are powerful and eerie witnesses to a deeply disturbing event.

My description of the narrative does not really explain why I call this a masterpiece. Let me try to get at the core of it: the work is large and thus impressive because of that, but that would not be enough, there are lots of empty-headed large paintings around. So it is large and it depicts a powerful and disturbing event, it is in a line of history back to paintings depicting the martyrdom of Christian saints, the flaying of Peter, and of course scenes of the Stations of the Cross, the Crucifixion, Deposition, and Lamentation. But it takes place on a flat white ground, someplace that is very modernist in its flatness, and this place is a nowhere, bleached out of detail: only one exotic tree hints also at a biblical theme as a white woman hands some fruit to a white man who is clinging to the trunk of the tree. And it is not exactly a painting, as each figure and object that appears is composed from two dimensional and three dimensional elements. It is as sculptural as it is painterly.

The use of actual rope which we feel palpably as we look at the work–we see its texture and the shadows the rope casts on the surface–this binds up to the paintings as much as it binds the figure to his bed of suffering. Its reality enters our space and it implicates us. The ropes do something else as well, they bind the painting, and they cross the lines created by the individual canvases that create the surface. The use of these 12 canvases to create one large work was in part the result of circumstance, the size of the artist’s studio could not accommodate one large work:

The idea of my new work is the expression of an individual, in this case, a black individual, in America, in the 70’s, using the Bicentennial as focal point. throughout the work, I emphasize the history of this country over two hundred years. My new work forces me to position myself in that kind of arena. Though I don’t work on the idea of the spectacular, I did want to work on the challenge of bigness. I had to do the “big”work even though I had to do them small enough in sections, so they could get out of my door and down the staircase of the building. So as I worked in my studio, I said I have to approach this honestly, and I made no attempt to hide or redesign the panels or the lines between them.

But that decision is part of what makes this such a brilliant addition to the grand tradition of painting: the lines of separation between the canvases undermine that tradition even as they build upon it and speak as an equal to it.

I think of this as a great American painting, because it depicts American history and emerges from the artist’s lived experience of Jim Crow in the South and institutional racism in the North. It should be as celebrated as Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, or James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, or any song by Mahalia Jackson. But I think of it also in relation to the great tradition of Western painting, culminating as it once did in an installation in the Louvre of Courbet’s A Burial at Ornans and The Painter’s Studio, Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus and Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa. It should have pride of place in a major American museum.

Now as ever there’s a lot of talk about the effectiveness of art in or as political activism, particular the old art of painting, which is seen as static, and also as compromised by its association with the history of both Christian and secular capitalist Western power. And it’s very rare that a work of “political” art has made a difference in a specific political situation. In fact often such a work is not even widely seen at the time. Edouard Manet prudently didn’t exhibit his work, The Execution of Maximilian for several years because it would not have been safe to do, similarly James Ensor rolled up Christ’s Entry Into Brussels in 1889 and it wasn’t exhibited for thirty years and for all I know stowed it under his bed. Picasso’s Guernica is one of the rare works done in reaction to a current event that was known at the time it was done because of the fame of the artist.

And of course none of these works whether seen or not would have altered the course of history. Nevertheless when these works are seen at a later time, they hold within their visual and material decisions the power of the artist’s connection to the subject, which is power/powerlessness and injustice/justice. The works have a political effect: they give people courage, when they are seen, whether it is during the artist’s lifetime or a hundred years later. And speaking selfishly as an artist: the area where I feel the courage is not only the area of political activism, but as an artist That is, it is not only the subject, but the form, or it is the conjunction of the two, but if it were only the subject, it would most likely not have the effect of giving me courage, as an artist.