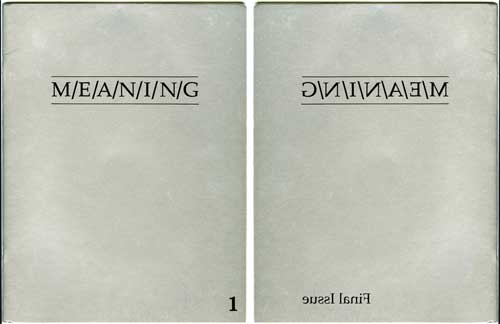

The first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A Journal of Contemporary Art Issues, was published in December 1986. M/E/A/N/I/N/G is a collaboration between two artists, Susan Bee and Mira Schor, both painters with expanded interests in writing and politics, and an extended community of artists, art critics, historians, theorists, and poets, whom we sought to engage in discourse and to give a voice to.

For our 30th anniversary and final issue, we asked some long-time contributors and some new friends to create images and write about where they place meaning today. As ever, we have encouraged artists and writers to feel free to speak to the concerns that have the most meaning to them right now.

We began on December 5 and every other day since we have posted a grouping of contributions on A Year of Positive Thinking. We thank our contributors and readers for living through this time with all of us in a spirit of impromptu improvisation and passionate care for our futures.

This is the last post of the final issue.

Susan Bee and Mira Schor

***

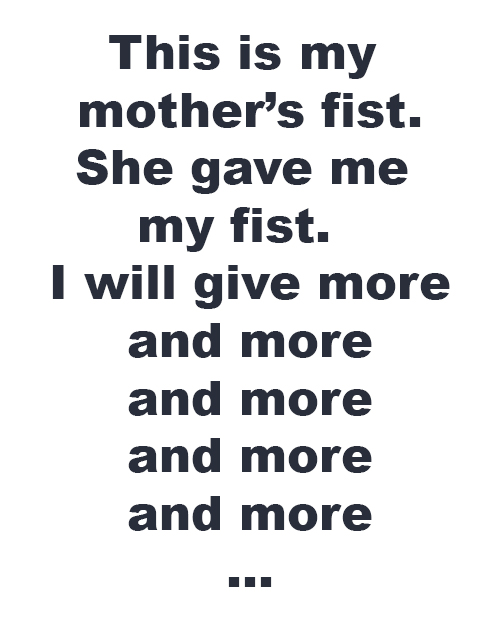

Susan Bee

This final issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G brings back memories of our first issue, which came out in December 1986. At that time, I was a young artist and a new mother, working at freelance jobs as an editor and graphic designer. I had a baby at home and was full of optimism. Emma was born in May of 1985 and tragically she died 23 years later in 2008. I was 33 when she was born and Mira and I started to think of starting our own arts publication.

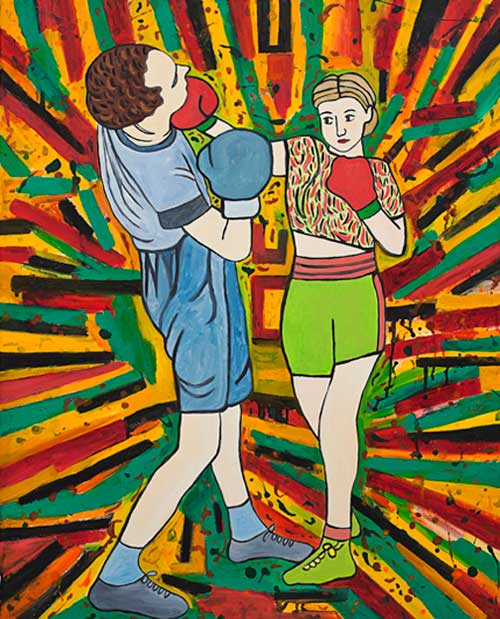

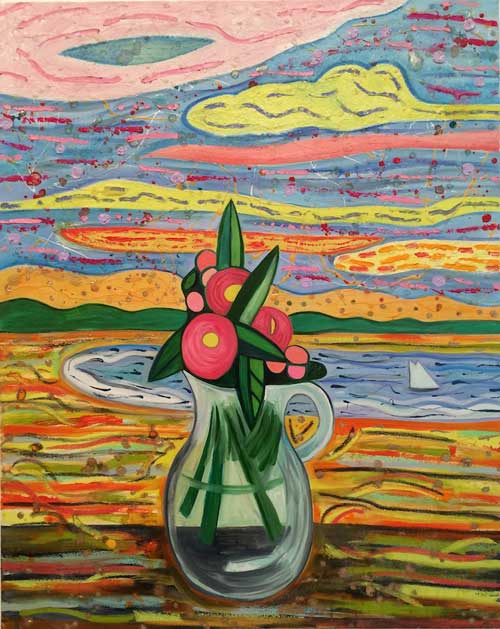

Susan Bee, “Non Finito,” 2016. Oil on linen, 24″ x 30″.

In 1992, I had my first solo painting show, when I was 40-years-old. Now, I’m almost 65 and nearing the traditional retirement age with a 24-year-old son, Felix, and a 40-year marriage to the poet Charles Bernstein. I have been a member of the vibrant all-women artist’s collective, A.I.R. Gallery, for 20 years and will have a solo show of new paintings there in March 2017. I have been teaching, publishing artist’s books, and showing my art for many years.

This election has sent me into a tailspin. I hoped to be greeting a woman president in my lifetime, and now the possibility seems remote and I am heartbroken to be facing the next four years of this administration. As a secular Jewish feminist, artist, and professor, the future in this country that my immigrant artist parents, refugees from Berlin and Palestine, came to in 1947, looks bleaker than it did just a short time ago on Election Day. Since that day, I have been taking refuge in viewing art. Through the contemplation of art and poetry, I have been trying to escape the isolation and desolation of the present moment. I know that we need to fight on and that I need to work with my community to create a strong push back to the hatred and bigotry that surrounds us. My optimism is being sorely tested by the hatred that has been empowered in this country.

Susan Bee, “Afraid to Talk,” 2016. Oil, enamel, and sand on linen, 24″ x 30″.

Now, my 30-year editorial partnership with Mira is coming to an end. However, I have no plans to retire from art and life. I am grateful that we had the opportunity to publish over a hundred critics, poets, and artists. Hopefully, the artists, writers, and other creative spirits, who have nourished our project, M/E/A/N/I/N/G, for all these years, will continue to lead the way forward and point us to a future that will enrich us all.

November 2016

Susan Bee, “Pow,” 2014. Oil, enamel, and sand on canvas, 30″ x 24″

*

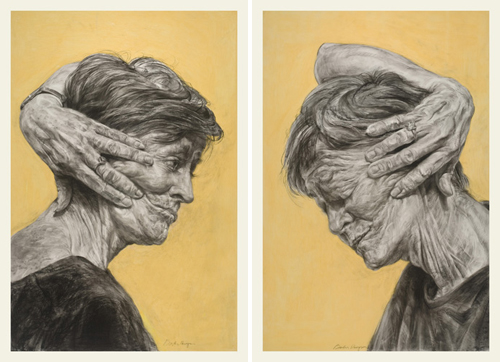

Mira Schor

Written during the Preoccupation: Activism, Heroism, and Art.

A week after the election, a cold heavy rain struck New York in a kind of climatic embodiment of our political shock and misery. Wearing the depressing New York winter uniform of black down coat for the first time of the season, huddled in the small doorway of a fortune teller’s establishment on Lexington Avenue, I waited for a bus and I thought about what I would write about for this final issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G.

My first instinct was to consider the role of activism in relation to being an artist but immediately my mind made a leap from activism to heroism. In the seconds between these two words, I was in tears as two stories I had been told by my mother since my childhood sprang to mind, one of political bravery, the other of personal bravery.

Please bear with me as I retell these stories, because they frame my ideas about the role of activism and the role of art and the artist in a moment of political necessity for activism.

To begin with, the story of personal bravery: my mother was very proud of her friendship with one of the most important Jewish families in pre-war Poland, that of Rabbi Moses Schorr, a religious leader, a historian, and the first Jewish member of the Polish Senate. The Schorrs (no relation) were kind, wealthy, generous, noble in bearing and behavior. At the outbreak of WWII Rabbi Schorr fled Poland towards the East where he was captured, imprisoned, and tortured by the Russians, dying in a Russian labor camp in 1941 (for more on the relation of Russia with Germany at that time, with interesting echoes in recent weeks, see here). Rabbi Schorr’s daughters survived the war, and I knew one of them well, Fela, a beautiful, kind, imperious, and broken woman, all at once. The story I was told by my mother though I never spoke of it with Fela herself, was that Fela and her mother along with Fela’s two small sons and her small nephew, all children under the age of 10, were imprisoned by the Gestapo in France. It was announced that children who were orphans would not be deported to Auschwitz so Fela and her elderly mother determined to commit suicide. Her mother took poison and died, Fela jumped out a window but survived and was saved and sheltered by doctors until the end of the war a few months later. She and the three children in her care survived the war.

The circumstances of the story were hard to believe, because it made no sense that orphans would be spared deportation and because of the cruelty of the promise, but the randomness of genocide was embedded in my consciousness as well as the emblem of maternal courage. [This story is true, you can read more here.]

The story of political bravery was embodied for me in the name Bartoszek. Franciszek Bartoszek was a friend of my parents from the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. He was a painter. And he was Polish. That is to say, he was not Jewish. This was central to the story, because that was a primary distinction my mother always made, a paradox at the center of her own patriotism. If she described someone simply as Polish she also was indicating that they were not Jewish, and it meant that Bartoszek’s bravery was motivated by more than personal survival. When my mother showed me the picture of him she always told me that he was a hero. She would tell me that he would risk his life just to bring a poor woman some small amount of butter. Her admiration for him was such that I have never been able to say his name without being overcome with tears, the emotional outlet of my more fierce and stoic mother. When I was able to research him online, the story was verified: Bartoszek was a renowned Polish patriot and hero of the Polish resistance, who died in a military action in Warsaw in 1943.

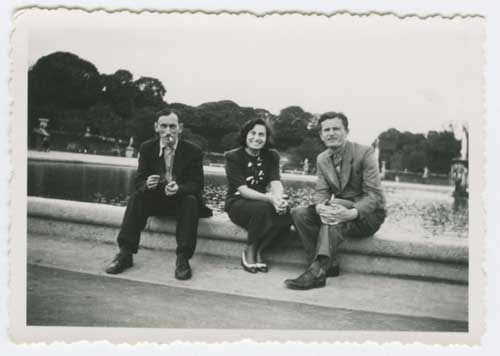

From l. to r., Ilya Schor, unknown woman, Franciszek Bartoszek, Paris, 1937.

I have photographs of him with my father. They are in a park in Paris sometime shortly before the war, most likely in 1937. The photos are very small, so I blew up a detail of one to try to decipher if one could see the courage to come in the face of the man in the time approaching the crisis. When I sent this picture to Luka Rayski, a Polish artist who translated for me a stele erected in Poland in Bartoszek’s honor, he wrote back that it was “so hard to imagine, those last pre-war years.” But I thought no, it is not hard to imagine that time. Not, I hasten to add, that I think another Holocaust is coming, yet we are in such a time, a time I call the Preoccupation.

![Photo detail, Bartoszek, Paris, c. 1937; Stele installed in Czarnow in 1964: Franciszek Bartoszek, “Jacek” [code name “Jack”] Born October 27, 1910 in Pieranie, spent his youth in Czarnow, Painter, Ardent Patriot, Colonel of People’s Guard, Died fighting Hitlerist occupiers, May 15, 1943 in Warsaw.](https://ayearofpositivethinking.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/MIRA-bartoszek-composite-image.jpg)

Photo detail, Bartoszek, Paris, c. 1937; Stele installed in Czarnow in 1964: Franciszek Bartoszek, “Jacek” [code name “Jack”] Born October 27, 1910 in Pieranie, spent his youth in Czarnow, Painter, Ardent Patriot, Colonel of People’s Guard, Died fighting Hitlerist occupiers, May 15, 1943 in Warsaw.

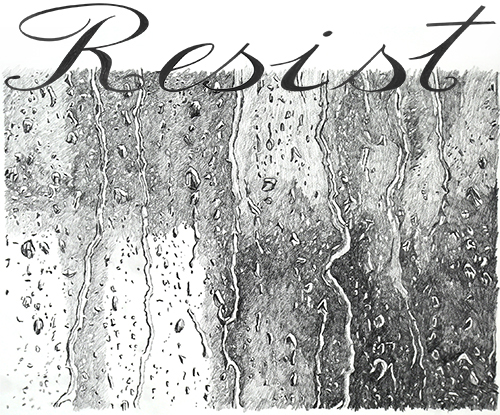

The sine qua non of resistance is that you have to be prepared to die for freedom, even though of course there is a big gap between marching on Trump Tower holding “Pussy Power” signs and prison or death.

If heroism is summoned as the ultimate necessity for freedom, nevertheless practically speaking most of us who care about what is going on are considering activism. It is quite striking how many people at all levels of society are mobilizing, from the political leaders of the state of California to artists in New York City mobilizing to provide imagery and objects for the Women’s March on D.C. and beyond.

Susan and I decided to start M/E/A/N/I/N/G in 1986, during the Reagan administration. I remember the precise moment—standing near the corner of West Broadway and Canal Street in December 1980, a month after Reagan had been elected and a few days after John Lennon had been killed—when I had realized that a switch had been flipped. Something was over. If I didn’t grasp the full import of the switch in terms of where we have arrived now, I experienced that every value I had been imbued with had just been turned upside down, including in art. The 1980s was a very contentious decade, highly polemic and divisive but perhaps because of that it was also a bracing and inspiring time during which there was a lot of activism, including responses by artists to the AIDS crisis, to urban gentrification, and to the backlash against second wave feminism. The Guerrilla Girls’ first poster appeared overnight in Soho and Tribeca in 1985, we published the first issue of M/E/A/N/I/N/G in December 1986. But despite the political polarization, looking back, no matter what happened in politics in the ’80s, I didn’t feel that the end of the world as I had known it was upon us and like Susan I had the optimism that comes from the energy of youthful mid-life and from doing something constructive. I was 36 when we started the magazine. I had been out of art school for 13 years, I had had a full-time teaching job in Canada and had given it up to move back to New York, I had had gallery representation and my first one-person shows in New York and had lost that. M/E/A/N/I/N/G opened up my community and gave me a sense of place in the art world. It has been the only sustained collaboration I have been involved with and the many things Susan and I have in common and the differences between us, as well as the small scale of our operation–two people, two issues a year during our hard copy days–all worked for me. And when we ended our print run in 1996, if anything I felt more optimistic and confident about my own life than I had when we started.

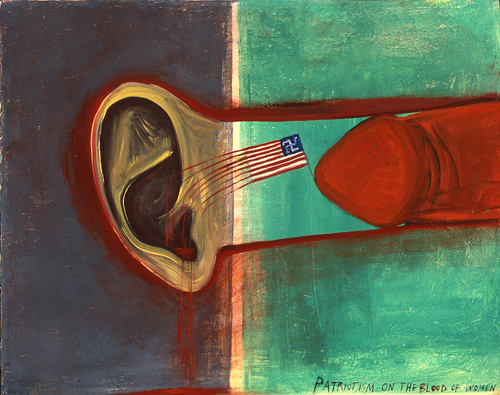

Mira Schor, “Patriotism on the Blood of Women,” 1989. Oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches.

The word of the day in the ’80s was intervention, actions specific to a moment and which did not necessarily seek to become an institution, though inevitably many cultural interventions did. I saw editing M/E/A/N/I/N/G as a kind of activism that I was able to engage in. In that spirit, our final issue is one of many artistic responses to the election and one which, as we have always tried to accomplish in M/E/A/N/I/N/G, is an open format, non-didactic environment for artists, writers, poets, art historians and critics to express their views in any cultural or personal register that means something to them, unrelated to market concerns. As we bring our project to an end after thirty years, we feel it provides one model for long-term activism within an art community. It is small potatoes in terms of major resistance to oppression but it is something that we could do then and now. It did enlarge our community and I think it meant something to the individuals we published, whether professionally or just because they were given the opportunity to think about something and express their views or tell about their work.

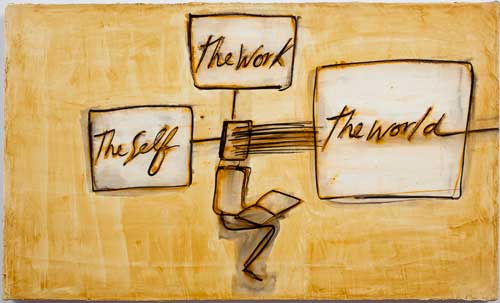

Mira Schor,” The Self, The Work, The World,” 2012. Oil and ink on gesso on linen, 18″x30″

My sense of necessity to understand the changes in culture in the ’80s led me to my critical writings and changed the course of my work as an artist, though my work has from the start had a political underpinning, primarily feminist. Some of my recent works have been visceral responses to the news. But I also think that other aspects of my artistic heritage and inclinations have political valence, though they might seem to be the opposite of political, that is, that the intimate, the modest, the private, though apparently recessive in a time of spectacle, can be construed as political acts. The artist is a filter between the world and the work, as I tried to indicate in a painting I did in early 2012 right after Occupy Wall Street as I was trying to diagram the place of the private artist during a political upheaval.

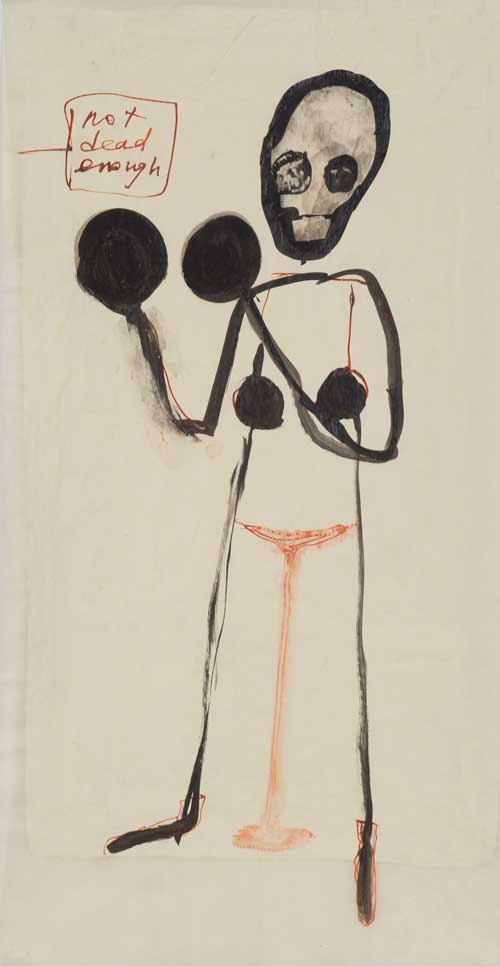

Mira Schor, “‘Power’ Figure: Not Dead Enough,” 2016. Ink and gesso on tracing paper, 17″x 22 1/2″

Since the election I’ve noticed the pleasure, indeed the gratitude people have expressed if someone shares a beautiful work of art on social media, not necessarily an outwardly political one. We recognize and value the works that use representation, figuration, and language to openly announce their political intentions, but a painting of a flower, a small abstraction, or an ancient vase can evoke as much humanity as anything more overt and the importance of such works as heroic human activity can be intense.

Susan Bee, “A Not So Still Life,” 2016. Oil, sand, and enamel on linen, 30″ x 24″

We conceived of this final issue a few days before I stood in that cold rain, during a visit right after the election to the Guggenheim museum to see the Agnes Martin exhibition. I was particularly interested in one small early painting of narrow vertical black and white lines of uneven length. In the face of the impulse, in response to the political atmosphere, for artists to start churning out Guernicas, the smallest of Martin’s abstract paintings packs as much of a punch about human endeavor and heroism as anything that would will itself to make a political statement. Though small, the painting has great tension and drama. To me it represents as much of the power of the universe as a model of the atom and it is heroic in the way that artworks can be, evidence of one individual artist’s search for perfection in a realm that seemingly has no specific utility to daily life.

Agnes Martin, Untitled, 1960. Oil on canvas, 12 x 12 inches. Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Gift of the Bayard and Harriet K. Ewing Collection

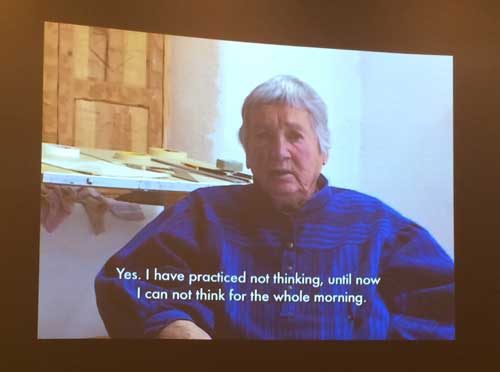

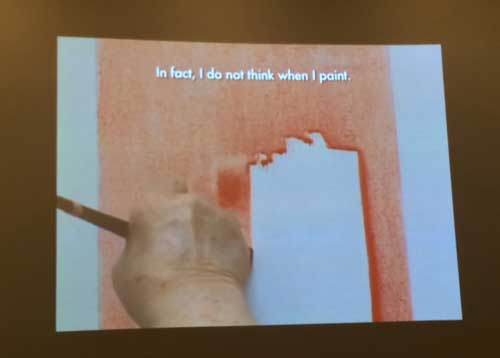

On our way up the ramp, we slipped through the keyhole-shaped door into the study library to watch two short films of interviews with Martin, filmed late in her life. It was very intimate to listen to her words in a small room. She spoke about her desire not to work from negativity, her efforts to empty her mind entirely when working, and about the role of inspiration.

In one film she is shown carefully applying a thin reddish pink wash to the canvas. The soothing concentration on this simple activity generated enough calm and clarity for me that suddenly the puzzle of how to celebrate the 30th anniversary of M/E/A/N/I/N/G which had eluded us earlier in the year was solved: I have a blog, we could use my blog as an initial platform for a spontaneous, short deadline, final issue. I looked at Susan and mouthed, I have an idea. So we end as we began, with a Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland “let’s put on a show” production. It is the small activism of giving a few people a place for their voice, and we are grateful to all the artists and writers who found the time to respond to our call.

***

Susan Bee and Mira Schor, M/E/A/N/I/N/G, December 1986-December 2016

***

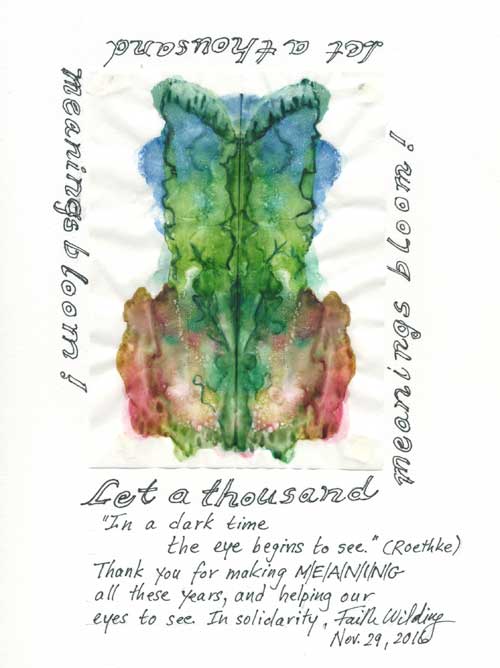

We would like to thank our many wonderful contributors to the final issue: Alexandria Smith, Altoon Sultan, Ann McCoy, Aviva Rahmani, Aziz+Cucher, Bailey Doogan, Beverly Naidus, Bradley Rubenstein, Charles Bernstein, Christen Clifford, Deborah Kass, Elaine Angelopoulos, Erica Hunt, Erik Moskowitz + Amanda Trager, Faith Wilding, Felix Bernstein and Gabe Rubin, Hermine Ford, Jennifer Bartlett, Jenny Perlin, Johanna Drucker, Joseph Nechvatal, Joy Garnett and Bill Jones, Joyce Kozloff, Judith Linhares, Julie Harrison, Kate Gilmore, Legacy Russell, Lenore Malen, LigoranoReese, Mary D. Garrard, Martha Wilson, Matthew Weinstein, Maureen Connor, Michelle Jaffé, Mimi Gross, Myrel Chernick, Nancy K. Miller, Noah Dillon, Noah Fischer, Peter Rostovsky, Rachel Owens, Rit Premnath, Robert C. Morgan, Robin Mitchell, Roger Denson, Sharon Louden, Sheila Pepe, Shirley Kaneda, Susanna Heller, Suzy Spence, Tamara Gonzalez and Chris Martin, Tatiana Istomina, Toni Simon, William Villalongo.

M/E/A/N/I/N/G: A History

We published 20 print issues biannually over ten years from 1986-1996. In 2000, M/E/A/N/I/N/G: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Theory, and Criticism was published by Duke University Press. In 2002 we began to publish M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online and have published six online issues. Issue #6 is a link to the digital reissue of all of the original twenty hard copy issues of the journal. The M/E/A/N/I/N/G archive from 1986 to 2002 is in the collection of the Beinecke Library at Yale University.

All of the installments of M/E/A/N/I/N/G: The Final Issue on A Year of Positive Thinking can be accessed by hitting the “older” button at the bottom of this post and they will be made available as a PDF on M/E/A/N/I/N/G Online.

![Jennifer Bartlett, A few days after the election a pop-up artist/therapy piece began growing in the Union Square subway station. Passersby were encouraged to write a message to the world [in response to the election] on a "sticky note."](https://ayearofpositivethinking.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Jennifer-Bartlett_Image_One.jpg)