I usually start my annual obligatory (imposed on me by the society I occupy, would not necessarily go otherwise) visit to the Armory Show at Pier 92 (the more intimately scaled “classic” side) before venturing into the maze of the more vast and high-ceilinged contemporary side of Pier 94. However yesterday by chance I started on Pier 94. Early in my journey I was standing with my friend Susanna Heller at a booth of a respected gallery telling her about seeing a show last year where the paintings in reality were so boring and empty that I could not find even the most banal compliment to offer to the gallerist. There was simply nothing to say about the work except that there was nothing to say about it. Upon which Susanna say, “Mira, do you remember anything about what we were just looking at?”

Ghastly huge work, all 689 inches wide of it: AIDA Makoto, “Jumble of 100 Flowers” 2017-2017. Acrylic on canvas, 79 x 689 inches.

As a living artist I have to admit that I would like to see my work well presented and represented at such an art fair, but by the end of my rather incomplete tour of Pier 94, my friends and I felt terribly tired, and further and more dangerously, dispirited about the whole idea of being artists.

Handsome paper mixed media work by Peter Linde Busk, “Everything, Everyone, Everywhere. Ends,” 2016, at Josh Lilley. In a way a perfect fair work: large and visible, eye catching, handsome, done with quality, hip and very effective mix of materials from low, cardboard, to craft, ceramic, but presented without context.

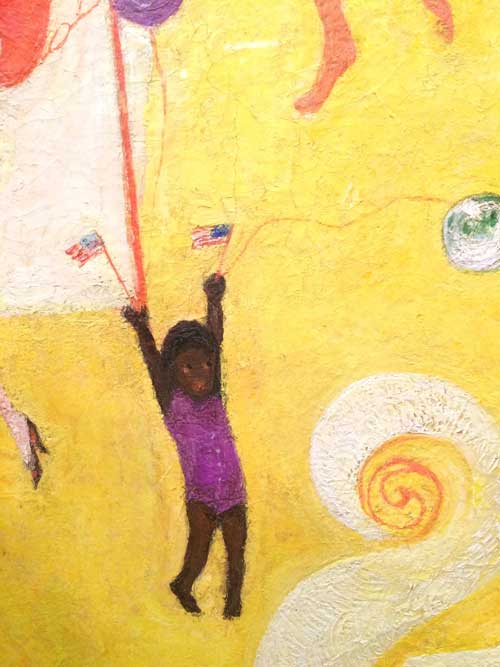

Florine Stettheimer, Asbury Park South, 1920, detail

Florine Stettheimer, Asbury Park South, 1920, detail

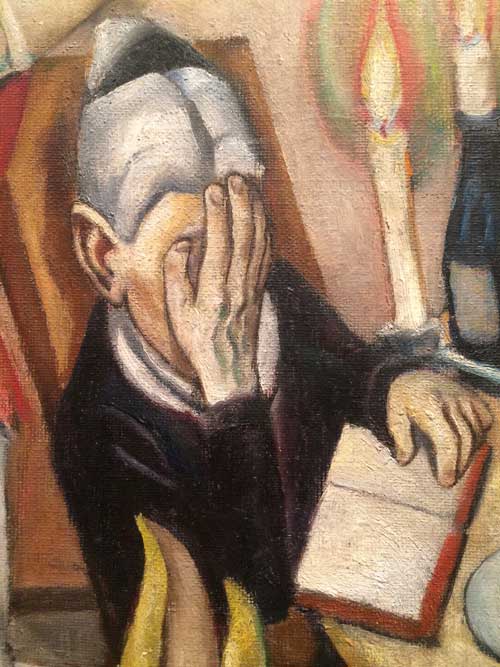

Only one work shone out of the blur–Florine Stettheimer’s masterpiece, Asbury Park South from 1920 (a painting scandalously deaccessioned by Fisk University in 2012) in a group exhibition organized by Jeffrey Deitch that orbited and created a lot of visual noise around it in a manner both consistent with Stettheimer’s aesthetic of excess and disruptive of the ability to properly view her painting. Many artists, including myself, have been influenced by Stettheimer, for various aspects or characteristics of her work, the narrative, the etiolated figuration, the gay sensibility in both senses of that word, the beautiful color, but in addition the works are so beautifully crafted and patented, the most beautiful colors, the most extraordinary surfaces, scumbled, dry, sculpted. This painting gave us a lift but we were still oppressed and depressed by the whole situation. Or at least I was.

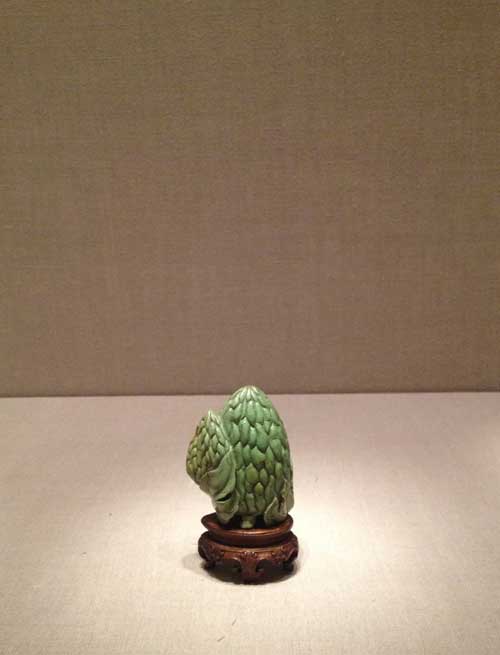

Then we left selfie land and we made our way up the stairs to Pier 92. First we came upon Kathy Butterly’s works, beautifully installed at Tibor de Nagy Gallery with Shoshanna Wayne Gallery. I envy Kathy, I love ceramics and porcelain and glazes and the way color works in such media, and thus I envy her because she makes beautiful things using these elements, things that give pleasure, that people want, which is something my parents who made beautiful jewelry also did, which I can’t say that I do–my work, critical, political, and intellectual,dreamy and personal, it appears that so far it is an acquired taste! I also relate to these works because they are modest in scale and invite the viewer into a relationship that is more intimate than most of the large shiny works typical of art fairs.

Kathy Butterly, Shoshanna Wayne Gallery and Tibor de Nagy Gallery

Kathy Butterly

Next we were drawn to a Native American painting on animal hide and discovered the most beautiful and engaging group of drawings by mostly 19th century and early 20th century Plains Indians, at Donald Ellis Gallery. The inventiveness of these drawings in the artists’ efforts to depict using very reduced means (am referring to the works on paper with pencil and sometimes ink, materials which appear to be what was available to them on reservations) what they were seeing and experiencing was absolutely inspiring.

SHield and cover, Crow, Northern Plains, c.1870, buffalo hide and paint, Donald Ellis Gallery

Shield and Cover, Mescalero Apache, Southern Plains c.1880, buffalo hide and paint, Donald Ellis Gallery

Plains Indians, drawing, Donald Elllis Gallery

Plains Indians, late 19th century, Donald Ellis Gallery

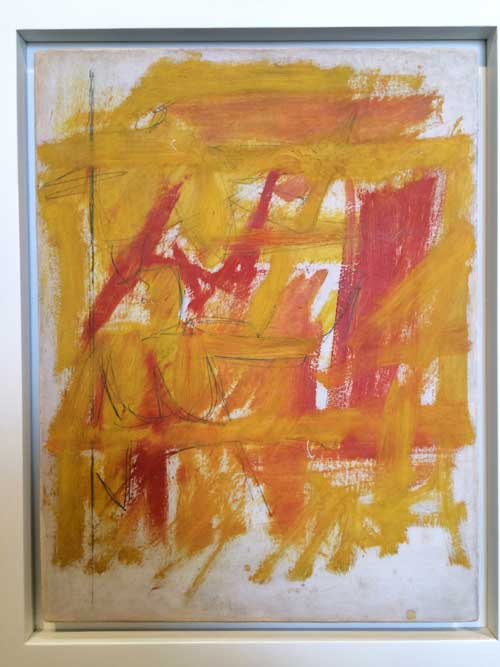

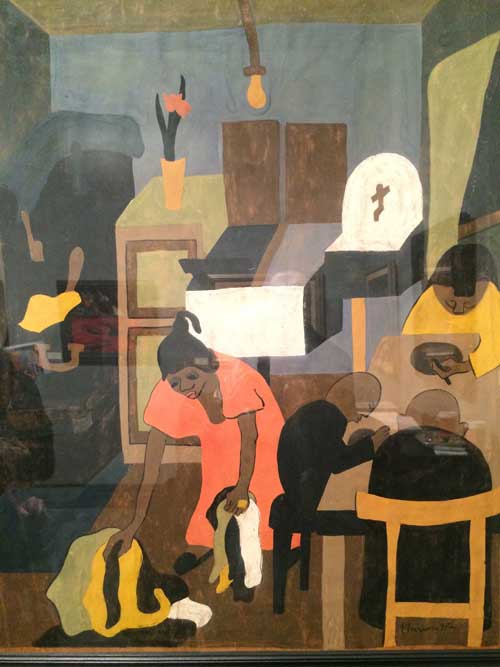

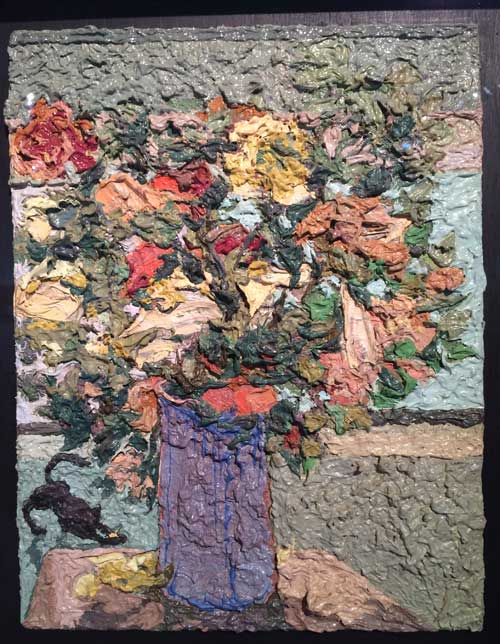

I discovered a few Jack Tworkov works in a couple of galley booths: his poetic elegance and measure always sing out to me. Next an exhibition at Jonathan Boos of Jacob Lawrence works from the 30s,40s, and 50s, beautiful color, tenderly observed details, jagged forms. A small richly impasto Jess vase of flowers on a thin panel, an intense Ossorio.

Jack Tworkov, oil sketch, Hollis Taggart Gallery

Jacob Lawrence, Interior (Family), 1937. Tempera on paper, 30 3/8 x 25 1/5 inches, Jonathan Boos Gallery

Jess (Collins), Petals of Paint, 1964. Oil on plywood, 16 x 12.25 inches.

Clearly when you see older work now, it is the product of a system of filtration and of intensification, the dross of the time period has been filtered out and the richness of meaning has intensified over time as more historical information has been pressed into the work by the passing of time, but I also thought that my friends and I are perhaps the last generation that can really understand this work in a living way rather than an archeological way: we were brought up with the values of materiality, form, style, process, search for truth (belief in some kind of truth or honesty), with the analogue, the handmade, the personally developed (not as recipes that are copied and reconfigured endlessly but without the struggle that went into the initial works, as in zombie formalism) — at time when artists sought within the work rather than researched before the execution of the work. It often feels that our knowledge sets us apart–in a bad way: we can’t put our knowledge forward in the current mode of the sampled and reprocessed–often done very very proficiently–because we absorbed the initial relation to making of these older works, made by our parents, teachers, older friends. [I should add that often I am led to rethinking this impression, because at the same time there is so much art being made by young artists all over the world, with after all as much desire and imagination as any other previous generations brought to their work, yet, as Susanna pointed out, that may be truer when you see the work online, then one sees the work in person (as opposed to on Instagram, for which so much work is now both unconsciously and consciously created) and its potentially alienating synthetic nature often reasserts itself.

I have often quoted my mother’s words upon seeing a show at the Whitney on Picasso’s influence on American art. She was then 95 and, as it turns out, only a few weeks from her death, and she found it hard to stand for a long time, but in the taxi home she said, “it’s the kind of work that makes you want to go home and work.”

I should say that over my life as an artist (and I include in this my work as a writer about art) I have often gotten as much energy from work I “hated” as from work I loved, because the antagonism pushed and liberated me to move forward and live in my own time: such a relation may still be operative, but I suspect that the depression my friends and I felt comes from seeing now in a lot of art fairs work we just saw five minutes ago in our MFA student critiques, and from the fact that even those significant challenges to our world view are by now kind of old as well, though they may not feel that way to the people doing them or the collectors fawning over what seems to be the latest thing, really just by the latest person.

So Pier 94 made us want to give up on art making, with a few exceptions (some contemporary + Stettheimer, who died in 1944), Pier 92 made it possible to want to go home and work in the studio.