A word enters the culture and as its usage widens, its ideological meaning become clearer. The usage of the terms “creative” retroactively applied to a 1970s situation made me post a statement on Facebook which clearly struck a chord in my Facebook community. The conversation this provoked I think is worth sharing here, something I have done a couple of times on A Year of Positive Thinking. I have edited the thread but not the comments. The conversation is ongoing.

I’m concerned that the term creative, used sometimes as a noun, “creatives,” is seeping out of trendy promotional text about young “creatives” moving into new neighborhoods etc and into mainstream art text. Instead of artists, you have “creatives”–it’s similar to the distinction between being considered “artistic” in high school and actually being an artist but now transformed into a marketing category of dubious character.

Carl Ostendarp: I feel the same way, Mira– I’m not sure this is at all helpful or fully thought through, but I’ve been thinking that this new usage is predicated on the notion of creativity as a problem-solving activity, (maybe somewhere between design and the expanded definition of curating)–and I think of art-making as problem finding.–come to think of it, I think this may relate in some way to your earlier post with the Joan Brown interview about distinctions between art as research and as a process involving praxis.

MS: Carl, that is a very good way of describing the distinction between terms and identities. It’s a word used to create a marketing demographic and there is a techno design curating orientation, with a debased concept of curating.

Millie Wilson: and what a phony word! creatives are “trending” which is another word that functions similarly.

MS: My post was prompted by the retrofitting of the term in a description of the downtown art world of the 70s as the “1970s downtown creative scene.”

Michael Waugh: Not only that but the blurring has the effect of subsuming all creative activity into a corporate rubric. The critical stance that distinguishes art is effectively negated by the category “creatives.”

Stefany Benson: I’ve heard the term “makers” used also to be inclusive of all the people who pursue creative endeavors like inventors and even product designers. ??

MS: exactly Michael! that’s why it grates so much. Yeah and “makers”–that’s more complex for me because “making” , in scare quotes, denotes the kind of art that is thought to be less intellectually valid than certain types of art associated with research as an institutional art type, but too long to go into that, I mentioned in another post today a book I’m reading called Troubling Research which is is quite interesting in that regard. So “makers” is in scare quotes in the art world, but fits in with “creatives” as a corporate trending group.

Dm Simons: It is about marketing, advertising, a straddling trigger that encompasses market strategies—similar to the use of “properties”, as a ball-of-wax term for artists and art work.

Cassandra Langer: Not sure exactly what disturbs you about the term. Many 50 something and under use it to distinguish themselves and their activities as other than a 9 to 5 job(although now that designation seems obsolete). Like the term queer it may take a little getting use to and refining. To be an artist and live that life is something specific that could fall under creatives in their minds if not an older generations. Mira are we dating ourselves as language grows changes and adapts?

Eric T. Banks: Cassandra, The term “creatives” tends to lump in all artistic enterprise whether done for true artistic purposes (i.e. search for meaning) or any other thing from set design to interior decorating. I very much see Mira’s point here and am irked by it as well. If it is a “generational” thing as you infer than it should be a learning moment for one older and wiser to illuminate those younger and hipper to the distinction. Soon they’ll go back to “artsy.”

Andrei Molotiu: “Creatives” is a term to flatter TEDx attendees

Carol Bruns: “creatives” is used by business to borrow prestige from artists. if artwriters call artists “creatives” they are lumping them with advertising people and commercial enterprises.

Edward Winkleman: I’ve taken to using it when discussing people who want to pursue a career for which the paying jobs are extremely rare (writers, dancers, actors, artists [which for me always connotes visual artist], musicians, etc.). I see your point, but would welcome an alternative.

Tom Knechtel: I’ve felt that it has a disturbing undertow of Alphas versus Deltas. Besides, it’s just sloppy. Some of the people using the term are the least creative people imaginable.

MS: Edward I think your question answers itself: being a writer, a dancer, an actor, a visual artist, a musician, a designer, are designations of what a person does well and is committed to, whether or not they get paying jobs for these practices. Those are the alternative terms: I’m a painter, an artist, a writer, an actor, a playwright. People sometimes engage in more than one type of art practice, but that’s different. “Creatives” suggests a conformist, marketable type of pseudo-nonconformism. It replaces dilettantism, which was generally derogatory and wasn’t as much of a commodity. Of course some people who might be lumped in this new category are actually serious artists in a specific field and will outlast this terminology.

Tom I was thinking of Brave New World just this morning, if not exactly on this track. I was thinking of my mother’s politically prescient and astute statement to me, in her 90s, watching the nightly news: “so in America soon it will be the corporations and the slaves.” Maybe “creatives” are the attractive end of the wedge.

Joanne Mattera: Shiver

Nancy Evans: creativity is not confined to artists, but artists do have special problems and needs that make it irresponsible to group all “creatives” together … plus I think they mean by “creatives” smart computer programmers.

Heide Fasnacht: It is indeed a marketing category but not dubious. In Detroit, for example, it is used to describe young entrepreneurs coming in to “rescue” the city. They are misguided in believing in “solutionism”. Typically, they are not artists. I believe they are very cynical.

Henry Bogle: I have no problem with the term. ‘Artist’ also has issues with presumption, generalization, and contextualization in the postindustrial/digital era.

Kristina Newhouse: Imagine how we curators feel now that everyone is a curator. The circular game of patting oneself on the back is now made complete. Everybody is a creative AND a curator.

Lori Ortiz: Creative (noun) used to be the term for those in advertising responsible for writing ad copy, coming up with the campaign ideas ( think Don Draper) as well as those who penned or penciled the accompanying ‘art.’

Sam Erenberg: Mira, you use the term “practice,” which bothers me as much as the term “creatives” bothers you. Twenty years ago, we ascribed the former to law and medicine. “Practicing” the violin does not make one a “creative” musician.

MS: Sam it’s true! Yet another case of terminology creep. I do use “practice” and probably other words I used to find annoying, and I will probably use “creatives” but I think always in scare quotes.

…

Scott Davis: Last year someone on Facebook pointed me to the origin of “Creative” as a demographic designation. …I was shocked to see that “Creatives” did not necessarily refer to artists at all. “The creative class includes people who work in science and technology, business and management, arts, culture, media and entertainment, law, and healthcare professions.”

Eve Andrée Laramée: To my way of thinking and observing, the term “creatives” connotes gentrification and marketing of objects and space (consumer products and real estate.) It can also suggest a luxury class of those who have the leisure time (and possibly family money) to “be creative” rather than be a laborer and/or wage-earner. Sometimes it is used to describe opportunistic “entrepreneurs” or “developers” that can be parasitical to the artists and makers of culture. The term “maker” may be a an updated version for “inventor” – to replace terms such as crafts-person, or tinkerer (in the best sense of tinkering…I consider tinkerers geniuses!)

Steve Locke: …It’s the language of neo-liberalism slithering into art.

Jenny Dubnau: Oh god do I ever agree. It is also the coded language of gentrification: “creatives” always pay more rent than artists.

Julian Jackson: Plus it turns everyone else into non creatives? Enough divisiveness as there is.

Noah Becker: it’s a term used in real estate to describe artists during the gentrification of neighborhoods.

Dooley La Capellaine: I worked as a “New Media”consultant on Wall Street and was really nauseated by this term of expression. They blew the bubble and Ihave survived the “creatives” nonsense.

Susan Silton: I think “creatives” originally derives mainly from advertising, i.e., the distinction made between those responsible for coming up with campaigns (copywriters, art directors) and account managers. There have always been simultaneous artworlds, but now cultural production has proliferated because of the ease of technology, and art has increasingly been packagedlike advertising (not to mention commodified.

Richard Kooyman: Like many neoliberal constructs the use of the word appears genuine and practical but has an underlying political purpose. It wasn’t Richard Florida who originally thought up the concept but actually Charles Leadbetter who wrote much of the neoliberal ideas behind Tony Blair’s New Labor Policies. They invented a way for government to be held less socially responsible by declaring everyone a creative individual and everything a potential market. The problem isn’t just that it’s a lazy term. The problem is that it turns the intrinsic value of Art into just another market.

Camille Eskell: The thrust in education now is being a “problem-solver” to think in creative ways because they do not know what the job situation is going to look like in the years to come for young people now. Students are to tackle “read – world problems” in the classroom so they can be better equipped for the future. Ironically, the push is for STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) in stead of STEAM which includes the arts. Interesting that the progenitors of this idea of being creative left out those who are essentially creative. Art is still very much misunderstood by the linear – thinkers in education (and the outer world); most think it is child’s play and do not have the foggiest notion that a true thinker and creative person uses all of themselves, sequential and holistic approaches and applies the practical and the sensory, the intellectual and the emotional in one fell swoop. Plus I think the term “creatives” is appealing to the young who will soon become the work force and ever greater consumers.

Nancy Buchanan: I recommend looking at Martha Rosler’s analysis of Florida’s ideology. The transformation of almost everything into a commodity, and everyone into an entrepreneur seems to be related to the softening or substitution of many terms. Like “gallerist” for “dealer” (dealer being, in my opinion, the more honest descriptor). And–who is happy about being part of the problem (e.g., the “Creative Class” speeding gentrification & displacement)?

And capital for Capital, not necessarily for “creatives.”

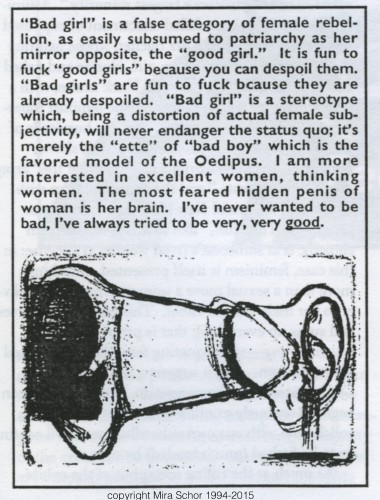

Thanks to Millie Wilson for posting this image (and link). Thanks to all of those who participated in this conversation thread and did not object when I asked if I could transfer it here.