Two painting exhibitions currently across the street from each other on West 25th street challenge any notions one might still harbor about the greater value of being “younger than Jesus.” By some fortuitous coincidence just a few steps separate “Joan Mitchell: The Last Paintings” at Cheim & Read from “Matta: A Centennial Celebration” at Pace Gallery and each show explosively refutes any notion of youthfulness being the province of the young while giving new life to the phenomenon known as “old age style”–used to distinguish formal characteristic of late works by Titian, Rembrandt, or Cézanne, where the artist just wants to get to the heart of the matter and sloughs off all the fine finish he had needed to impress his audience in earlier years.

Before I go any further, I should say that for some reason, when I was a very young artist, before I went to art school, one of my term papers as an art history major at NYU was on old age style, in the works of Renaissance and other artists. At the time in my own early paintings, I was influenced by Northern Renaissance paintings, by surrealism, by Indian miniatures, so for the most part the paintings I loved had a tightness and perfection to them. So I can only wonder why I was in this very early stage of my own work life so taken by the characteristics of work done at the other end of the bracket of a life of art making, when tightness of line and surface would yield to the pressure of working without concern for perfection or control. Indeed ever since then, I always seem to challenge myself to move towards a looser, wilder, more entropic approach to artmaking.

The phenomenon of old age style seemed almost inversely applicable when considering expressionist painting. Take the phases of Willem de Kooning’s work: in the current exhibition at MoMA there is an early still-life drawing, of a type that, according to the wall-text, a friend recalled might take him a year to execute, building up the realistic rendering practically one atom of matter at a time, then there is the Ingres-like delicacy of representational execution of the Portrait of Elaine, followed by the early mature work of the figures of men and women just turning from representation to abstraction as if a giant delicate hand were shifting the outlines like sand, to the great abstractions of the late 1940s, Excavation and Attic, still controlled, calibrated, worked, to the explosive expressionistic paint application of the Woman series–but, with the notion of old age style in mind, then what? If at an earlier time, that loose approach would have marked an old age style, de Kooning had much farther to go, to return, in his old age, to his own contribution to such a style–abstraction and surface somehow scoured of incident and even gravity, smoothed, clarified, almost bleached by time.

I’ve always felt that Joan Mitchell‘s paintings from the 1950s are among the best abstract paintings of that period. Although there is a clear relation to nature in the forms and colors, at the same time those paintings, including Ladybug (1957) at MoMA, have a bold confidence in the sculptural individuality of each stroke of paint in a manner which anticipates the post-minimalist approach of painters such Joan Snyder. The unpredictable, rich yet uningratiating dimensional materiality of the paint strokes in these paintings, and the density of mark making has generally been of greater interest to me than the late paintings, some of which were on view in Mitchell’s 2002 retrospective at the Whitney Museum–I saw these as too big, too empty, too facile, without tension.

Joan Mitchell (1925-1992), Ladybug, 1957. Oil on canvas, 6' 5 7/8" x 9' (197.9 x 274 cm). Purchase. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Joan Snyder, Summer Orange, 1970 oil, acrylic, and spray enamel on canvas 42" x 96"

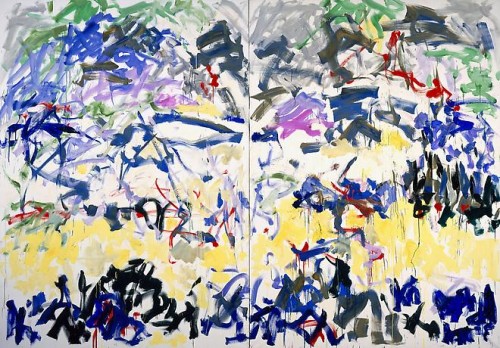

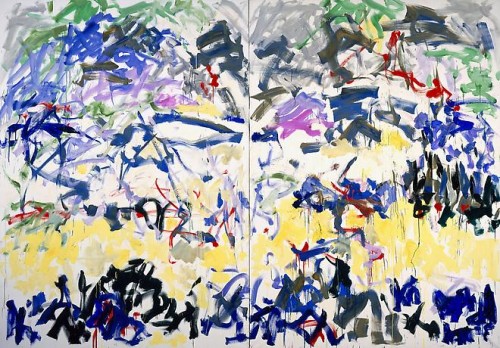

Perhaps the temper of the time has changed–sometimes one needs certain things from art which didn’t appeal earlier. But the paintings in the current show at Cheim & Read are a pleasure. The paintings, often diptychs, feature often large gestural strokes, they are speedy, speeding, they flow freely, yet with an important density, which I had missed in the later works at the Whitney. A painting such as Beauvais (1986) is a beauty, as is River (1989): the marks are loose and quick but orchestrated with a complex relation of similarity but dissymmetry between the two panels of the diptych. The painting appears loose but not lax, with small, sharper, deep red strokes interrupting the idyllic rural atmosphere with a more foreboding intimations of mortality.

Put another way, if you associate youth with vibrancy, color, energy, and brightness, then the earlier works by Mitchell, done when she was young, are more complex, perhaps more tortuous, and more encrusted, in a sense dirtier, they look “older” (and not just because they are older physically), whereas, by the same criteria, the last paintings up at Cheim & Read look “younger.” The palette is both the same and yet brighter, the white ground bigger and whiter–the emptied out quality thus being a marker both of youth and of age, depending on how you look at it, but certainly one could make the case that she was so much older then, and then was younger than that at the end.

Joan Mitchell, from the series "Fremicourt Paintings 1960-62," exhibition at Cheim & Read, 2005

Joan Mitchell (1925 - 1992) River, 1989, Oil on canvas diptych 110 x 157 1/2 inches each panel: 110 x 78 3/4 inches

One of the most remarkable paintings is Untitled (1992), the year of Mitchell’s death: again a diptych, this painting has an unusual composition, with all the action taking place in a horizontal band calligraphically rushing and tumbling across the middle of the two canvases’ white field, with a dominant ultramarine theme, bold gestures underscored by more delicately calligraphic lines, including again the thin deep red lines.

Joan Mitchell (1925 - 1992) Untitled, 1992, Oil on canvas diptych 102 3/8 x 157 1/2 inches

These paintings, from the year of her death, are expressions of freedom, clarity, and insistence or necessity.They are curiously joyous, considering that the artist was in poor health, suffering from cancer and other crippling afflictions.

Across the street, again, joyfulness, in the expansive, enormous late paintings by Matta (Roberto Matta Echaurren, 1911-2002). These works are representative of the artist’s characteristic forms, figurative, mechanistic, biomorphic. For young artists, impressed by spectacle and influenced by graffiti, the Matta show is also an important object lesson in what age can bring.For example Architecture du Temps (un point sait tout), done in 1999 when the artist was eighty-eight years old, is a fantastic huge black and white painting which relies mainly on an open framework of thin black lines within white paint and thin black washes. In French the expression “un point, c’est tout” is kind of verbal super punctuation, literally, one point is all, which is to say, that is it, there is nothing more to be said; “un point sait tout” sounds the same but means one point knows everything, which, as the subtitle of Architecture of Time, is a very telling pun and a sharp commentary on the making of art in old age, as well as on the power of line, the power of a point in space.

Roberto Matta, Architecture du temps (un point sait tout), 1999 oil on canvas 14' 11-1/2" x 21' 9-1/4"

Roberto Matta, L'homme descend du signe, 1975 oil on canvas 13' 5-3/4" x 27' 4"

Matta’s confidence in art is expressed in another even more contemporary-looking and even more enormous, twenty-seven foot wide, painting, L’Homme Descend du Signe (from 1975, when the artist was just a baby at age sixty-four). Another pun: “Man Descends from the Sign” (instead of “Descend du Singe,” man descends from the monkey). The painting is positively gaudy, with acid purple the main ground for sharp dagger like forms, which could easily be transposed to become tags. It is a great bridge between museum-scaled surrealist painting, architecturally-scaled mural painting, and city-scaled graffiti. The Fall (Autoritratto d’ognuno) from 1991 is another beautiful painting, again, an opening up of Matta’s earlier characteristic surrealistic web of drawing based biomorphic shapes. The painting is graced by a lovely spray of color, orange, the color of fall, a kind of ecstatic naturalism. (The largest paintings, oil and acrylic on unstretched canvas, are mounted on the wall framed by a thick white wood border, a very successful presentation).

If you associate energy and size with the brash ambition of youth, then these later and late paintings by Matta are also “younger” works than his earlier paintings from the surrealist period, which were tighter, more intricate and complex. At the same time the looseness and freedom of materiality in the later work is emblematic of old age style. At the very least, these works all confound one’s traditional expectations regarding age and the artist.

Roberto Matta The Fall (Autoritratto d'ognuno), 1991, oil and acrylic on canvas 10' 3-1/2" x 17' 1-5/8"

The images don’t do justice to the works, paler (in the case of Matta) and without the impact of either scale or surface. Go see the two shows.

Also seen the same day, down the block from Pace Gallery, in the show at Lennon-Weinberg Gallery, “H.C. Westermann: The Human Condition, Selected Works, 1961-1973,” some early drawings by H.C Westermann (1922-1981), done (as I overheard the gallerist explaining) when the artist was in the hospital being treated for testicular cancer–which he survived: his wife had brought him some crayons and paper, and he worked on a group of small drawings, some in the artist’s characteristic graphic, cartoon-related style, some in a more abstract and less over-determined mode–after he recovered, these were packed away and never shown until now. I recommend the drawing entitled Sun Coming Up Over New York, (1961), incredibly delicate, nearly abstract.

Although this was not an old age style work, it made me think about what it means to make art when you are very ill, or at the end of a long life. No matter your degree of success, if you are still making art at age 88, or ill from cancer, you cannot only be making art for show, for ambition, competition, legacy. You are making art, as Jack Tworkov noted about painting, “to save your life.” It’s great to see such art, when we are often confronted by art whose motivation is not necessarily based in that kind of internal necessity.

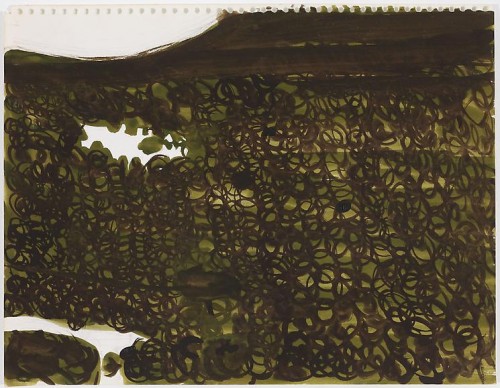

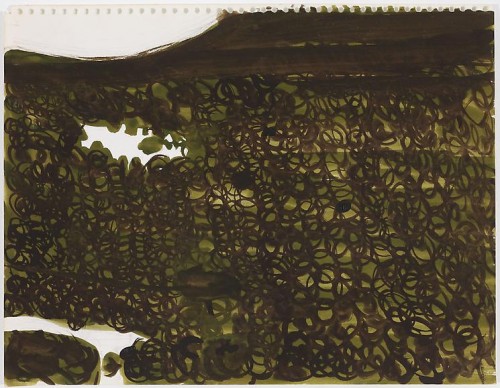

Richard Artschwager Untitled ca. 1950 watercolor and graphite on paper 10 7/8 x 13 7/8 inches

Richard Artschwager Untitled ca. 1950 watercolor and graphite on paper 13 7/8 x 10 7/8 inches

Earlier the same day in Chelsea, I saw Richard Artschwager’s show at David Nolan (show closed December 4). In this show, small abstracted landscape works on paper, all done in 1950, were shown along with new similar but larger works, paper mounted on soundboard, in which the artist returns to the Western landscape of the earlier series. One tends not to think of Artschwager in the same breath as Charles Burchfield, but the 1950s works participate in the great tradition of American ecstatic landscape, filtered through a calmer structure that is characteristic of Artschwager; some of these works are also reminiscent of Georgia O’Keefe’s earliest abstract landscape watercolors as well as of Agnes Martin’s early works on paper. In these earlyworks there is a lyricism, a tenderness of touch, of surface, and content, while the more recent work of the same subject matter is tougher, sharper, bolder and more imposing materially, thus proposing another kind of youthfulness in older age though the return to landscape or nature as a thematic seems to bracket the period of cooler irony of Artschwager’s most noted works, emerging in the era of Pop Art and continuing through the era of appropriation art.

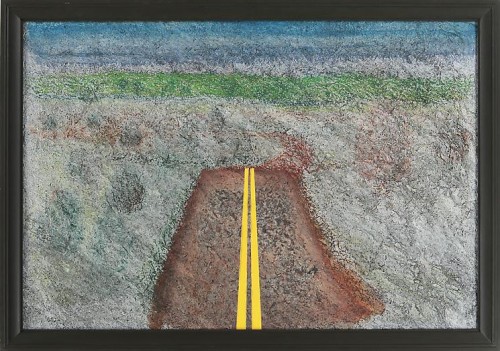

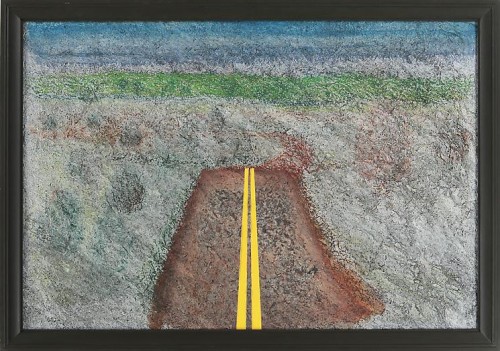

Richard Artschwager Landscape with Median 2011 acrylic, charcoal and laminate on handmade paper on soundboard 35 1/2 x 49 3/4 inches

Unlike both Mitchell and Matta, Artschwager is a master of reticence and modesty, combined with a subtle but wicked deadpan. In these returns to landscape, the deadpan turns to a subtle meditation on the progress of life: in Landscape with Median, from 2011 (Artschwager was born in 1923), the yellow double lines on the road end mid-picture: these lines are very bold, hard-edged, bright colored, and sharply sculptural, set into a much softer ground: maybe there is just a dip in the road ahead, or maybe the road comes to an end–in a 1950 watercolor, the road continues like a fragmented ladder though land that is barely indicated. These works, early and late, state that the artist who stays alive in his or her mind and studio is always caught mid-path.