Next Friday May 21, there will be a symposium at MoMA on Art Institutions and Feminist Politics Now (where “an international group of artists, writers, curators, historians and activists discuss the impact of recent debates about art and feminism on exhibitions, collections, pedagogy, and cultural politics.”). This continues a series of major feminism-related events held at the museum including The Feminist Future: Theory in Practice in the Visual Arts, a highly charged two-day symposium held at MoMA in January 2007. To hear some of the panels and presentations from the 2007 symposium: in addition to the material archived on MoMa’s website of that event, there is a comprehensive audio archive on ARTonAIR.org (you have to scroll down but will find the entire conference). Next month will see MoMA’s launch of its publication Modern Women: Women Artists at The Museum of Modern Art. In addition to these events at MoMA, what sounds like an interesting, interactive program will take place at the Brooklyn Museum on May 22, Making Ourselves Visible, with participants including Hilton Als, Emily Apter, Johanna Burton, and others.

There are currently several small one-person and group exhibitions of women artists and installations of discrete works by women artists scattered around MoMA although perhaps secreted might more accurately reflect the stealth approach to the serious engagement with curation, presentation, and acquisition of works by women artists that the museum is currently engaged in. There is a lot of very good work by women artists on view at MoMA right now, although aside from Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present, you would hardly know about many of these shows from the signage in the lobby, and certainly would not know to look for or understand the import of some individual installations.

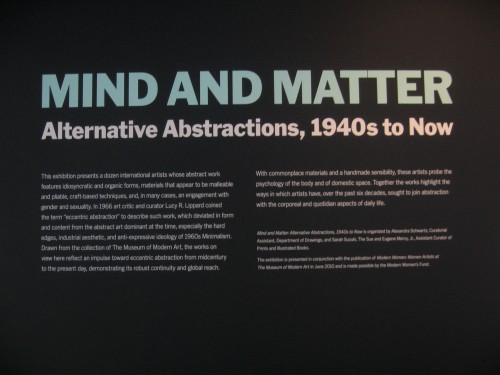

Wall signage, MoMA Lobby, May 6, 2010

The shows include Mind and Matter: Alternative Abstractions, 1940s to Now, Lee Bontecou: All Freedom in Every Sense, Performance 7: Mirage by Joan Jonas, and Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography, (and look for Experimental Women in Flux, opening in August).

The way I became aware of these exhibitions had an Alice in Wonderland Secret Garden feel to it that reflects the stealth approach.

First, during one recent visit, I noticed a large painting previously unknown to me, hanging in one of those out of context, no-man’s land spaces near the escalator bank, on the 3rd or 4th floor.

Lee Lozano, Untitled, 1963. Oil on canvas, two panels, 7' 10" x 8' 4," Collection The Museum of Modern Art

There is some ironic justice to the isolated presentation of the Lozano work: her decision to “boycott” women, taken in the late 1960s and maintained for the rest of her life, is legendary so being placed in the context of women artists would be anathema to her. In fact the painting presents an object lesson of why you can’t assume the gender of the artist from an individual work, since it has every sign of what generally would be consider the epitome of masculinity: the subject, the size of the work, the scale of the image, even something boldly un-ingratiating about the dry paint application. But anyway, there was the Lozano painting, and why had I never seen or at least noticed it before, and what was it doing there?

Then, another day at MoMA, as I was making my way to the Cafe on the 2nd floor, I noticed a curator I know slip into an exhibition hall. Curious, I followed her, sort of like following Alice down the rabbit hole, and I found myself in a large room (where Monet’s Waterlilies were earlier this winter).

Yayoi Kusama, Violet Obsession, 1994. Sewn & stuffed fabric over a rowboat and oars, 43 1/4" x 12' 6 3/8" x 70 7/8", collection MoMA, in Mind and Matter

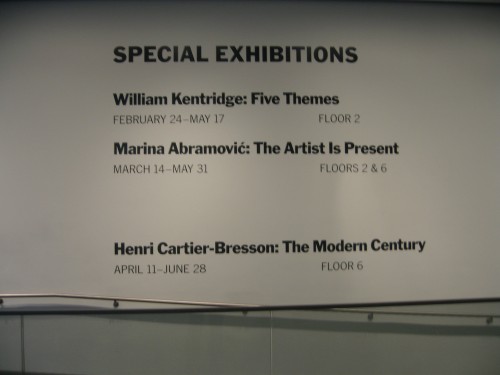

In the center was a full size row boat made of purple silk phalluses, unmistakably a Yayoi Kusama, there were elegant minimalist works by Gogo, an embroidered patchwork cloth book by Louise Bourgeois.

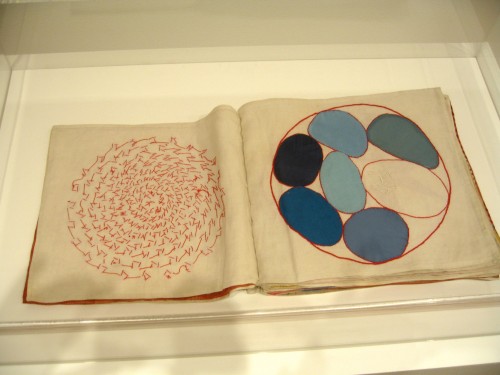

Louise Bourgeois, Ode à l'oubli, (2002). Fabric book with hand-embroidery and lithographed cover, page (ea. approx.): 11 3/4 x 13"

Louise Bourgeois, Ode à l'oubli, (2002) detail

Louise Bourgeois, Ode à l'oubli, cover, (2002). Fabric book with hand-embroidery and lithographed cover, page

The artists were all — women? Where was I? I went outside again to check the title, “Mind and Matter: Alternative Abstractions, 1940s to Now,” but nowhere in the introductory wall text is there any indication of the fact that all the artists in the show are women although of course it is evident from the list of artists.

Mind and Matter, Alternative Abstraction, 1940s to Now, MoMA wall text, May 2010

I was particularly struck by a strong artwork in the show by a Polish artist I was unfamiliar with, Alina Szapocznikow (1926-1973). The work, Belly Cushions (1965), made of 5 polyurethane foam pillows molds grouped on a low pedestal, has a strong presence: the dark rich color and leathery patina drew me across the room and then there is something compelling and yet strange about the shapes: the scale is indexical, yet the torso truncated so that sexual indicators are lacking — the work has the intensity of one of Nancy Grossman‘s torso sculptures from the same period without as overt tropes of sexuality — and the flat back of each form repels a unitary reading of these as molds from real bodies.

Alina Szapocznikow, Belly Cushions, 1968

Why are these particular abstractions alternative? Because the artists are all women? OK — positive thinking — I won’t go there. For more alternative abstraction, look to Lee Bontecou: All Freedom in Every Sense on the fourth floor, in an open space between an entrance to Painting and Sculpture II and a view of the museum garden.

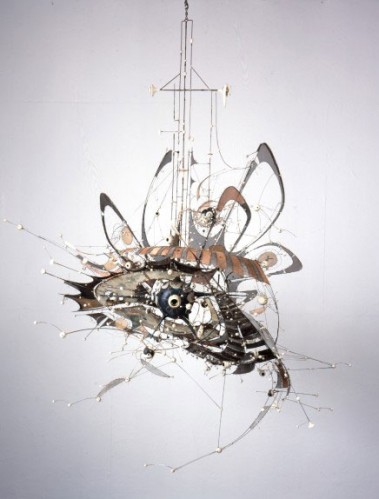

Lee Bontecou. Untitled. 1980–98. Welded steel, porcelain, wire mesh, canvas, wire, and grommets, 7 x 8 x 6'. MoMA © 2010 Lee Bontecou

The centerpiece of the show is an untitled hanging sculpture that Bontecou worked on for nearly twenty years. It has an eerily uncategorizable quality, in addition to being extremely difficult to photograph: it is an ethereal, jewel-like, surrealism-inspired curio — the connection to surrealism links it to many of the works in Mind and Matter: the utility of surrealism as a matrix for work by women artists is an important subject of modernist and feminist art history (though on the other hand the resonance to works by Calder or Tanguy puts into some question the subtitle of Mind and Matter — Alternative Abstractions — in relation to a women artists only grouping).

The most interesting work for me was the least branded. These are beautiful soot drawings. My snapshots could not capture the soft surface, I really recommend spending some time with them: Untitled, 1958, Soot on Paper is a very minimalist exercise in darkness, a black field divided by two central barely lit horizontal lines, one straight across and hard edged, the second curved and soft. Bontecou’s use of soot came from her quick awareness of the aesthetic usefulness of an accident in the mechanics of sculptural process: “While on a Fullbright Fellowship on Rome in the late 50s, Bontecou accidentally made what became one of the most crucial discoveries of her career: she adjusted the oxygen levels in the blowtorch she used to weld sculptures, and soot poured out. She began to draw with the torch, moving it across paper and canvas. ‘I finally got the black I wanted and a kind of landscape or “worldscape,” she said.”

Untitled ,1963, soot and aniline dye on muslin, is another beauty, much less overdetermined than some of her other more illustrative and instrumental drawings for sculptures. It would be very interesting to see this work next to one of Myron Stout’s works in the collection, such as Number 3, 1954: on a black ground, a series of ochre and white ovals frame a black center, with one very thin black line cutting through the concentric rings but not penetrating the last white band closest to the center. The ochre and white dye appear on the muslin in such a delicate fashion because of the muslin’s fine weave, and the use of dye rather than pigmented matter is such that the surface approaches the uncanny. The black created by the soot is absolute.

Mind and Matter and these other exhibition and incidental installations of individual works are part of an ongoing initiative among women curators at MoMA to delve deeply into the permanent collection in order to find out what works by women artists they already own and then see how gaps in the collection can be filled through acquisitions, with assistance from the Modern Women’s Fund. Mind and Matter is organized by Alexandra Schwartz, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Drawings, and Sarah Suzuki, The Sue and Eugene Mercy, Jr. Assistant Curator of Prints and Illustrated Books; Lee Bontecou: All Freedom in Every Sense is organized by Veronica Roberts, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture. Performance 7: Mirage by Joan Jonas is organized by Barbara London, Associate Curator, Department of Media and Performance Art; Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography is organized by Roxana Marcoci, Curator; Sarah Meister, Curator; and Eva Respini, Associate Curator, Department of Photography.

The women involved in this ongoing initiative decided not to follow the example of the Centre Pompidou which in the exhibition elles@centrepompidou filled the entire museum with a one-off, blow-out installation of work by all the women artists in their collection. Instead, the group at MoMA is attempting a more gradual, incremental, and infiltrative approach which, in the long-term, may well be potentially more effective at redressing the balance of representation of women artists in the entire museum.

There is a kind of self-effacing anonymity to the whole enterprise that aligns it with Virginia Woolf’s proposition in A Room of One’s Own that “Anonymous was a woman.” But I think it is important to draw attention to the work of the women artists on exhibition due to this initiative and to the women curators whose efforts should be recognized and supported, since I think one can take as a given that their efforts occur in a context of resistance, based on previous histories from all major museums.

In my essay, “Generation 2.5,” in A Decade of Negative Thinking, I go into some detail about the gender distribution of major retrospectives at MoMA since the mid-1980s (the men’s room is very crowded) and I note that in general it has been my experience or at least my supposition based on observation, that most women curators who want to curate a major exhibition of women artists, never mind of feminist artists, are likely to get just one such opportunity in their careers, if their institutions and funders are amenable. If the ongoing MoMA Women’s Project’s incremental, small scale and stealth approach results in their having the opportunity to organize many more, though perhaps often modestly scaled exhibitions, then their strategy is a good one!

I look forward to the conference on Friday, when these issues will be discussed from many practical, professional, and theoretical points of view.