It’s weird, I wanted to write about a moment of inspiration and instigation I felt in front of one of William Kentridge’s films but for the moment Marina has crowded him out. It’s rare that a woman’s ego trumps a man’s, particularly in the context of one-person retrospectives in a major museum. My title therefore was first intended to highlight the battle for attention between two major artists. But, as this blurred picture suggests, that battle has been won.

Marina and William

But Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present is itself a tale of two egos: downstairs, that of the individual living woman whose body you can witness and potentially engage with at some level, and, upstairs, the projected ego of the woman who has hijacked curatorial common sense, whose many incarnations are screaming at you in an unpardonably cacophonous, unedited installation, who has created a kind of Disneyworld of the Spanish Inquisition through her use of re-enactors in stressful situations while rewriting the history of performance art so that she exists sui generis, without any historical context.

I plan to stay downstairs with the living woman but the wall of noise that hit me at the door of the first room in the upstairs show, the trembling naked re-enactors, and the lack of historical contextualization in the wall text will stay with me as well. I will continue to wonder why the museum has not provided visitors with any information about international performance artworks that would seem to be of immediate relevance to this work, from contemporary women performance artists such as Gina Pane and Valie Export, and Action artists such as Herman Nitsch and Rudolf Schwarzkogler. The tableaux vivant re-enactment of Nude with Skeleton (2002-2005) is for me haunted by Frida Kahlo’s The Dream (or the Bed) (1940). Women artists, nudity, and pain are recurring thematics of feminist art as well as personal obsessions of individual performers. It would be useful to offer that context even if Marina denies it.

Frida Kahlo, The Dream or The Bed, 1940

Even before you get up to the level of the spectacle taking place in the square arena marked by a line of the floor, guards, warning signs, and four stands of film lights, the bright white light from the atrium is already beautiful and enticing seen from the lobby below:

Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present, from the lobby MoMA May 2010

The first time I went to see the show, April 29, there was still a table installed between Abramovic and those sitting opposite her. I was with Susan Bee. We have seen many exhibitions together over many years and I always value her insights. We circled the square, surveying Marina from all sides — oops, I’ve lapsed into something that is against the rules of scholarly writing: you do not refer to artists by their first name, you do not talk about what “Pablo” was doing in Guernica, but I’ve noticed that a lot of women artists and art historians, whether they know — Marina — personally or not, are referring to her by her first name, sort as if it was her only name, like Cher or Madonna.

I found some of the visuals distracting, especially Marina’s red ecclesiastical garment, which one friend has compared to one of those snuggies, the blankets with sleeves advertised on TV. Many women viewers are concerned about how Marina pees: one artist is absolutely persuaded that the (I’m told it’s a Prada) dress is designed like an astronaut’ s suit with special receptacle panels and some catherization going on in there, another is as certain that she pees into the chair (if you visualize this in further detail it would mean there’s a big hole cut out of the back of her dress, which somehow I doubt).

Nevertheless as we circled the scene with interest, Susan’s comment, after a short while, that “it’s sort of dignified in a way” echoed my own thoughts: perhaps we had come with a bit of snarky attitude about the hype surrounding the show and were surprised at our response once we were standing there (we did not chose to sit and in any case would never have made the effort to get there early enough or pulled enough strings to score a privileged spot at the head of the list to face Marina).

There is something hypnotically appealing about the whole scene, the lights, the square, the faces of both participants, the strange shift between proximity to and distance from the two seated figures — it may be an optical illusion but you definitely feel closer to the figures and see the details of their faces and skin in better focus from the South side of the square even though the chairs appear to be centered. The hypnotic atmosphere must also emanate from the artist who is presumably present, intent on each viewer — that is after all the premise of the work — yet undoubtedly self-hypnotized.

I’m not sure she is responding to the viewers any more intimately than Queen Elizabeth on a receiving line — if anything, the Queen may feel more duty bound to work a display of connection. Yet Marina’s face has a melting blankness which is quite fascinating and there must inevitably be a mirroring that takes place when two beings face each other for any length of time in silence.

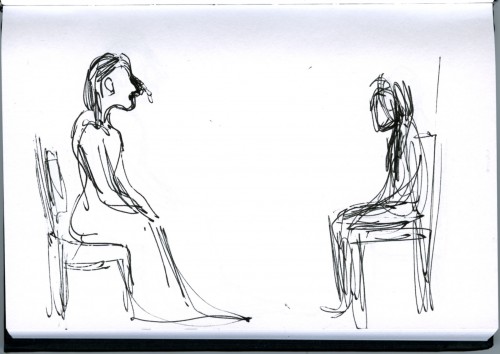

This week the scene was visually reduced: the ecclesiastical garment is white and the table is gone, which exposed both participants to each other and the audience. Since photography is forbidden despite (or because of) the fact that the whole thing is a photo-shoot set, I did a quick sketch of the scene:

Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present, seen from the North side of the atrium MoMA May 6, 2010

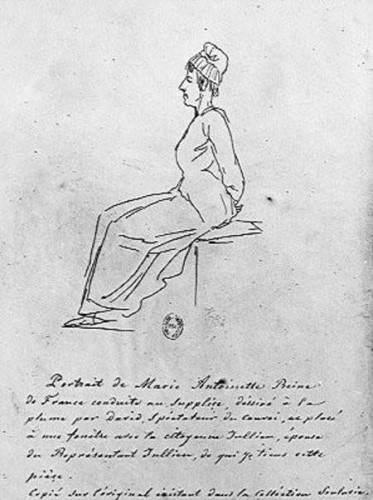

I’m amused that the artist’s effort to control documentation of her work forced me to turn to that old representational technology, drawing. And through the act of drawing, I experienced a strange apprehension of the scene, a perception that I might not have had if I had just held my camera up and waved it in the general direction of the subject. As I drew, I felt that I recognized a familiar form, something about the white dress, the slumping body, the prominent nose:

Jacques-Louis David, sketch of Marie Antoinette on the way to the Guillotine, October 16, 1793

I was not sure of the orientation of Marie-Antoinette’s face in the David drawing until I got home, but meanwhile I walked around the room to draw the scene from the other side.

Mira Schor, sketch of Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present, from the South of the Atrium, MOMA, May 6, 2010

I draw no meaning from this coincidental resemblance between an exhausted looking Marina and a doomed Marie-Antoinette although there is certainly a generous dose of violent martyrdom on view in the work exhibited upstairs! If, despite the self-hagiographic-monarchical-ecclesiastical set-up of The Artist is Present, there is “something dignified” about Marina’s effort not to fall asleep in her chair and keel over, and something eerily pleasant in wandering around a light flooded public square, I don’t feel there is anything either dignified or interestingly desublimated about the spectacle of a woman pinned high on a spotlit wall, balanced on a bicycle seat, her arms held up in a pose of crucifixion, trembling with pain.

Meanwhile in the back room … see my next post about Kentridge and creativity.