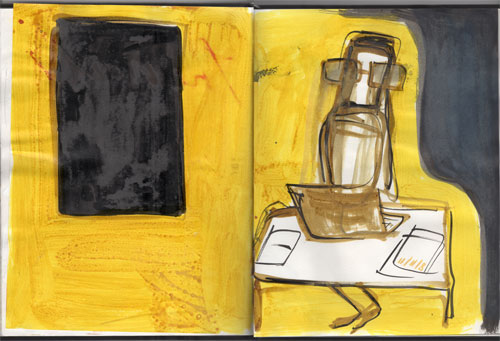

August 3, 1976

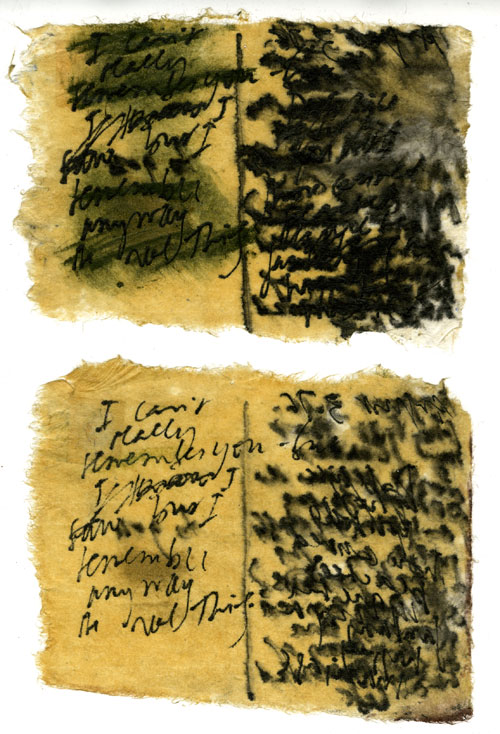

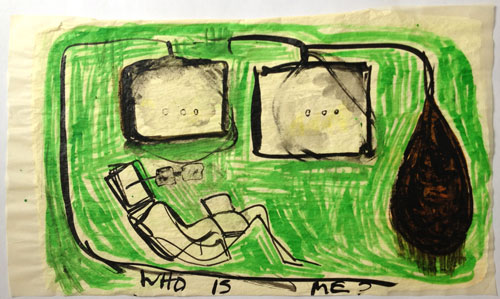

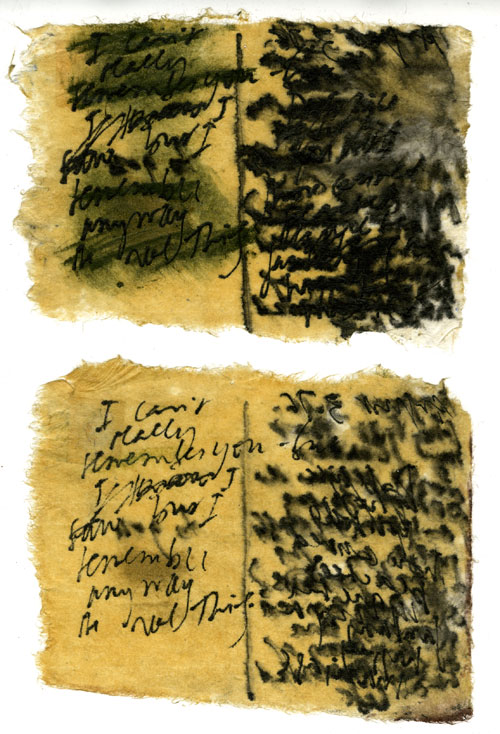

Mira Schor, Postcard: From the Deep Pool of Dreams to Landlocked, August 3, 1976. Ink, dry pigment, medium on rice paper, c. 3 1/2 x 6 in.

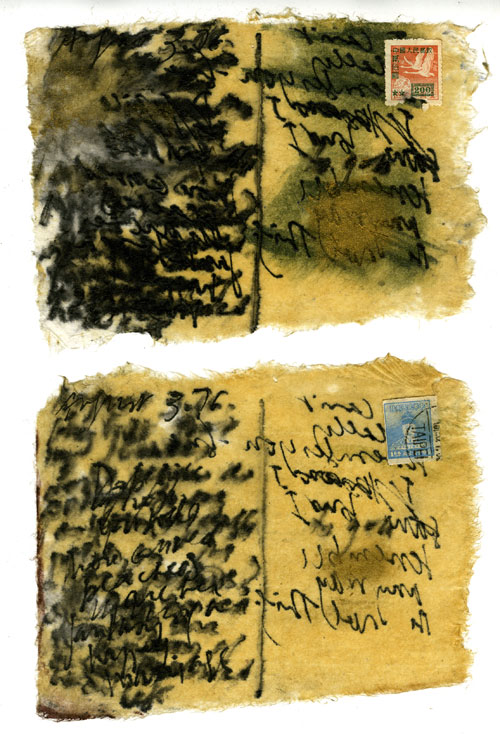

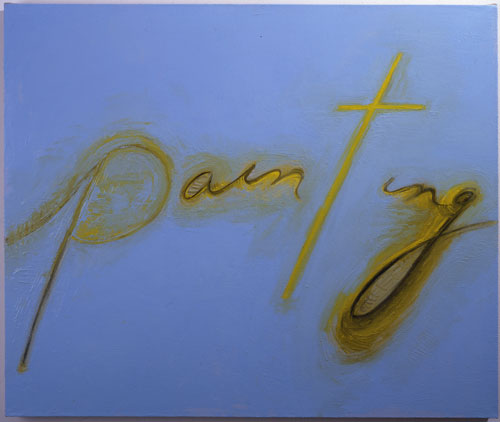

Mira Schor, Two Postcards (side 1), August 3, 1976. Ink, collage, medium on rice paper, c. 4 x 6 in. each

Mira Schor, Two Postcards (side 2), August 3, 1976. Ink, collage, medium on rice paper, c. 4 x 6 in. each

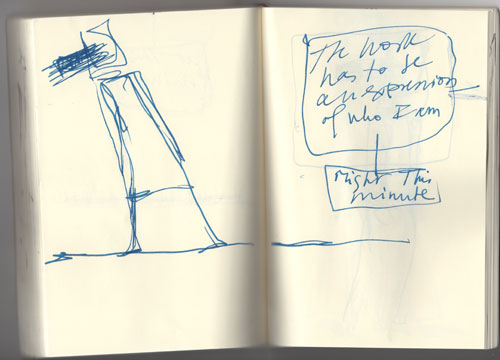

Postcards/blog posts. You mail a postcard, although I did not mail the postcards I made as artworks in 1976-77. You “publish” a blog post and it goes out into the mysteriously infinite internet, including in my case to a number of subscribers who I believe get these posts as emails. The similarity is that they arrive unexpectedly. This series of posts, Day by Day in the Studio–short spontaneously written essays suggested by works done on particular days in the summer over a period of about 40 years, including only those that I have a specifically dated record of on the hard drive I am working on this summer–has received mixed response as best I can tell. I regularly get one or two unsubscribe notices after each post. This is plain rude and unnecessary behavior, people! I subscribe to many blogs and even old fashioned email posts and, top secret, I don’t read all of them every time, I often don’t have time, so I understand that no one else has any more time than I do, and I’m not necessarily interested in all of them, but I have never clicked “unsubscribe,” first, because it would hurt the person’s feelings and, by the way, it’s not anonymous, the unsubscribe notice includes the person’s email address which may contain their whole name or enough of it, and, second, because by scanning these blog posts in even the most cursory manner I do get a basic sense of what various people are thinking about and doing, and sometimes I find something I like or learn from so it is always informative on some level. On the other hand, I have been getting very supportive emails from other artists including from people I do not know in person, but through Facebook and my writing, which I am glad of because I do try to lace my personal reflections with comments of more general interest to other artists.

In one of these emails, William Conger, a Chicago-based painter, wrote asking

I’m very interested in notions of duality on literature and art. This seems to be a central theme in Terry Eagleton’s recent The Event of Literature. Would you care to say why you have frequently chosen to work on both sides of a translucent surface as if the image/content depends on their integrated presentation?

I was grateful to able to address what is an important aspect of how I have often structured works and I warned him I might use my response to him in a later post and indeed here is it.

I think that before any kind of analysis (in the psychoanalytic sense as well as any other) of why I work on both sides of the translucent paper, I owe that process to inheritance. Both my parents worked on both sides of every object they made, jewelry, Judaica, and sculpture, and my father painted on both sides of the pieces of cardboard he painted on–the image on the back was not translucent or functional as in my drawings, but in both cases there is always a sense of discovery and pleasure when you see the reverse side or the interior. In my mother’s work in particular, she recognized the visual power of the back of her works in silver, so that the functional, unintentional forms that helped created the “front” image was just as interesting though often with a darker feeling..if you look at my blog and search for the posts on both their work, Resia Schor and Ilya Schor, you will see examples of what I’m describing. I’m just finishing work on a catalogue for a show this summer here in Provincetown of their sculpture and that aspect of their work is featured in the catalogue.

I also find that as I began to work with rice paper and through experimentation began to work on both sides, then deliberately to work one side to create the other, that the “back” side often had a vigor that sprang from decision made purely instrumentally, thus without self-consciousness, and gradually the “back” became “the front” or no distinction could be made. Although oil painting doesn’t allow for that particular method of production of a surface, I try to remember the freshness that comes from unintentionally.

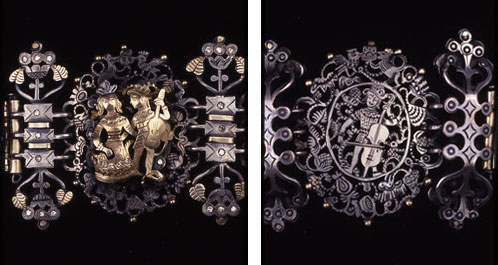

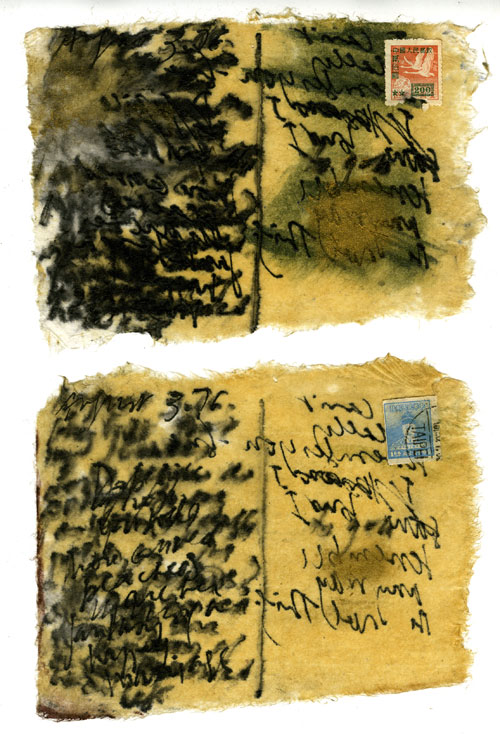

Here are examples of the back and front of works by my parents that will be exhibited in the exhibition Abstract Marriage: Sculpture by Ilya Schor and Resia Schor, opening August 16 at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

Ilya Schor, Angel (back and front), c.1959-60. Brass with brass wire, 26 1/4 x 11 1/2 x 7 in. riveted to a wood base.

Resia Schor, Nike (front and back), 1981. Brass, Plexiglas, gouache on paper, 12 x 12 in.

And here are other examples of how they worked the back and the front of almost every work they made. In the case of my father, the back most often functions as a kind of unconscious of the work, a night for day, or simply provides a surplus of delight, visual pleasure where it would not ordinarily be seen, as in the front and back of a bracelet in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but rarely is it directly instrumental or indexical, unlike the back’s of my mother’s works, as in the pendant below, where the back leaves open to view how the work was made while creating an image as, if not more, interesting than the “front.” (I demonstrate the delightful complexities of my father’s bracelet in my 2003 video on my parents’ work, The Tale of the Goldsmith’s Floor, an illustrated video script appeared in differences in 2003).

Ilya Schor, Bracelet (front and back of a detail), 1958. Silver, gold, diamonds, approximately 6 x 1 1.5 in. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Resia Schor, Pendant. Silver and gold, approximately 4 x 2 1/2 in.

When I began to paint in oil in the early ’80s, the medium presented challenges, many of them of a nature familiar to anyone who has tried to master this medium–how to effectively be either loose or tight, and how to avoid mud, the most feared by-product of first attempts–and some that were particular to how I had previously arrived at an image. For years I worked both sides of rice paper so that several experiences of the creation of the image were visible at the same time in the final layer: dry pigment on the back of the paper pushed color and highlighting through the front without being present as a tactile element, while the dry pigment on the front as tangible as a sculptural element. In oil I had to figure out a way to make these complexities of layering happen as oil painting allows, where most of the layers are covered over and you cannot see through to the beginning of work and the back doesn’t penetrate the front except chemically and through refraction of light through layers of matter of which the viewer is not consciously aware: in oil painting, the under layers do affect the final surface in many ways causing conservatorial stability or havoc, but these layers are mostly hidden to the viewer and thus seem to operate as alchemy–leading to the fascination infrared imaging of paintings holds for us, as we discover what is going on in some of those unseen layers.

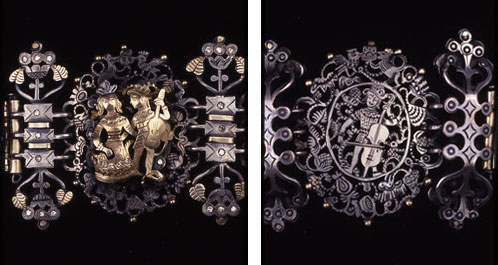

August 3, 2003

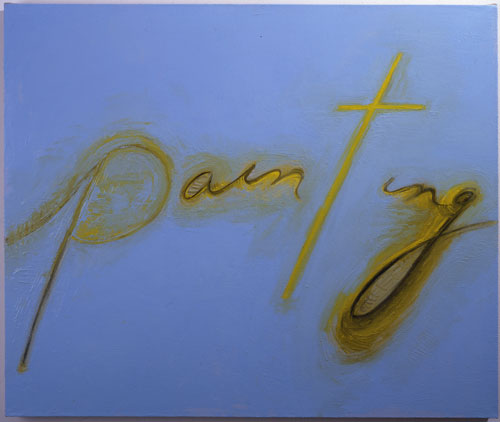

Mira Schor, Painting (yellow on blue), 2003. Oil on linen, 30 x 36 in.

It took a long time to adjust to the way in which the layering of an oil painting goes from a bottom layer (whose back is closed to us by sizing) to the visible final layer which is the painting image, here in a work that represents what it is and what I do, painting, or pain-t-ing as some might read it.

Meanwhile I continue to work on a type of paper which allows me to work front and back though because it is less resilient than rice paper, I mainly put white gesso on the back so that it gives an overall highlight to the work while also offering another, acrylic layer of matter to thicken and strengthen the work.

Mira Schor, Untitled, end July 2012. Ink on tracing paper with gesso on reverse side, c. 18 x 30 in.

While I continue to work both sides of paper, I also appreciate the blunt opacity of oil.

August 3, 2012

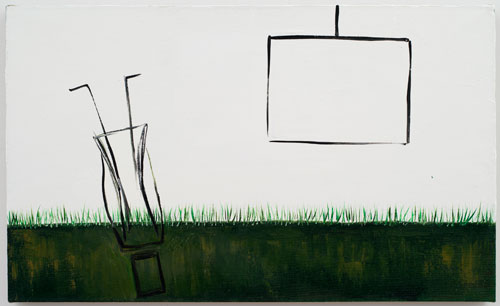

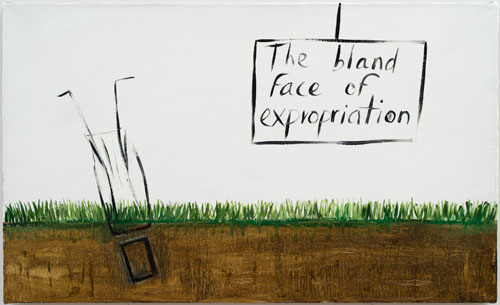

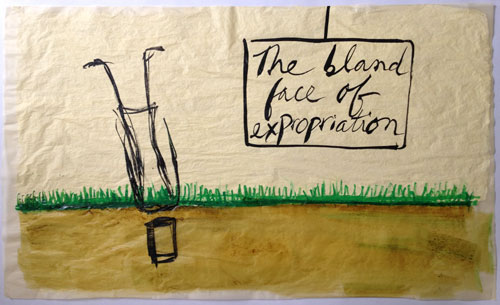

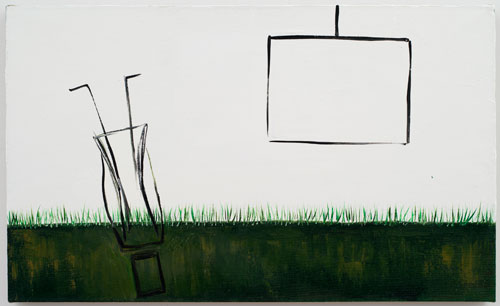

Mira Schor, The Bland Face of Expropriation (II), August 3, 2012. Oil on linen, 18 x 30 in.

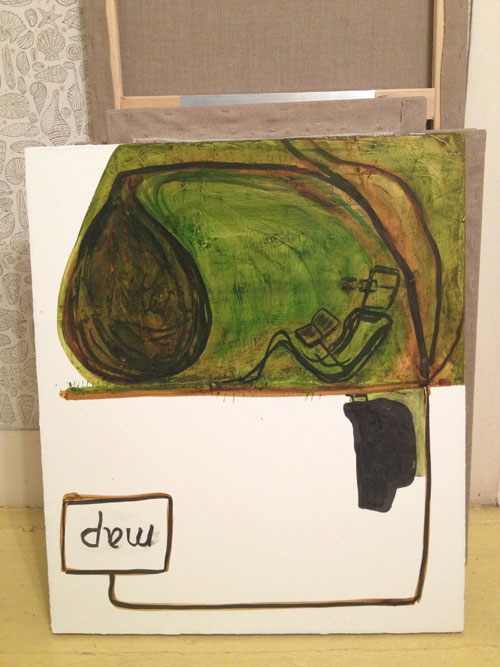

Many recent paintings combine drawing and painting techniques and ethos such that I call them oil-assisted drawings: at best they keep intact the potential for spontaneous line that is more easily achieved in drawing while adding the color and materiality of oil paint, whether it be glaze or a beautiful opaque pigment used straight from the tube onto the canvas, in the case of this painting also finished August 3, 2012, a tube of Old Holland Cobalt Blue Turquoise that I had hanging around the studio since the ’90s. The painting presents two spaces–the garden in a summer’s night, and the classroom in winter, and it suggests a third, the space that is the ground of the whole painting, the flat gesso “wall” I create on linen, so that in the painting the figure in the dream of winter, dreams of an escape, which is back to the ground of painting.

Mira Schor, Fallow Field Series: Last Dream of Summer, August 3, 2012. Oil, ink on gesso on linen, 18 x 30 in.

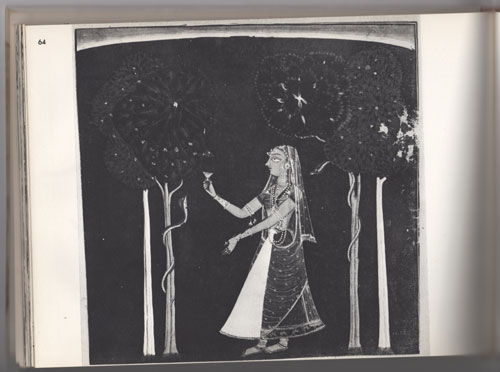

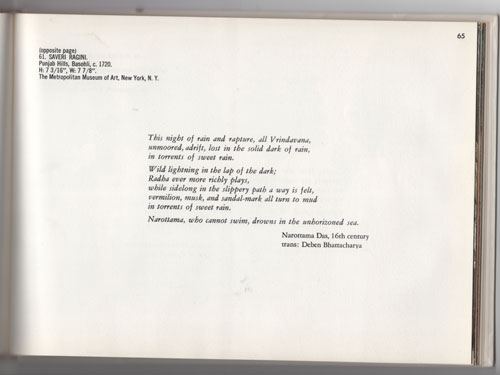

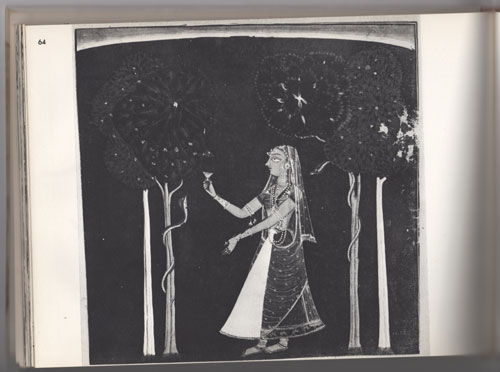

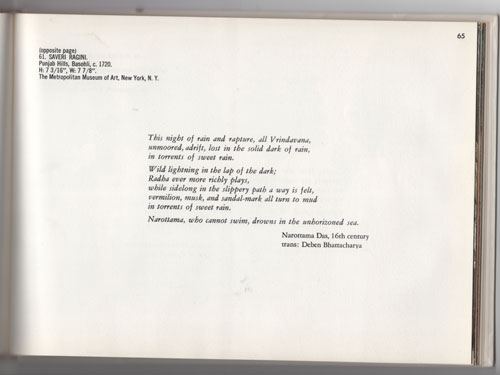

The rapturous and desperate attempt to draw enough strength from the earth to deal with winter in the city trapped in rooms, recalled some important influences and this summer I became taken with the necessity to see and read something again that I had been introduced to at the very beginning of my becoming an artist, a beautiful catalogue on Rajput Painting from a show at Asia House in New York in 1960. The paintings reproduced in this catalogue–small works on paper, combining vivid color, rich narrative, radiant nature, and sometimes language–gave me support at a time when painting still generally had to be large, abstract, oil or acrylic on canvas, with no evident personal or narrative content to speak of. As important as the paintings reproduced in the catalogue were ancient Indian poems accompanying three or four particularly rapturous paintings. A few misremembered words of one of the poems has been like a refrain of a song in my mind this summer, “all rain and Vrindavana.” Googling Vrindavana did not make the remembered line make sense and I wanted to assure myself of my memory so much that I ordered a second copy for my studio here–a hardcover catalogue from 1961 turned out to be available and cheap online– and it arrived today, August 3, 2013.

This night of rain and rapture, all Vrindavana/ unmoored, adrift, lost in the solid dark of rain/ in torrents of sweet rain.

Wild lightning in the lap of the dark;/ Radha ever more richly plays,/ while sidelong in the slippery path a way is felt,/ vermilion, musk, and sandal-mark all turn to mud/ in torrents of sweet rain.

Narrotama, who cannot swim, drowns in the unhorizoned sea.

Narottama Das, 16th Century, trans.: Deben Bhattacharya