I’ve spent the summer with my thoughts trapped inside three caves–the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc cave featured in Werner Herzog‘s Cave of Forgotten Dreams, the cave inside a malachite mine deep in the Ural Mountains featured in a 1946 Russian children’s movie The Stone Flower, and the cave whose entrance lurks in the shadow of Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in the Desert, currently on special display at the Frick Museum in New York.

Is it any wonder that, in a summer when the prospect of a long and deeper recession and of a second American Civil War in which the Tea Party descendants of Jefferson Davis win looms closer and closer (well, so close it’s here), one might want to take refuge in a cave, especially one with art in it? Yet I’m deeply claustrophobic so I must find a way out. This blog post/essay is my process of digging myself out.

* Cave of Forgotten Dreams

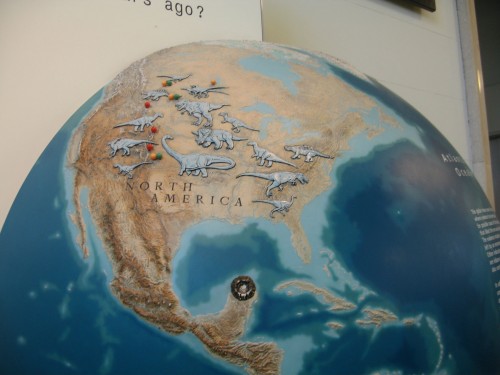

Dinosaur on Central Park West

The son of a friend was about four or five years old and obsessed with dinosaurs, he knew all their names, the usual. I said, you know, creatures like that used to walk the same earth as we do. He looked at me with total incredulity and got right to the point, “Here, in New York City?”

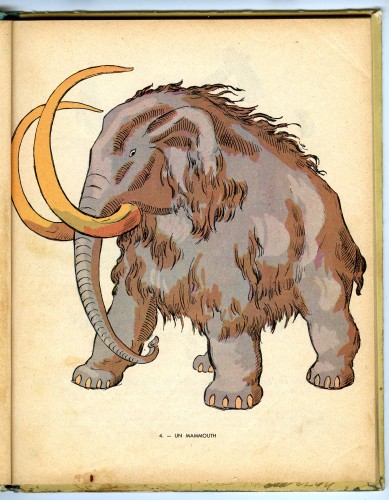

Mammoth, Natural History Museum, NYC

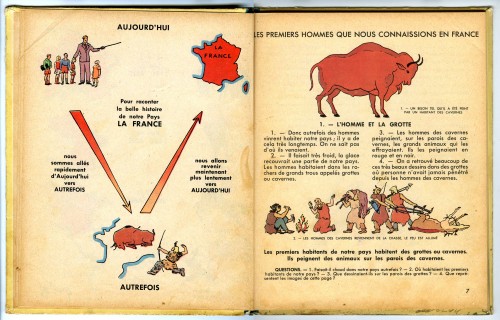

"Un Mammouth," illustration from my second or third grade history book, Petite Histoire de la France, Lycee Francais, mid-1950s

I was never interested in dinosaurs, too snake-like for me. But as a child I was fascinated by the idea that other creatures now extinct had once roamed the earth. The pictures and simple stories in my history book from second or third grade conveyed the wondrous idea that once upon a great but intelligible amount of time past, there had once been Mammoths here. Yet the “here” of my schoolbook was already marked by estrangement: its “here” was France, but I was not French, had never lived in France, had in fact not yet visited France when I read the book. It didn’t occur to me to imagine a single ancestor who might have ever struggled with a Mammoth, though I suppose genealogically speaking it’s possible that my grandfather, a Hasidic folk artist, a sign painter and stone carver in a shtetl in Galicia, may have had deep in his ancestry some fellow in the back of the cave carving a little bison out of a piece of bone, sometime back in 32,000 BC–we all do descend from someone back then, fifteen hundred generations ago, but basically I didn’t think there were any Jewish cavemen!

My little friend’s disbelief and the Mammoth in my history book returned to my mind seeing the fantastical narrative device used by Herzog near the end of Cave of Forgotten Dreams, when he pulls the camera away from the rock face protecting the Chauvet cave in the Ardèche region of France and shows us a nearby nuclear power plant (I looked it up, there is one) whose hot steam emissions are said to fuel a hi-tech glass-enclosed hothouse in which radioactive albino crocodiles in a pool seem to be prepared to restart the process of evolution in case there’s a nuclear accident and we have to start all over again. Like the image that had crossed the mind of my little friend, of dinosaurs walking down the street in front of his mother’s apartment on Fifth Avenue, Herzog’s fiction (or science fiction–as he explained to Stephen Colbert: “I want the audience with me with wild fantasies”) points to the jarring and slightly ridiculous effect of considering the deep past’s uncanny co-existence with our present.

My response to the Herzog movie has centered on what may seem like the “wrong” thing: what really struck me and has stayed in my mind are not the cave paintings themselves, amazing though they are, according to any criteria, be it expressive verisimilitude, mystery of original purpose, nearly unfathomable age, and difficulty of location and surface, but Herzog’s use of 3D which serves to enhance what is from my point of view the central thematic of the movie, which is that estrangement is intrinsic to wonderment.

The principal claim for Herzog’s use of 3D is that it would give the viewer a better approximation of the effect of the cave paintings’ adaptation to the curved walls. Herzog says he wanted to “intensify” the experience for the movie viewer. But my most powerful impression was of the way that the 3D amplified the separation between figure and ground, creating a flattening effect that does not feel like the way that we see. I mean, yes, if I look at you, I don’t really see the room around you in focus, but you are not a flat cutout doll completely separate from a distant ground, there is a much greater impression of visual integration. But in the Herzog movie human beings were sharply separate from the space they occupied, whether in the scenes filmed in the cave itself as well as when they were filmed in the landscape.

At the end of the movie, the camera draws further and further away from people exploring the landscape around the cave. The human figures, flattened, outlined, and distinct from the stone ground they stand on, become smaller and smaller paper cutout dolls, human beings as not even ants but toys for an all-seeing deity or creative force (which here is Herzog or whoever he is a stand-in for). The cave paintings are almost just an intermediary focus for the true subject of the film which the stupendous difference between the scale of human effort, however valiant, and the incomprehensibly greater scale of archeological time.

Herzog’s storyteller’s voice and foreign accent in English also cast the spell of the folktale over the documentary format. And when one of his guides in the cave calls for silence so that perhaps the visitors will hear the sound of their own heart beat in the deep stillness of the deepest recess of the cave, for a second you think, yes, let me just look and listen to my own heartbeat, maybe I will really feel I am there, but instead of that silence and the dream of private experience, cue the Wagnerian chorus! Again, the “documentary” filmmaker seems to insist on the absolute absurdity of actually thinking that you could experience the cave and its art in a pure fashion. As Stephen Colbert says, “Let me ask you a question here: You making any of this stuff up?” Herzog has gone out of his way to make sure that is a fair question.

In fact ever since Paleolithic cave paintings began to be rediscovered in the late 19th and the 20th century there have been people who thought they were fake. People continue to think this or pretend to for their own purposes . I’m not taking the position held by some that these are 19th Century fakes but Herzog’s propensity for artistry/fakery puts the whole enterprise in question. And anyway contemporary perception is so influenced by simulacral thinking that the gleaming nearly flesh colored crystalline deposits that encase bear skulls and covers large areas of the cave floor in a shiny flat layer of hard shiny pink glop looks a little too much like the cheesy sets of the first Star Trek series. In fact caves are visited with regularity in all variants of Star Trek, for one thing because the possibility of beaming people through barriers of stone holds a particular fascination.

In one episode, The Devil in the Dark (1967), miners of an important mineral element found in tunnels within solid rock under a planet’s surface are being killed by an unknown force (with moving multicultural tolerance plot twist of course). The cave chambers have been mapped, much as they are in another fascinating detail of Herzog’s film, the laser imaging of the interior shape of the Chauvet Cave with its network of irregular shaped chambers.

Map of the Chauvet cave chambers found @http://www.donsmaps.com/chauvetcave.html

Detail of computer visualization of the interior conformation of the Chauvet cave chambers

One could find the Star Trek narratives to be memorable and powerful at the same time as it was pretty obvious that the rocks were made of spray-painted Styrofoam and bubble-wrap seemed to be the principal building block of the universe.

Bear Skull in the Chauvet Cave

"The Injured Horta," The Devil in the Dark, Star Trek, 1967

Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave

That does not diminish the potential for magic because at the same time even just the idea of the cave is very powerful in a somatic sense: I could barely breathe during much of the Herzog film, a sensation that was only lifted when, towards the end, as the camera makes a repeat sweep through the deepest cavern, it is revealed that when the cave paintings were made and for thousands of years thereafter the cave chambers were more open to the outer landscape, giving freer access to men and to the bears who left their claw marks on the painted walls. It was only after I could visualize an opening to the outside world that I could breathe better and experience the thrill of a group of lunging beasts.

Horses, Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc cave painting

*

You may once have had experiences of wonderment and delight, perhaps most uniquely in childhood, in your imagination, reading a book, hearing a story, or seeing something of incomparable beauty. You’d think being an artist would give you continued access to such experiences but for the most part life as a professional artist is at best a negotiation among the constantly changing realities of contemporary art, the limitations of one’s own abilities, and some internal core ability to still experience such wonderment when it presents itself, despite competitiveness, jealousy, and the infrequency of such experiences. Basically we once experienced wonderment and now we do the best we can. So when we do on rare occasions experience wonderment or delight, it is notable, and for a moment we may return to the prelapsarian intensity, awe, and joy first experienced in childhood and which is part of the secret fuel for a lifetime of art practice.

*The Stone Flower

Sometime in the 1950s when I was a child my mother took me to see an old Russian movie playing in a second run movie house someplace near Carnegie Hall. This experience remained in my mind as an intense visual experience, colorful, rich in detail, and one somehow tinged with the obscure and exotic. Distinct images from the movie remained in my mind as well as the sense of how it was to actually be in the theater watching it. I can nearly feel it to this day, a haptic and visual sense of being there and of seeing myself seeing it, but the movie itself disappeared from my cultural scope. I wasn’t sure of its title and I forgot the story. I never asked my mother about it and I never came across a revival or even a reference to it.

My mother took me to see old movies often, usually Laurel & Hardy or Charlie Chaplin, at MoMA, so being taken to see an old movie was not a unique experience, and the foreign language, Russian, was one which I did not exactly understand but whose soft sweet intonations I was familiar with from hearing it spoken by family friends, yet something about the circumstance of seeing this movie seems to have stood out for me as out of the ordinary, but perhaps it is just that I saw something beautiful on a day when I was just primed to receive it.

It should be said that where I remember seeing it was a kind of New York version of a dark cave or grotto, this old movie theater someplace near Carnegie Hall but which was not the Carnegie Hall Cinema. That was part of the exotic, this was not someplace we ever had been to see a movie before or went to after. [I did find a reference in the New York Times to the movie being shown at the New York Historical Society in March 1955, that is, three blocks from our apartment, but I am pretty sure that wasn’t the time or place, and since you can only search the Times archive for articles and editorial content, not for movie ads, unless another madeleine dipped in espresso fills in the details of my memory, I will eventually have to track through two or three years worth of microfiche at the New York Public Library in the hopes of recuperating the date and location.*See postscript below]

This winter a strong, palpable remembrance of the movie resurfaced during a studio visit, triggered by a student’s use of mass-produced glass flower vases assembled in some measure to try to summon up a sense of the wondrous in the intangibility of air contained within glass, I think. The movie’s title, which had always been at the tip of my mind, came to me, or at least enough to have the confidence to Google what I thought it might be– The Stone Flower. I first found a variety of references, including to the Serge Prokofieff opera The Tale of the Stone Flower, based on a P. Bazhov’s fairy tale “The Malachite Box,” a 19th century folk tale, and then reference to the film itself. I asked a young Russian painter, Tatiana Istomina if she remembered such a film from her childhood and she then found the whole film for me on YouTube. There in 8 parts with English subtitles was the film I remembered, and my memory had been exact as to both the exoticism and the magical beauty.

The director, Aleksandr Putshko, is sometimes referred to as the “Soviet Walt Disney,” and there are some similarities to Disney in the delightful representations of nature and even in the bad guys: it turns out that Soviet films and Disney films share the same type of villains–the local rich person and his brutal overseer. But The Stone Flower is more like its near contemporary, the great British ballet movie The Red Shoes (1948); it shares with that film not just rich vibrant color and a sense of set design that seems influenced by the stage design style of the Bolshoi Ballet and Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. Also and more importantly it shares with The Red Shoes the theme of the artist as torn between an all-consuming search for perfection in art practice and what The Red Shoes’ pivotal character of the ballet impresario, Boris Lermontov, contemptuously refers to as “the doubtful comforts of human love.” Because you see, and here is what I think is so fascinating about this particular aesthetic memory, I had remembered everything about The Stone Flower except perhaps the most salient reason the movie had such an impact on me: it is about being an artist, not just about being naturally gifted and skilled but more importantly about the sacrifices that the artist makes in the obsessive search for perfection.

The film is framed by a narrative device: peasant children gather around the campfire of an old man and clamor for him to tell them a story, which then unfolds in a once upon a time era, not as deep in the past as the Chauvet cave painters, but in the equally lost past of 19th century peasant life in Czarist Russia. In the story he tells, which he carefully distinguishes for his young audience as not a fairy tale, which is for little children. but, rather, “folklore and narrative,” the young hero Danila neglects his duties guarding cattle while he is enraptured by the beauty of a wildflower in the forest. He is observed in this early sign of artistry by a sorceress disguised as a salamander wearing a little tiara: this is the Mistress of Copper Mountain. [This scene comes in at about 7 minutes into the film).

In that first scene in the forest the basic fakery of cinema comes through in a very intense way, similar to the richly detailed illustrations of children’s books in the 19th and early 20th century: there is a very strong naturalism, in the use of real trees, vegetation, and real animals from squirrels to a small herd of cows, yet the atmosphere is intensified by deep color and chiaroscuro and the suggestion of compressed space, the space of the cinema set, a kind of cave in itself. I think that the combination of naturalism, even realism, with artifice is part of what made the film such an intense and memorable experience. If anything, in fact I think definitively, the analogue nature of the sets and the special effects add to the wonder.

But please remember, a film viewed on YouTube cannot replicate the experience of seeing a film lauded for its color–it received the Grand Jury Prize for Best Color at the Cannes International Film Festival in 1946–filling the screen of a darkened movie theater.

When Danila’s absorption in the patterns of the flower causes him to neglect the cattle, he is to be beaten but an old stone carver defends him to the cruel overseer and so is beaten for his troubles. But then the boy is given over to the stone carver as a ward and student. Danila grows into a handsome and supremely gifted stone carver but he is dissatisfied with his most ambitious achievement, a flower-shaped malachite vase. He wants “to gather all the beauty of a living flower and show it in the stone that it would never wither.”

The second part of the following clip takes place in a barely lit peasant’s wood cottage (a type of cave) where Danila and a number of old stone carvers consider the nature of artmaking. Danila hears the tale of the Stone Flower: “The Stone Flower? What’s it like?” “It’s to for us to see it. One who sees it will forget all about earthly life.” I’ve included this clip because now this interests me, this narrative discussion about art. I would wager that even though perhaps as a child I found the scene a bit talky compared to the forest and cave scenes, I took its meaning to heart, a warning about the danger of forgetting about earthly life if you devote yourself to art.

Danila feels he must see this stone flower and to do so he must go to the cave which formed the center of my childhood memory–in the last section of the film, where a happy ending does nothing to convince any artist of the relative value of “the doubtful comforts of human love” to one who is absorbed in the search for perfection at the heart of The Stone Flower.. Ah, now readers, here the rub: since I first saw the entire film on YouTube in a series of 8 clips, the 2 clips that take place within the cave have been removed for copyright infringement by the production company Mosfilm which has the entire film up on its own YouTube channel where you can watch the whole thing, and with subtitles if you click on “cc”.

What’s perceivable as fake can also be deeply convincing emotionally and powerful aesthetically, the “fake” is a manner of estrangement that can lead to wonder, and the idea of the cave being a magical creative site.

*

The third cave is one that you cannot enter, in fact you can barely see it, it’s a dark crevice of an entrance into a stone mountain in Giovanni Bellini’s 1480 painting St. Francis in the Desert currently on special view at the Frick Museum...to be continued in my next post, that will complete this essay, which as much as anything I’ve written is true to the meanings of essay as an attempt, a trial, an endeavor, a feeling one’s way out of a cave of thoughts.

* Postscript: my friend Mimi Gross filled in the memory in an email from August 3, 2011:

I have the exact I mean EXACTLY the same experience about the “Stone Flower” remaining in my memory seen at the Guild Theater (the one you couldn’t remember) where I also saw Citizen Kane for the first time, those early teen age memories / and you were even younger. The same fantasy that never went away, of the sets of the cave of the glowing flower..and will watch the youtubes at a perfect moment since the memory is so delicate. More than Twenty years ago, walking in the snow in Central Park at night, with a Russian film historian, [he] told me all the details of the film, and that it was very well known (no one knew what I was talking about until then) and then, about ten years ago, I noticed it was playing one night only, maybe Walter Reader, and sent two students who happened to be at my house as I was unable to go and they had…the same reactions so many years later.

The Guild Theater was located at 33 West Fiftieth Street.